These pages contain the most up-to-date descriptions, guidelines, videos, and resources we can find.

Procedure Videos

Recent Posts on Procedural Education

Dr. Gabor reviews normal anatomy and pathology of the Bartholin gland, and discusses multiple treatment strategies to manage this condition.

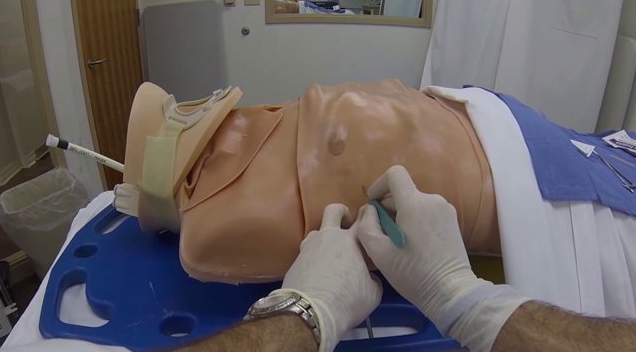

Subclavian central lines have historically been a landmark based procedure. While for years IJ and femoral central venous access had move to being primarily ultrasound guided (or entirely ultrasound guided), the subclavian line was a long standing holdout. As such, providers may be unfamiliar with some of the pearls that can facilitate performance of the procedure with ultrasound. In this post, Dr. Ben Duncan, ultrasound fellow discusses some of the ways to help make ultrasound work for you while trying to perform a subclavian line.

The subclavian central line, whether using an infraclavicular or supraclavicular approach can strike fear in the novice proceduralist. Big needles traversing near and seemingly towards a patients lung apex is not exactly a comforting vision. However, like with most procedures, a firm understanding of the anatomy at play will give the operator confidence as they approach what is a critical central venous access procedure particularly in crashing patients.

Shoulder looking off and don’t have / have time to look for an XRay? Join Dr. Kate Connelly as she takes us through the sonographic evaluation of shoulders and real time evaluation of dislocation reductions.

This month, the Taming the SRU ultrasound team details some of the procedural applications of ultrasound in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, fresh from two of the minds our intern class: Drs. Hamza Ijaz and Chris Zaleky. This combo post will discuss the use of ultrasound to confirm placement of both endotracheal tubes and central venous catheters.

Prior to the widespread availability of point-of-care ultrasonography, invasive medical procedures were performed by the “landmark method”. Landmark methods are based on surface anatomy, palpation, and sometimes trigonometry, and are fraught with the potential for error. Complications, while unquantified in the misty past, were likely much more common than in the current era of readily available bedside imaging. Vascular access procedures are inarguably safer and more successful when guided by sonography, but interpretation of ultrasound images still requires an understanding of both surface and deeper anatomy to relate the two-dimensional screen image to three-dimensional reality. Further, there are circumstances where either the urgency of the resuscitation, or compromised access to the patient, requires that vascular access be obtained using landmarks rather than real-time imaging. In such cases a detailed understanding of regional anatomy is critical to maximize procedural success and minimize complications.

Lumbar punctures can be mercurial procedures. There are certainly patients in whom it can be predicted that a lumbar puncture will be challenging. Obesity, patients with known degenerative changes, and agitated patients all present unique challenges when it comes to successfully completing a lumbar puncture. There are patients, however, who throw you a bit of a curveball. Sometimes cooperative patients with good landmarks, in whom you had every expectation that you would find success, become seemingly impossible to successfully complete a lumbar puncture.

For the provider, knowing how to troubleshoot the unexpectedly difficult lumbar puncture can be the difference between success and failure.

Have you ever looked down the blade of a laryngoscope and said to yourself, “Damn! This airway is just too dry!” I thought not. Rather, we often look down the blade into a mucky swamp of secretions that drip from the pharyngeal walls like drool from a big, sloppy dog, and often obscure familiar landmarks and goop-up our optical and video adjuncts. Is there no solution? There is! Let us review an illustrative case...

Case 1

CC: Laceration to Upper Lip

HPI: 23 year old male presents to the ED with laceration to his upper lip. Patient states he was “Minding his own business” when all of the sudden the ground came up and hit him in the face. His friend alcohol might have been there. Patient states he now has a cut on his lip and a bruise on his pride.

Physical Exam: Physical exam demonstrates a 2 centimeter full thickness laceration of the left upper lip that crosses the vermillion border.

General Considerations

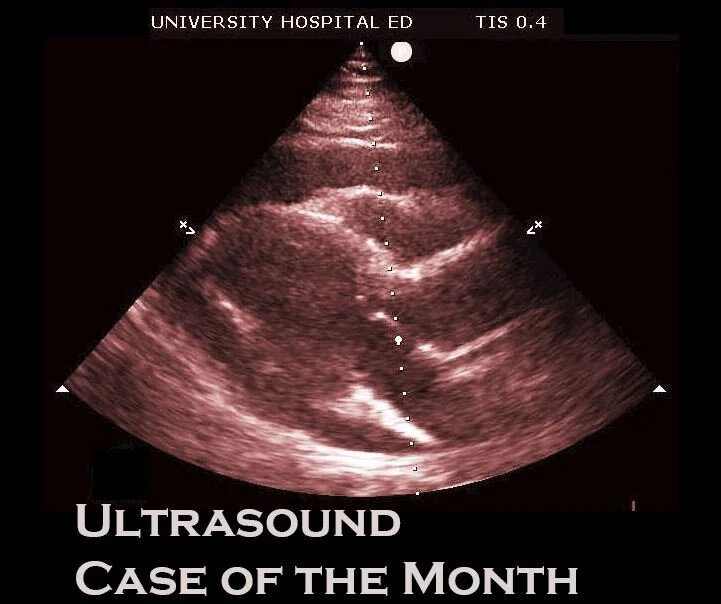

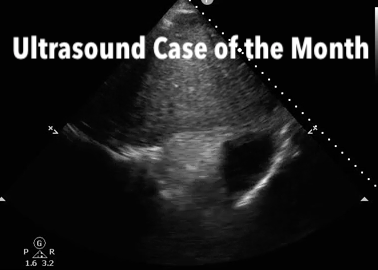

Both the diagnostic and therapeutic thoracenteses are performed using a similar technique. The major difference is the amount of fluid removed. The proceduralist may also choose to only use the needle technique as opposed to the needle-catheter unit when obtaining fluid for diagnostic purposes only.

It is generally recommended that needle size be limited to 18-gauge or smaller to minimize risk of pneumothorax and damage to nearby structures.

US-guided thoracentesis is associated with a significantly lower rate of complications and has become the standard of care. (1) Real-time ultrasound (US) guidance is recommended for small or loculated effusions when there is concern that the diaphragm or lung tissue is <10mm from the pleural surface. It is also recommended in patients with relative contraindications such as coagulopathies and the mechanically ventilated patient.