Consultant Corner: Acute Management of the Dislocated Knee

/Acute knee dislocations are rare orthopedic injuries that have high morbidity and need to be recognized quickly by the emergency physician; if unrecognized or inadequately treated, these injuries can lead to vascular and limb compromise (1,2). Knee dislocations make up less than 0.5% of all orthopedic injuries and may be difficult to recognize if the dislocation spontaneously reduces prior to care in the Emergency Department, which may occur in upwards of 50% of cases (3). Neurovascular injury is a common and feared complication of knee dislocation, occurring in 40-64% of patients (4). Reducing the total ischemic time in patients with vascular injury is the single most important variable in improving outcomes and reducing the risk of amputation; an ischemic time of >8 hours is associated with amputation rates of up to 85%, compared with <20% in those with ischemic time of <8 hours (2). Knee dislocations can occur in both high- or low-velocity mechanisms, but ultra-low velocity knee dislocations occurring with activities of daily living such as walking are becoming more common, especially in patients with morbid or super morbid obesity (5).

Anatomy

The knee joint is composed of the articulating surface between the femur and the tibia and is stabilized by a complex combination of ligaments, cartilage, tendons, and muscles.

Ligaments including the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), medial collateral ligament (MCL) and lateral collateral ligament (LCL) all help to prevent excessive translational forces to stabilize the knee. The medial and lateral menisci support axial forces and help prevent excessive rotational forces (1). The popliteal artery and peroneal nerve pass through the knee in close proximity to these structures and are at high risk of injury (1).

Classification of knee dislocations

There are several different classification systems used to describe knee dislocations (4). The three most common are (a) mechanism of injury classification, (b) kennedy positional classification system, and (c) schneck (ligamentous) classification system

-

Knee dislocations may be categorized as high-velocity, low-velocity, and ultra-low velocity.

High-velocity dislocations are caused by sudden, extreme forces such as motor vehicle accidents or high velocity direct trauma, i.e. pedestrian struck or a fall from a significant height.

Low-velocity injuries occur usually in sports settings. (1)

Ultra-low-velocity injuries occur with activities of daily living, such as walking. (5)

The utility of this classification system is questionable, as prognosis and vascular injury rates are similar between high and ultra-low velocity dislocations. (4)

-

This classification system describes the position of the tibia relative to the femur. Categories include anterior, posterior, medial, lateral, and rotary. This classification is simpler and more intuitive to use. However, it cannot be used on dislocations that self-reduce prior to presentation. (4)

Anterior: Most common, usually occur with a forced hyperextension injury (1,4)

Posterior: Often occur due to a direct blow to a flexed knee, i.e. striking a dashboard (2)

Rotary: Subdivded into anteromedial, anterolateral, posteromedial, and posterolateral. Posterolateral rotary dislocations are the least common and often require open reduction in the OR (1)

-

This classification system categorizes the knee dislocation based on the degree of ligamentous injury. (4) This classification system is more specific but may be impractical to use in an Emergency Department setting. (1,4)

Class 1: one cruciate ligament disrupted (ACL or PCL)

Class 2: Both cruciate ligaments disrupted (ACL + PCL)

Class 3: Both cruciate ligaments + 1 collateral ligament disrupted (ACL and PCL + MCL or LCL)

Class 4: Both cruciate ligaments + both collateral ligaments disrupted (ACL, PCL, MCL, + LCL)

Class 5: Fracture-dislocation

History and Physical Examination

Especially in cases of high-velocity injuries, the emergency physician should first stabilize and manage life-threatening injuries by performing a primary survey and resuscitating as indicated.

Then, after turning attention to the affected extremity, a careful history is important to discover the mechanism of injury. Reports of a pre-hospital deformity, “popping” sensation, or reduction attempts should raise suspicion for a spontaneously reduced knee dislocation. It is also important for the emergency physician to ask about previous surgeries on the affected knee, as well as anticoagulation status. Any report of severe pain, coolness, weakness, or paresthesias raise suspicion for a vascular injury.

Knee dislocations will usually present with an gross deformity of the affected knee, but if the dislocation was reduced pre-hospital, the knee may look grossly normal, especially if the patient’s anatomic landmarks are difficult to appreciate due to obesity (1). Joint effusions may not be immediately apparent if the joint capsule is ruptured (1).

A careful skin examination is needed to assess for wounds suggestive of an open fracture or traumatic arthrotomy, skin necrosis, or any dimpling or puckering of the skin, as these can indicate an irreducible dislocation that must be reduced in the operating room.

A detailed vascular exam can identify hard signs of a vascular injury such as absent pulses, distal ischemia, a rapidly expanding hematoma, bruits, or arterial bleeding (1,4). Doppler should be used at the bedside to assess pulses if they are not palpable. Importantly, normal distal pulses or doppler signals do not rule out a significant vascular injury in the setting of high suspicion for vascular injury (1,4).

The emergency physician should also perform a stability examination to identify any possible ligamentous injuries, including Lachman’s maneuver or pivot-shift tests, posterior sag or posterior drawer tests, and valgus/varus stress testing. Notably, a full ligamentous exam may be difficult to perform during the acute phase of injury due to significant pain or muscular spasm (1). A simple test for the emergency physician to perform is to apply gentle varus stress to the affected knee while the knee is fully extended; if laxity is identified, this indicates multi-ligament instability and raises concern for a knee dislocation event.

Finally, sensory and motor testing should be performed to evaluate for neurologic injury (1). Peroneal nerve injuries are common in knee dislocations, which can manifest as weakness with both foot eversion and dorsiflexion (“foot drop”) as well as varying degrees of numbness along the distributions of the superficial peroneal nerve (anterolateral leg) or the deep peroneal nerve (first dorsal webspace) (6).

Diagnostics and Management

Although many knee dislocations are diagnosed clinically, x-rays (AP and lateral) are the usual test-of-choice and should be obtained to evaluate for factors that may prevent a successful reduction, such as associated fracture. However, obtaining images should not delay reduction attempts, especially if there is evidence of a neurovascular injury (1,2).

Closed reduction is best performed with two providers: one to stabilize the femur and one to apply in-line traction by gripping the knee at the proximal tibia and applying longitudinal traction to bring the knee into extension. Anterior or posterior pressure should be applied if in-line traction alone does not provide adequate reduction. After reduction, the knee should be placed in a splint or hinged knee brace at 20 degrees of flexion to prevent further vascular injury (10). Post-reduction x-rays are necessary. Neurovascular status should be immediately reassessed after any reduction attempt.

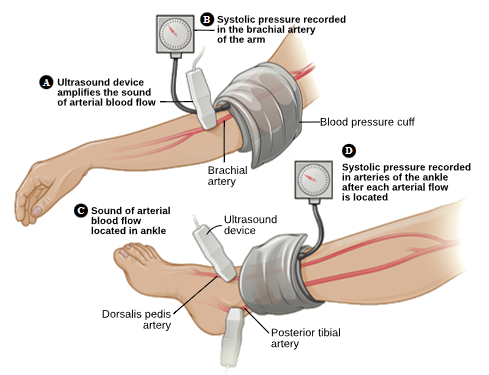

All patients with suspected knee dislocations should undergo an ankle-brachial index (ABI) after reduction to further evaluate for vascular injury, even if the injury has self-reduced prior to the emergency physician’s evaluation. An abnormal ABI (<0.9) had 100% sensitivity and specificity for significant vascular injury in one study (8). If an ABI is abnormal or there is significant clinical suspicion for vascular injury, the patient should either proceed to the operating room for surgical management in conjunction with orthopedic and vascular surgery or undergo computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the affected leg for further evaluation. CTAs have the added benefit of also further evaluating the surrounding osseus structures for associated fracture. If a vascular injury is identified on CTA, vascular surgery should be consulted for further management.

Even if initial ABI and/or CTA are normal and work-up is reassuring without any associated vascular injury, patients with high suspicion of a knee dislocation usually still require admission (or prolonged ED stay) for observation and serial vascular examinations. This decision is typically made in conjugation with orthopedic surgery.

Case example

Patient 1 is a middle aged female with a PMH of anemia, PCOS who presented with acute right knee pain and deformity as she was running through the woods and felt her right knee give out from underneath her. She presented to the Emergency Department at which time radiographs demonstrated a medial knee dislocation.

Pertinent physical exam findings prior to reduction included obvious deformity at the knee with palpable distal femoral condyles underneath the skin, peroneal nerve distribution paresthesias, and absent DP, PT pulses. No open wound.

The patient underwent successful closed reduction under conscious sedation in the Emergency Department with a combination of Ketamine and Propofol.

Both PT and DP pulses after reduction were palpable. ABI’s were 1.1 bilaterally. CT angiography was deferred. The patient was placed into a knee immobilizer and admitted under ED Observation for monitoring and MRI completion. MRI of the knee revealed a right multi-ligamentous knee injury with injury to the ACL, PCL, MCL, posterolateral corner, and medial trochlea articular cartilage.

The patient was transitioned to a hinged knee brace locked in extension, kept non-weight bearing, and discharged with Orthopaedic Sports Medicine follow up within one week. She then underwent scheduled multi-ligamentous knee reconstruction with ACL, PCL, and PLC reconstruction.

She continues to do well post operatively with her rehabilitation program. After wound healing, she partook in a a dedicated regimen of restoring motion, strength, and finally graduated with return to sport.

post by Sarah Moulds, MD and Sean Catlett, MD

Dr Moulds is a PGY-3 in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati

Dr Catlett is a PGY-4 in Orthopedic Surgery at the University of Cincinnati

editing by bret betz, md and brian grawe, md and daniel gawron, md

Dr Betz is an Associate Professor in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati with fellowship training in sports medicine. He works in both the emergency department as well as the sports medicine clinic. He is also one of the team physicians for the Cincinnati Bengals.

Dr Grawe is a Professor in Orthopedic Surgery at the University of Cincinnati with fellowship training in sports medicine and shoulder reconstruction. He is also one of the team physicians for the Cincinnati Bengals.

Dr Gawron is an Assistant Professor in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati with fellowship training in sports medicine. He works in both the emergency department as well as the sports medicine clinic.

References

Gottlieb M, Koyfman A, and Long B. Evaluation and management of knee dislocation in the emergency department. J Emer Med. 2020;58(1):34-42.

Perron AD, Brady WJ, Sing RF. Orthopedic pitfalls in the ED: Vascular injury associated with knee dislocation. J Emer Med. 2001;19(7):583-588.

Chowdhry M, Burchette D, Whelan D, Nathens A, Marks P, and Wasserstein D. Knee dislocation and associated injuries: An analysis of the American College of Surgeons National Trauma Data Bank. Knee Surg Sports Tr A. 2020;28:568-575.

Figueras JH, Johnson BM, Thomson C, Dailey SW, Betz BE, and Grawe BM. Team approach: Treatment of traumatic dislocations of the knee. JBJS Reviews. 2023;11(4)

Smith PJ, Azar FM. Knee dislocations in the morbidly obese patient. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2020;28(3)110-115.

Lezak B, Massel DH, and Varacallo M. Peroneal nerve injury. 2023. StatPearls.

Jeevannavar SS, Shettar CM. BMJCaseRep Published online: [Oct 4 2013] doi:10.1136/bcr-2013201279

Stannard JP and Schreiner AJ. Vascular injuries following knee dislocation. J Knee Surg. 2020;33(4):351-356.