PERCs of the Wells Score

/Pulmonary embolism (PE) is one of the big “can’t miss” diagnoses in the emergency department. Unfortunately, presenting symptoms are often vague, and definitive diagnostic testing is expensive and comes with risks of radiation and contrast to the patient. In order to avoid missing a PE while mitigating the risks associated with overtesting, some clinical decision tools have been created to aid in the diagnostic process. We will focus on two of these commonly used decision tools: the PERC rule and the WELLS score for PE.

The WELLS score

The WELLS score was created by Philip Steven Wells in 1995 to risk stratify patients for PE and was further developed over the next few years into two different models. The initial goal of the study was to help determine which patients were sufficiently low risk to rule out further testing with a d-dimer. (1) Patients met inclusion criteria for the study if PE was suspected, symptoms had been present for less than 30 days, and patients had acute onset of new or worsening dyspnea or chest pain. (1) Patients were excluded from the study if they were pregnant, were less than 18 years old, had no symptoms of PE within 3 days of presentation, had been on anticoagulation for more than 24 hours, had an expected survival time of less than 3 months, had a contraindication to contrast, or had a “geographic inaccessibility precluding follow-up.” Patients were also excluded if upper extremity DVT was suspected as a source of PE. (1)

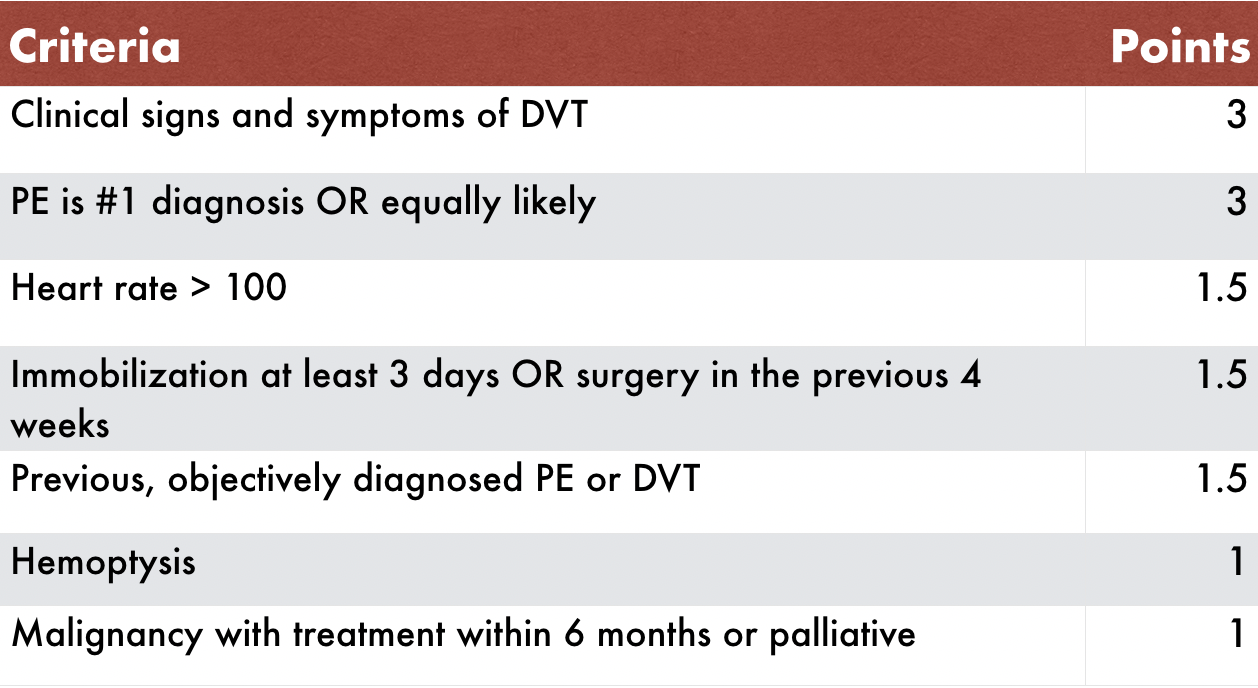

The WELLS score assigns points to certain clinical signs and symptoms as shown by the chart below (2):

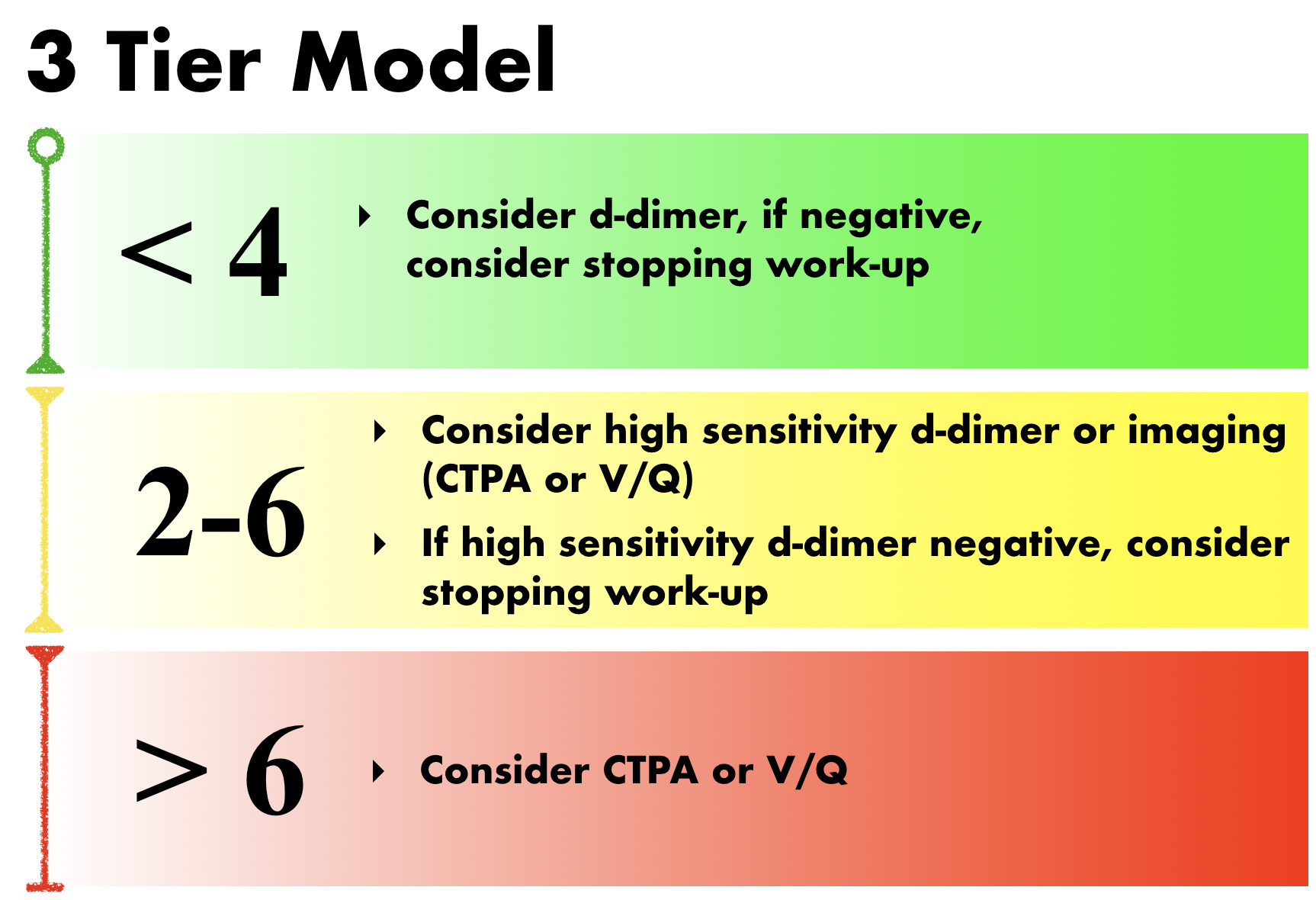

This score can then be applied to either a three-tier model or a two-tier model. The three-tier model was developed first. In the original study, PE prevalence was found to be 1.3% in the low-risk group, 16.2% in the moderate risk group, and 37.5% in the high-risk group. When combined with a negative d-dimer, the negative predictive value was 99.5% for the low-risk group, 93.9% in the moderate-risk group, and 88.5% in the high-risk group. (1) Therefore, the current recommendations when using the three-tier model are as follows (2):

The original study showed that applying this decision rule limited the need for diagnostic imaging to 53% of patients. (1) A recent study showed that 86.5% of patients who underwent CTPA based on clinical suspicion fell into the low or moderate risk categories based on WELLS. (3) Therefore, applying the WELLS score can significantly reduce unnecessary imaging.

The WELLS score was validated by another study, which found similar rates of PE among the three groups. (4) The Christopher study then further validated the WELLS score and simplified it into two risk stratification groups, thus using a more conservative threshold for recommending CTPA. (5) Recommendations for using the two-tier model are as follows (2):

The Christopher study found a 12.1% incidence of PE in the “unlikely” group and a 37.1% incidence in the “likely” group. Applying their two-tier decision rule resulted in a PE miss rate of only 0.5% on 3 month follow up. (5)

Which is better, the three-tier or two-tier model?

Using the three-tier model, a high sensitivity d-dimer assay was found to safely rule out PE in both low and moderate risk groups, but a moderately sensitive d-dimer was only sufficient to rule out PE in the low risk group. However, a moderately sensitive d-dimer does safely exclude PE in “PE unlikely” patients using the two-tier model. (6) Therefore, guidelines favor using the dichotomous rule. (2,6) Our TamingtheSRU algorithm for diagnosing PE supports this and can be found here.

The PERC rule

In patients that are low risk based on either WELLS or clinical gestalt, another option is to use the PERC rule instead of a d-dimer to rule out PE. This can help avoid the problem of dealing with a positive d-dimer in a patient whom you really do not think has a PE. The PERC rule was created in 2004. Patients were included in the study if a board-certified emergency medicine physician believed a formal evaluation for PE was necessary. (7) Exclusion criteria included age less than 18 years old or shortness of breath not being the most or equal most important complaint. The original study also stated that the following patients should not be considered eligible for application of the PERC rule:

Known thrombophilia

Strong family history of thrombosis

Concurrent beta-blocker use (could blunt reflex tachycardia)

Transient tachycardia

Patients with amputations

Massively obese patients in whom unilateral leg swelling could not be assessed

Patients with baseline SaO2 of < 95%

Using the PERC rule, PE can be excluded if the clinician’s gestalt pre-test probability is < 15% and none of the following criteria are met (8):

Age ≥50

HR ≥ 100

SaO2 on room air < 95%

Unilateral leg swelling

Hemoptysis

Recent surgery or trauma (≤4 weeks ago requiring treatment with general anesthesia)

Prior PE or DVT

Hormone use (oral contraceptives, hormone replacement, or estrogenic hormones use in males or females)

The PERC rule was validated in 8138 patients at 13 emergency departments and, combined with a gestalt clinical suspicion for PE <15%, was found to exclude PE in 20% of cases with a false negative rate of 1%. (9) This miss rate is justified based on an estimated point of equipoise of 2% using the Pauker and Kassirer method. (9) For patients with a pretest probability below that threshold, the risk of initiating further workup and treatment is equivalent to the risk of missing a PE. Based on this, ACEP clinical policy supports use of the PERC rule to exclude PE in low-risk patients, citing potential benefits as reduced test complications, costs, and time in the ED. (10)

Limitations

When used appropriately, both the PERC rule and the WELLS score can safely reduce diagnostic testing when evaluating patients for PE. However, both have limitations. The WELLS score in particular has been criticized for being subjective since one criterion is a belief that PE is the #1 or equally likely diagnosis. Additionally, there is some evidence that clinical gestalt performs better than WELLS when assessing clinical probability of PE. (11)

The most important thing to remember is that these decision rules do not replace clinical judgment. The PERC rule requires a clinical suspicion of <15% before it can be applied; it should notbe applied to all patients in whom you are considering PE. Similarly, the WELLS score is notmeant to be used on all patients with chest pain or dyspnea; you must first have a genuine clinical suspicion for PE. Furthermore, these tools do not force you to order any diagnostic testing. A positive PERC is not an indication for ordering a d-dimer, and a high-risk WELLS score does not necessarily mean you must order a CTPA.

As long as you continue to think through each individual patient, these tools can be helpful in finding the appropriate balance between being too conservative and too cavalier about PE.

References

Wells, P. S., et al.“Excluding Pulmonary Embolism at the Bedside without Diagnostic Imaging: Management of Patients with Suspected Pulmonary Embolism Presenting to the Emergency Department by Using a Simple Clinical Model and d-Dimer.” Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 135, no. 2, July 2001, pp. 98–107.

Wells' Criteria for Pulmonary Embolism - MDCalc. Mdcalc.com. https://www.mdcalc.com/wells-criteria-pulmonary-embolism#evidence. Published 2019. Accessed April 19, 2019.

Mittadodla, Penchala S., et al. “CT Pulmonary Angiography: An over-Utilized Imaging Modality in Hospitalized Patients with Suspected Pulmonary Embolism.” Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives, vol. 3, no. 1, Jan. 2013, p. 20240. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, doi:10.3402/jchimp.v3i1.20240.

Wolf, Stephen J., et al.“Prospective Validation of Wells Criteria in the Evaluation of Patients with Suspected Pulmonary Embolism.” Annals of Emergency Medicine, vol. 44, no. 5, Nov. 2004, pp. 503–10. PubMed, doi:10.1016/S0196064404003385.

Gibson, Nadine S., et al. “Further Validation and Simplification of the Wells Clinical Decision Rule in Pulmonary Embolism.” Thrombosis and Haemostasis, vol. 99, no. 1, 2008, pp. 229–34. www.thieme-connect.com, doi:10.1160/TH07-05-0321.

Torbicki, Adam, et al.“Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary EmbolismThe Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).” European Heart Journal, vol. 29, no. 18, Sept. 2008, pp. 2276–315. academic.oup.com, doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehn310.

Kline, J. A., et al.“Clinical Criteria to Prevent Unnecessary Diagnostic Testing in Emergency Department Patients with Suspected Pulmonary Embolism.” Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, vol. 2, no. 8, 2004, pp. 1247–55. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00790.x.

“PERC Rule for Pulmonary Embolism.” MDCalc, https://www.mdcalc.com/perc-rule-pulmonary-embolism. Accessed 28 Apr. 2019.

Kline JA, et al:Prospective multicenter evaluation of the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria.J Thromb Haemost 2008; 6:772-780.

Wolf SJ, et al.Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Evaluation and Management of Adult Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department With Suspected Acute Venous Thromboembolic Disease. ACEP Clinical Policy, February 2018.

Penaloza A, et al.Comparison of the Unstructured Clinician Gestalt, the Wells Score, and the Revised Geneva Score to Estimate Pretest Probability for Suspected Pulmonary Embolism. Annals of Emergency Medicine, vol. 62, no. 2, August 2013, pp. 117-124.

Authorship

Written by Christina Pulvino, PGY-1, University of Cincinnati Department of Emergency Medicine

Peer Review and Editing by Jeffery Hill, MD Med