Annals of B-Pod: Mastering Minor Care

/Fingertip Injuries

While injuries to the fingertip may appear small, the high concentration of sensory nerve endings make real estate in this area very expensive. Sensation at the fingertip as well as an intact support structure (nail apparatus, volar pad, and distal phalanx) are vital to a fully functioning hand. As such, injuries to this area can result in significant morbidity if not managed properly.

Despite the importance of treating these injuries appropriately, management strategies in this field of wound care vary considerably. This is, in part, due to the fact that there are few controlled studies looking at fingertip and fingernail problems. Joining us again for this installment of Mastering Minor Care is wound management guru Dr. Alexander T. Trott to address the correct management of some common fingertip injuries.

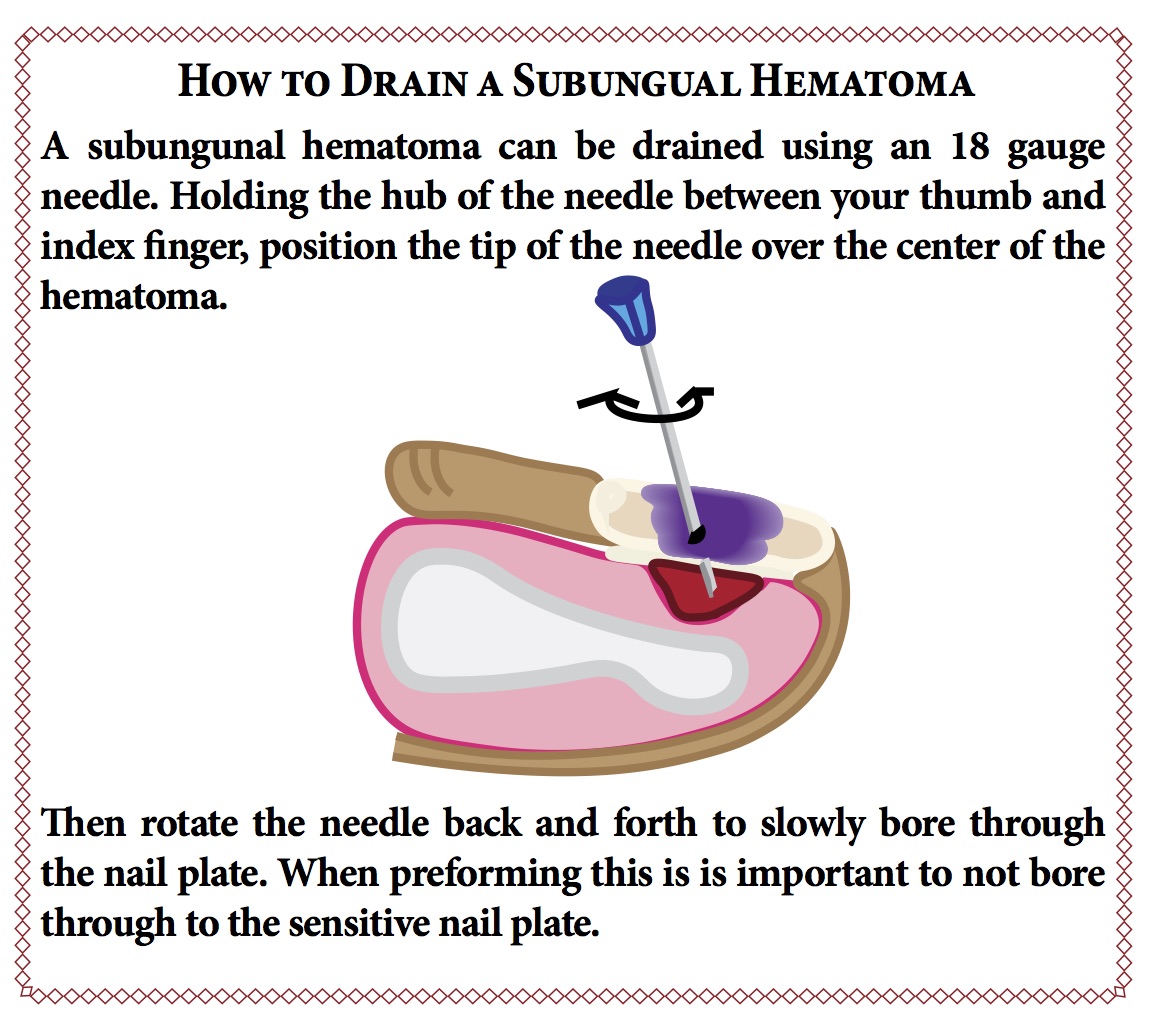

Subungual Hematoma

The management of subungual hematomas has simplified in recent years. It was once taught that if the size of the hematoma was greater than 50% of the nail surface, then there was a likelihood that a nail bed laceration was present. It was recommended that the nail be removed and the nailbed laceration repaired. That is no longer the case. No matter what the size of the hematoma, if the nail itself is intact, in proper position and not loose, then simple trephination alone is carried out. Any nailbed laceration will heal well without the need of sutures.

On the other hand, if the nail is loose, it should be taken off. Any bed laceration is repaired with two or three absorbable sutures to provide stability of the bed that is lost without an intact nail in place.

With subungual hematomas, there can be an accompanying distal phalanx or tuft fracture. These might be considered open fractures but they do not require prophylactic antibiotics. After trephination or bed repair, a simple aluminum hockey stick splint can be applied over a non-bulky, non-adherent dressing.

If the nail is removed and the bed repaired, is has been routine to temporarily replace the nail to prevent the cuticle from adhering to the nailbed. That practice has been called into question and can cause an increase in complications.

Avulsion-Tissue Loss Injuries

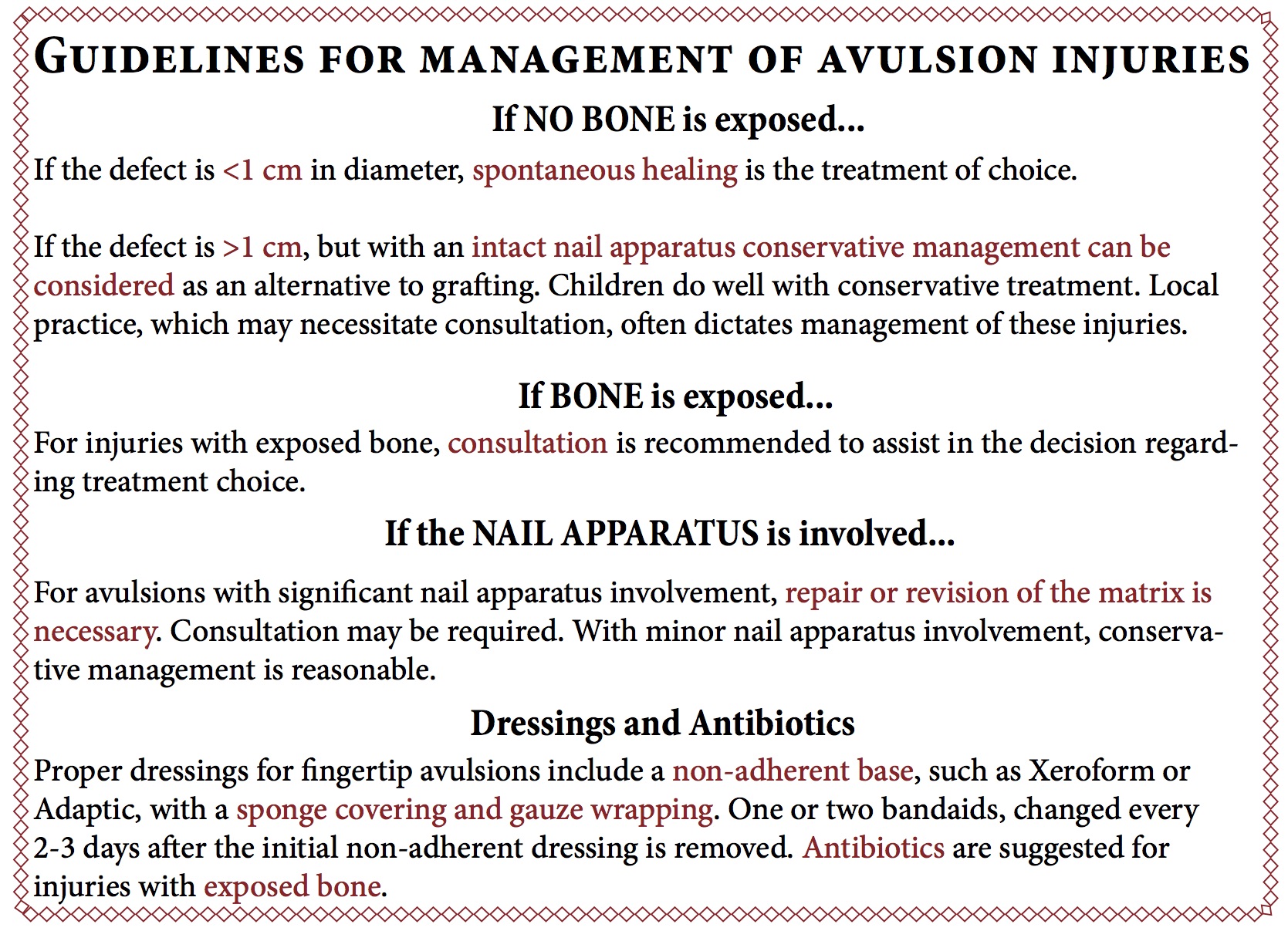

These injuries can vary from a small oval avulsion from dicing a tomato to a large, mutilating injury from a machine tool accident. The decision to manage the wound by the emergency physician or get a consult depends to some degree on the comfort of the practitioner. Exposed bone, complex fractures, tissue distortion and necrosis are indicators for consultation, as is probable need for an amputation-revision.

It has long been held that any superficial fingertip tissue loss that measures 1 cm squared or less can be managed by spontaneous healing (secondary intention). This assumes that no bone is exposed and the nail apparatus is intact. Other studies, however, show that larger avulsions up to 1 ½ by 2cm in size can also be managed similarly. Even if the tip of the distal phalanx can be seen or a small portion of the nail bed is involved, spontaneous healing will provide excellent coverage, with sensation restored. The complication rate is virtually nil, whereas it is 20-25% with grafting or flap repair.

It takes 3-4 weeks for an avulsion to heal. The patient needs to keep the wound clean with soap and water. One or two bandaids, changed every 2-3 days after the initial non-adherent dressing is removed, provides adequate coverage.

Authored by Benjamin Ostro, MD

Posted by Grace Lagasse, MD