Intubating (not in the SRU)

/lo-gis-tics: “the things the must be done to plan and organize a complicated activity or event that involves many people”

“Amateurs talk tactics, professionals study logistics” - General Omar Bradley

Logistics are pretty much everything. A focus on logistics is what helps UPS deliver 500,000,000 during the holiday season. A focus on logistics is what helped the Allies win World War II. But logistics doesn’t just happen on the global, macroscopic scale. Logistics plays a role in every procedure we do in the ED and in the prehospital environment. If you only focus on learning the mechanics of physically performing a procedure, you are neglecting crucial steps that will help ensure your success. In this our latest podcast in the Air Care and Mobile Care Online Flight MD Orientation, Dr. Steuerwald and Dr Hill discuss some of the complicating factors for prehospital airways, focusing on both some of the logistical issues that come into play and some of the mechanical/physical considerations.

Logistics

For the most part, we'll let the podcast cover the logistics of intubating in the field. But, I will preface it with this: Intubation is NOT a procedure that one single provider performs. Physically passing an ET tube through the vocal cords is only one small step in the complicated series of actions aimed at maintaining oxygenation and protecting the patient's airway. The logistics of making that happen in the back of the helicopter or in the back of an EMS truck are markedly different than they are when you perform that procedure in the SRU.

Mechanical/Physical Considerations

Direct Laryngoscopy is just that. It is you trying to get a DIRECT view of the larynx or glottic opening to the larynx so you can pass an endotracheal tube successfully. Whether you are a 3-axis person (I am) or a 2-curve person, all this means is you need to remove the visual obstructions that block your view of the larynx. You do this by positioning yourself and the patient in an optimal position that aligns your line of site with the glottic opening. In the ED, this is a (relatively) easy proposition. Raise or lower the bed. Put a ramp behind the patient to align the external auditory canal with the sternal notch. Maybe extend the neck just a bit. Use a little external laryngeal manipulation and bada-bing-bada-boom you get a view of the glottic opening. In the back of the helicopter or in the back of the EMS truck, it’s not quite that simple.

Though these pics are taken in our older BK 117, the common theme of both the BK and most captain’s chairs in EMS trucks is that you are much higher than you want to be in relation to your patient (and the taller you are, the worse it is). The relationship of the stretcher to the chair in the EC-145 is a little better, making this a little easier physically, but it still not the ideal. There are many ways to overcome this and to better align the axes of the patient’s airway with your line of sight. In general, it requires you to sit in the gap between the doc chair and the patient stretcher.

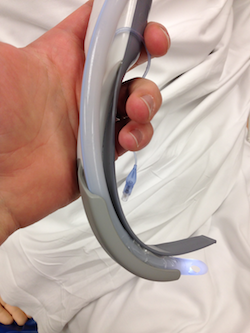

Although, if you wanted to, you could just reach for the King Vision…

As a bonus, here’s Dr. Steuerwald tomahawking the sim head (a viable though likely unnecessary move in the back of the helicopter).

How About Some Data on Intubating in the Field?

Basically the evidence says HEMS programs are pretty darn good at intubating in the field, in the helicopter, on the ground, in the air, or wherever else you would want them to intubate a patient.

Here's a brief rundown of 2 of the major papers on the topic:

Thomas SH, Harrison T, Wedel SK.

Flight crew airway management in four settings: A six-year review. Prehospital Emergency Care 1999;3:310-5.

Retrospective analysis of intubating data from Boston Med Flight (BK-117 and Dauphin) looking at 722 patients intubated in the field

In helicopter - 95.5% success rate, (246 patients), 58 patients required multiple attempts

On scene - 95.7% success rate (117 patients), 24 patients required multiple attempts

In squad truck - 99% success rate (198 patients), 39 patients required multiple attempts

At hospital - 97.2% success rate (143 patients), 24 patients required multiple attempts

McIntosh SE, Swanson ER, McKeone A, Barton ED.

Location of airway management in air medical transport. Prehospital Emergency Care 2008;12:438-42.

Retrospective analysis of intubations from 1995-2007 in Utah (AirMed) with a total of 939 "airway encounters"

Overall success rate of 96% success rate

At referring hospital - 98.7% success rate

On scene - 94.9% success rate

In flight 89.6% success rate (22% of these were performed in a fixed wing aircraft)

References

Ng, Serena. The Last Christmas Present: Lots of Trash The End of the Year is Peak Trash Season, Helped Along by Holiday Gifts and Online Gift Deliveries. Wall Street Journal Online. published Dec 25, 2013 8:07 PM. Accessed 4/18/14.

Overy, R. World War Two: How the Allies Won. BBC Online. Last updated 2/17/2011. Accessed 4/18/14.

Three Axis Alignment versus Two Curve Theory. Life in the Fast Lane. Accessed 4/18/14

Thomas SH, Harrison T, Wedel SK. Flight crew airway management in four settings: A six-year review. Prehospital Emergency Care 1999;3:310-5.

McIntosh SE, Swanson ER, McKeone A, Barton ED. Location of airway management in air medical transport. Prehospital Emergency Care 2008;12:438-42.