Air Care Series: Balloon Tamponade of Variceal Hemorrhage

/Case

Air Care 2 is dispatched at 3 am to a rural community hospital for transport of a 56-year-old male with an upper GI bleed. He has a history of liver cirrhosis by report. On arrival to the OSH ED the patient is found intubated with significant bleeding around the endotracheal tube. He had a blood pressure of 60/30, and heart rate of 130. On exam, the patient has multiple stigmata of liver cirrhosis, with palpable but faint central pulses.

You are concerned that this patient is in hemorrhagic shock from a variceal upper GI hemorrhage. The patient is not stable for transport in his moribund state and needs additional resuscitation. You and your flight nurse continue transfusion of PRBCs and plasma through a large bore IV, but he has failed to respond to several rounds of balanced product resuscitation. What is your next priority before transport?

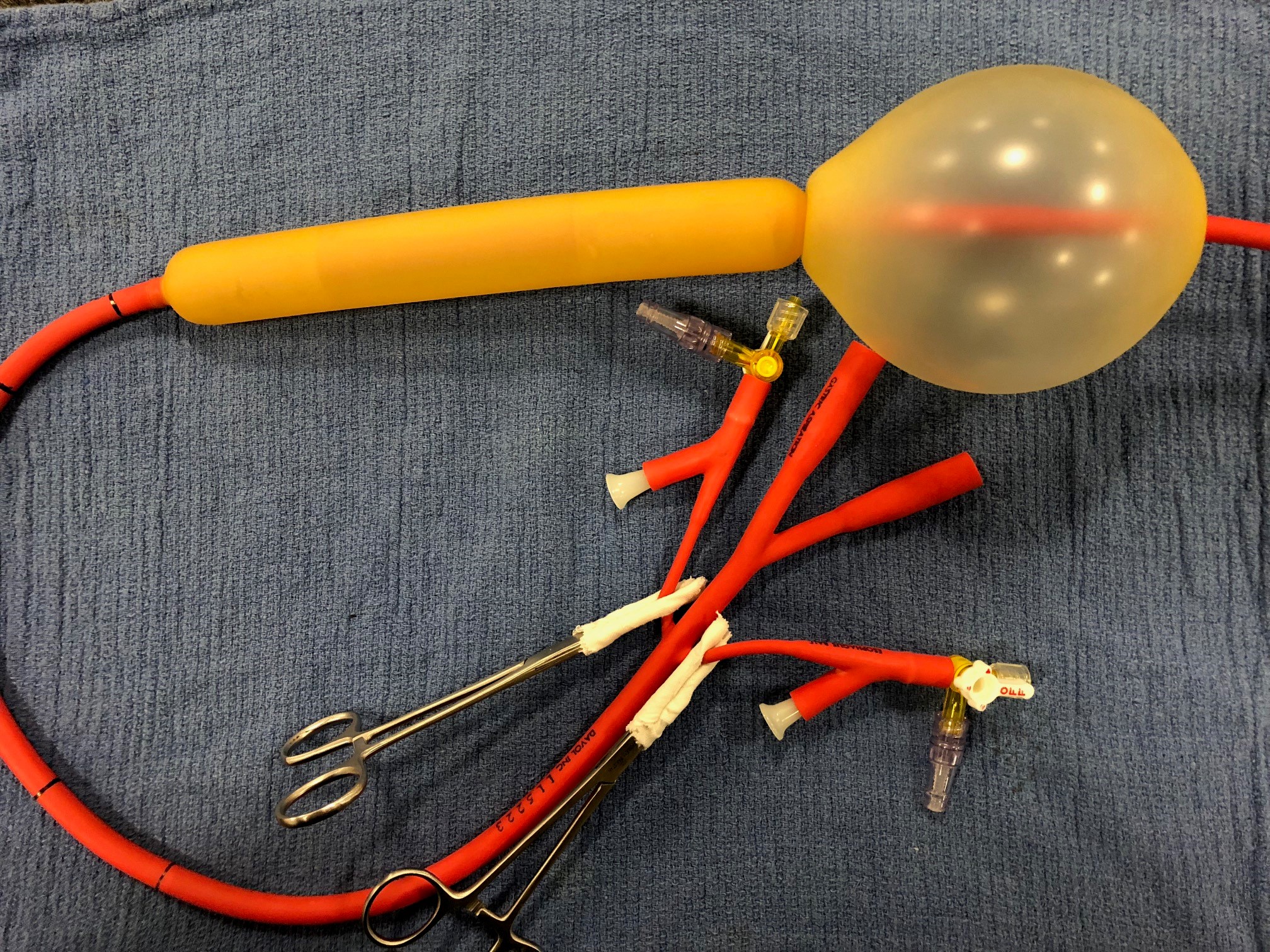

picture 1: Minnesota tube ports Labeled

Balloon Tamponade:

Balloon tamponade is an effective way to achieve temporary hemostasis from bleeding esophagogastric varices. Due to potential for morbid complications it is reserved for unstable patients and is only a bridge to definitive treatment (EGD).

Picture 2: Minnesota tube with inflation adaptors preassembled

Three balloons exist for this purpose:

Sengstaken-Blakemore tube

250 cc gastric balloon AND esophageal balloon

Single gastric aspiration port

Minnesota tube

500 cc gastric balloon AND esophageal balloon

Gastric aspiration port AND esophageal aspiration port

Linton-Nachlas tube

600 cc gastric balloon

Single gastric aspiration port

University of Cincinnati’s Emergency Department and Air Care are equipped with the Minnesota tube. In this post we will go over the placement of the Minnesota tube specifically.

Picture 3: IV caps on three way stop cocks in minnesota tube balloon inflation ports

Picture 4: Inflate 50 mL of air into gastric balloon

Picture 5: Inflate gastric balloon fully to a total of 500 mL, clamp balloon port

Placement of a Minnesota Tube:

Picture 6: Aspirate from the esophageal aspiration port

Picture 7: Using Cufflator inflate the esophageal balloon to 30 mmHg

Picture 8: Inflated minnesota Tube

Indications *

Confirmed or suspected variceal upper GI bleed (gastric or esophageal)

AND

Life threatening hemorrhagic shock as evidenced by:

Shock index > 1.3

Significant pressor requirement despite blood product administration

Greater than 8 units of blood products given in 2 hours

Worsening hemodynamic instability and imminent cardiac arrest

Contraindications

Previous gastric bypass due to risk of stomach rupture with gastric balloon inflation

Equipment

Minnesota tube

Hollister ETT holder

Cufflator

60 mL luer lock syringe

60 mL catheter tip syringe

IV caps x2

Three way stop cocks x2

Kelly clamps protected with tape x2

Minnesota Tube Adapter Preparation

Minnesota tube should have inflation adaptors preassembled (Picture 2).

Connect IV caps to three way stop cocks

Connect stop cocks to the balloon inflation ports leaving the balloon inflation side ports occluded with white plastic funnel pieces (Picture 3).

Other methods exist for managing the balloon ports, see appendix 1 below

Minnesota Tube Placement

Obtain equipment listed above

Test balloons, inflate underwater to ensure no leaks, fully deflate

Patient should be intubated prior to tube placement, preferably with rocuronium to assist with passage of tube

Insert Minnesota tube like an OG tube to 50 cm

A laryngoscope and McGill forceps may assist with placement

Consider the Eschmann Stylet (aka “Bougie”) assisted method as described in appendix 2 below (7)

Inflate 50 mL of air into gastric balloon (Picture 4)

Confirm gastric balloon is below diaphragm on XR

Gastric Hemorrhage Management

Inflate gastric balloon fully to a total of 500 mL, clamp balloon port (Picture 5)

Retract tube gently until hold up is felt (usually ~40 cm)

Secure tube with Hollister ETT holder under 1-2 lbs. of tension (5,6)

Same Hollister is used for both ETT and Minnesota tube; an additional tube clamp is placed in series next to the ETT clamp (Picture 9).

Other methods exist for securing the Minnesota tube including kerlix tied to saline bags over IV poles, and the football helmet method, see appendix 3 below.

Esophageal Hemorrhage Management

Aspirate from the esophageal aspiration port (Picture 6)

If blood return, then inflate esophageal balloon to 30 m Hg using cufflator (pressure may vary slightly with ventilator cycles, Picture 7)

Re-aspirate and if continued bleeding then inflate to 45 mmHg, clamp balloon port (Picture 8)

Picture 9: One Hollister is used for both ETT and Minnesota tube; an additional tube clamp is placed in series next to the ETT clamp.

*The decision to place a balloon tamponade device is fundamentally based on gestalt and an individual provider’s risk vs benefits assessment. This is a decision that cannot be protocolized, as the decision will vary based on unique patient characteristics and the clinical scenario. The below indications are intended to serve a guidelines that may help one make this decision.

**In general pressors are not a great choice for treatment of hemorrhagic shock and may worsen the bleeding, however upper GI bleeds can have a mixed shock picture. Consider that concurrent distributive shock from SBP/sepsis or vasoplegia from hypocalcemia, if massively transfused, may be contributing as well.

***Chosen due to highest mortality in traumatic hemorrhagic shock (13)

Assessing a tube placed by another provider:

For tubes placed prior to your arrival

Identify tube type (see section 1 above)

MANDATORY recent CXR should be obtained to confirm appropriate placement

MANDATORY cuff pressure on esophageal balloon should be checked

If tube is identified to be incorrectly placed then it should be corrected

Tube should be secured with Hollister ETT holder for transport

Aspirate all blood from the gastric aspiration port, clamp port

Example Radiographs of Minnesota Tubes:

Example 1: This Minnesota tube is in correct position but incorrectly inflated. The gastric balloon is only inflated with 150 cc of air (should have 500 cc), and the esophageal balloon is dangerously overinflated, with a pressure that was undetectably high at > 120 mmHg (normal 30 – 45 mmHg).

a.) Example 2: The same patient from ex 1 after balloons were corrected. Notice the gastric balloon is now fully inflated and the esophageal balloon is much less prominent when inflated to a pressure of 45 mmHg.

b.) Example 3: This is a correctly placed tube with gastric balloon inflated but esophageal balloon deflated (patient had no evidence of esophageal bleeding).

Monitoring:

Balloon may be left in place 24 to 48 hours

Deflate balloon every 12 hours to recheck for bleeding

Esophageal balloon pressure should gradually be reduced to 25 mmHg

If bleeding restarts increase by 5 mmHg until controlled

Complications:

Esophageal rupture

Occurs as result of inadvertent inflation of the gastric balloon in the esophagus, risk may be mitigated by pre-inflation CXR. Inexperience of staff is the factor most associated with complications (1,3,4). Therefore, consider rehearsing device placement regularly to prevent skill degradation.

Esophageal/gastric pressure ulceration and necrosis

Occurs as a result of too much gastric balloon tension or esophageal balloon pressure. May be mitigated by periodic deflation and reduction in esophageal pressures during subsequent ICU course.

Critical Upper GI Bleed Management Tips:

Get large bore access with a shorter, wider catheter: consider 14G, trauma catheter, or Cordis/MAC introducer

Give TXA -- physiologically this makes sense and there is some data suggesting benefit, but more definitive literature should be published soon (11, 12)

Continue octreotide if feasible, no mortality benefit but decrease transfusion requirements modestly (9)

Aggressively replete calcium as blood resuscitation (citrate-containing) chelates calcium and can cause a superimposed shock from relative hypocalcemia

PPI drips are equivalent to bolus dosing, so these can be stopped for transport if bolus given (8)

Ensure prophylactic ceftriaxone given for variceal bleeds due to high rates of concurrent SBP, NNT = 22 for mortality (10)

Appendix:

Additional balloon port adapter methods

Tube clamping apparatus if no Cufflator available

This method is used if no Cufflator is available to inflate the esophageal balloon. A second three way stop cock in series is needed on the esophageal balloon port so that a manometer can be attached to measure pressures as air is injected through the first stop cock.

Supplies

Three way stop cocks x3

IV cap x1

IV extension tubing x1

Female Leur Lock Connector x2

Fully assembled apparatus

Kelly clamps with tape

Supplies

Catheter tipped syringe

Kelly clamps x2

Using a catheter tipped syringe inflate the balloons directly and clamp with Kelly’s between air injections. Apply silk tape to ends of kelly’s to prevent damage to tube. This method is simple but is most time and labor intensive.

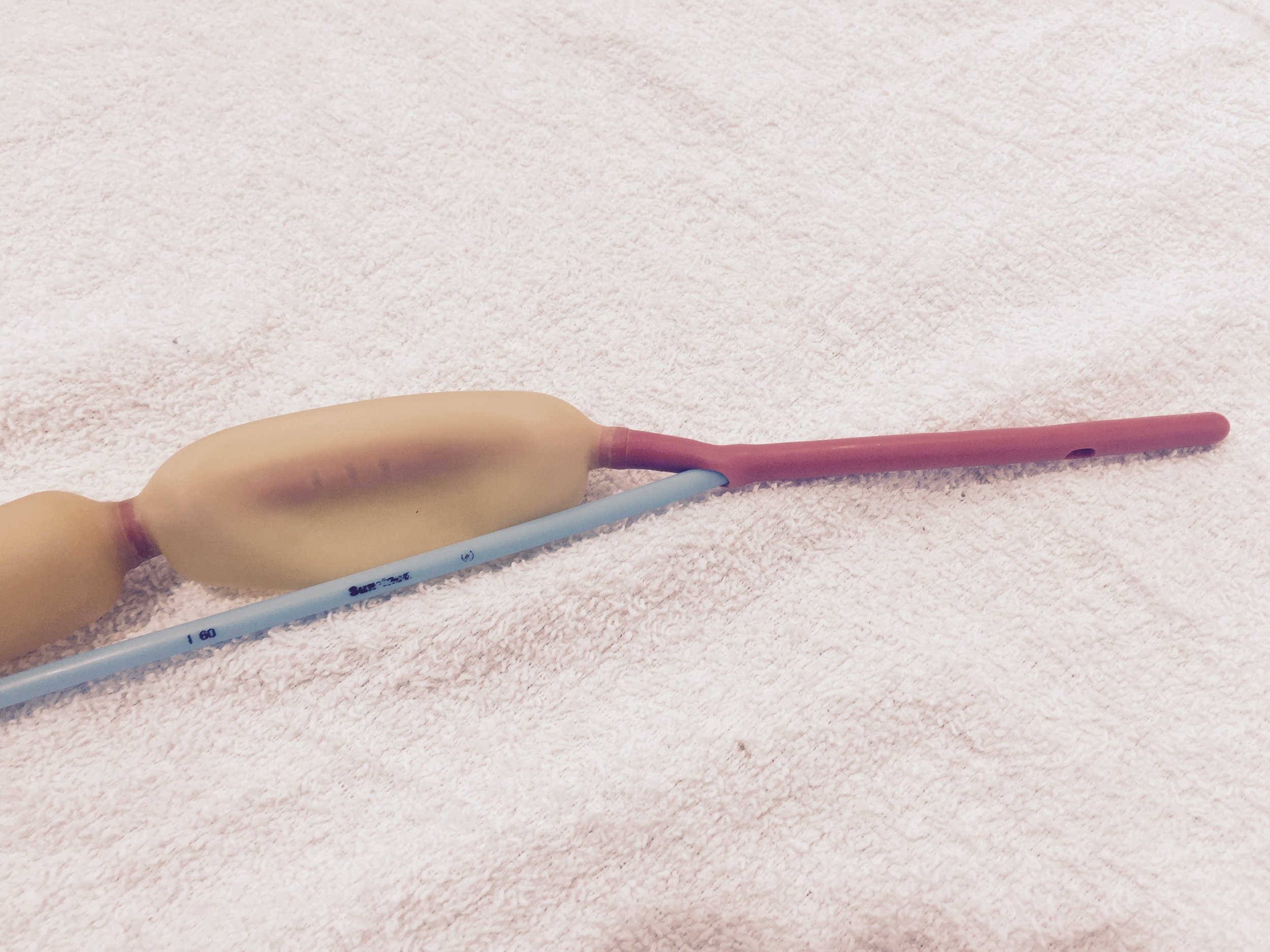

Bougie Assisted Minnesota Tube Placement:

A bougie may be used as an adjunct for assistance with placement of the Minnesota tube (7)

Place the straight end of the bougie (not the coude tip) into the most proximal of the three gastric aspiration ports, insert approximately 0.5 cm

The fully assembled apparatus may be inserted as an OG by pushing the bougie intentionally down the esophagus

Once fully inserted to 50 cm inflate gastric balloon with 50 mL of air and verify placement below diaphragm with CXR

Continue inflating gastric balloon to 500

In one swift movement remove the bougie. The inflated Minnesota tube will remain in place. Previous placement of the bougie in the most proximal of the three gastric aspiration holes should prevent folding of the distal Minnesota tube between the inflated gastric balloon and gastric fundus.

Other options for tube securement

Pulley traction using kerlix, 1 L NS, and IV pole

Tie kerlix to Minnesota tube

Attach kerlix to bag of saline

Hang over an IV pole

Take note of tube depth

Football helmet

Secure tube to face guard of a football helmet

Stretcher method

Tie kerlix to Minnesota tube

Tie other end of kerlix to foot of stretcher under 1-2 lbs of tension

Take note of tube depth

Note: this method places traction on the lower lip which could lead to skin breakdown, so is best used as a short-term solution in the transport environment.

Definitions:

Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (upper GI bleeding): bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract, i.e., proximal to the ligament of treitz. The most common source of upper GI bleeding is ulcerative disease, with esophageal and gastric variceal hemorrhage being the second. Other more rare causes include dieulafoy lesions and aortoenteric fistulas.

Esophagogastric variceal hemorrhage: bleeding from gastric or esophageal varices. Gastric varices tend to occur at the upper portion of the stomach near the esophageal junction. Hemorrhage occurs in the setting of portal hypertension as a result of liver cirrhosis. Common causes of liver cirrhosis include IV drug abuse leading to chronic hepatitis B/C infections, alcohol abuse leading to alcoholic cirrhosis, and obesity causing non-alcoholic steato-hepatitis (i.e. NASH, fatty liver disease).

TIPS (transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt): an interventional radiology endovascular procedure involving placement of an artificial shunt between the portal vein and the hepatic vein, decompressing the portal system, and reducing variceal hemorrhage. When endoscopy fails to control variceal hemorrhage TIPS is often the next step in management (2). Many patients being transferred to tertiary care centers from outside hospitals with upper GI hemorrhage are being referred specifically for potential TIPS placement. Other potential interventions include endovascular gastric vein ablation, and liver transplant.

Article by Bobby Whitford, MD

Peer Editing by Christian Renne, MD

References:

Bajaj, Sanyal. Methods to achieve hemostasis in patients with acute variceal hemorrhage. Saltzman, ed. UpToDate. Waltam MA: UpToDate INC https://www.uptodate.com/contents/methods-to-achieve-hemostasis-in-patients-with-acute-variceal-hemorrhage (accessed on July 23rd 2018).

Yoshida H, Mamada Y, Taniai N, et al. Treatment modalities for bleeding esophagogastric varices. J Nippon Med Sch. 2012;79(1):19-30.

Chojkier M, Conn HO. Esophageal tamponade in the treatment of bleeding varices. A decadel progress report. Dig Dis Sci. 1980;25(4):267-72.

Pasquale MD, Cerra FB. Sengstaken-Blakemore tube placement. Use of balloon tamponade to control bleeding varices. Crit Care Clin. 1992;8(4):743-53.

EMRAP Productions. Linton, Blakemore, Minnesota tubes overview. EMRAP HD. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yv4muh0hX7Y (accessed on July 23rd 2018).

EMRAP Productions. Using an ETAD for traction during variceal tamponade. EMRAP HD. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jHT79cxvaCo (accessed on July 23rd 2018).

Whitford, Hinckley. The Whitford Technique: Bougie-Aided Minnesota Tube Placement. May 27th 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BjyhGg1vBu0 (accessed on July 23rd 2018).

Sachar et. al. Intermittent vs Continuous Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy for High-Risk Bleeding Ulcers: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 November; 174(11): 1755–1762.

Gøtzsche PC1, Hróbjartsson A. Somatostatin analogues for acute bleeding oesophageal varices. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jul 16;(3):CD000193.

Chavez-Tapia NC, et.al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for cirrhotic patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Sep 8;(9):CD002907.

Bennett, C et.al. Tranexamic acid for upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Nov 21;(11):CD006640.

Roberts I, Coats T, Edwards P, et al. HALT-IT--tranexamic acid for the treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:450.

Mutschler M, Nienaber U, Münzberg M, et al. The Shock Index revisited - a fast guide to transfusion requirement? A retrospective analysis on 21,853 patients derived from the TraumaRegister DGU. Crit Care. 2013;17(4):R172.