Under Pressure - Compartment Syndrome Diagnostics

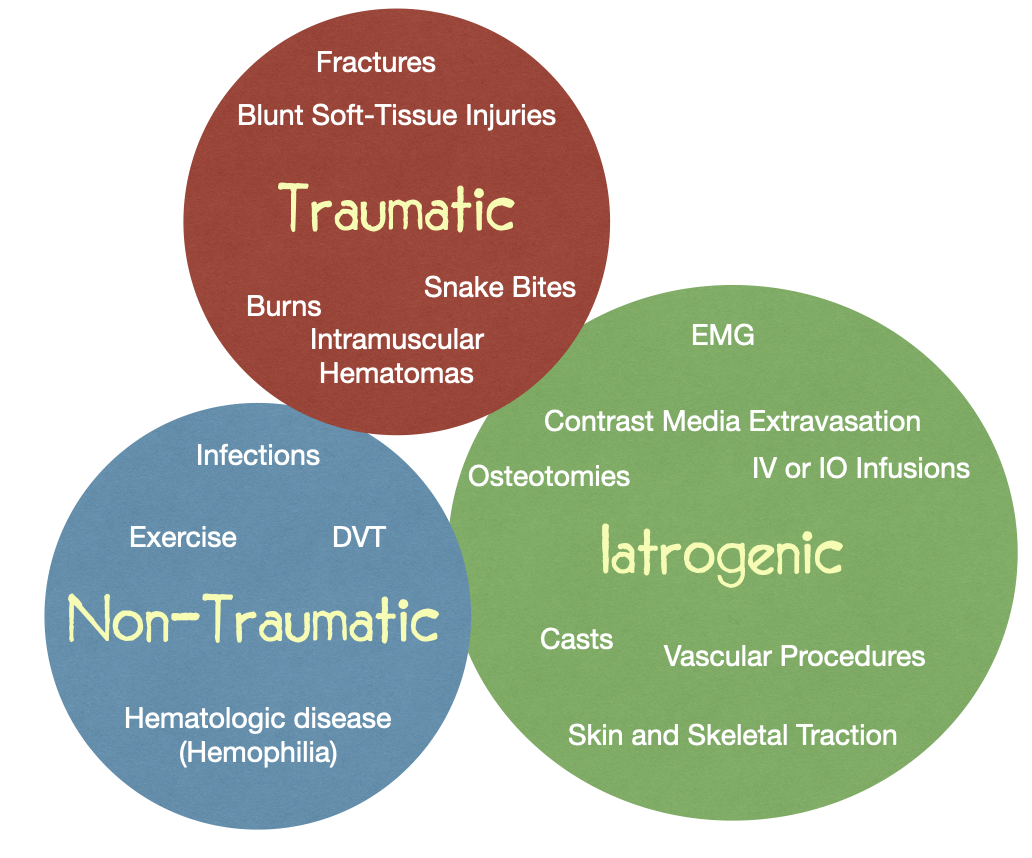

/Compartment syndrome is a surgical emergency that can present after a variety of insults, ranging from those we commonly encounter in the ED (fractures, crush injuries) to more rare clinical presentations (snake bites, electrocution). The initial elevation of compartment pressures can be secondary to internal (ex. bleeding, swelling, fluid overload) and/or external (ex. compressive devices, burn eschar) factors.

Compartment syndrome is defined as ongoing ischemia within the affected fascial muscle compartment, arising when there is increased pressure within a fixed volume leading to reduced venous return leading to additional increased compartment pressure leading to reduced capillary perfusion leading to decreased O2 delivery within compartment leading to myocyte necrosis leading to nerve injury.

Fractures account for 75% of cases of acute compartment syndrome, with tibial fractures followed by distal radius being the most common culprits. (2) Compartment syndrome occurs most often in patients <35 years of age and is 7-10 times more common in men compared to women due to a variety of factors including increased muscle bulk within compartments at baseline as well as higher rates of extremity trauma. (1, 12) It is important to remember that patients with bleeding diathesis at baseline (ex. hemophilia) are also at higher risk for compartment syndrome (1).

History and Physical

Adapted from Long, B, Koyfman, A. https://www.acepnow.com/article/tips-for-quickly-diagnosing-compartment-syndrome/2/

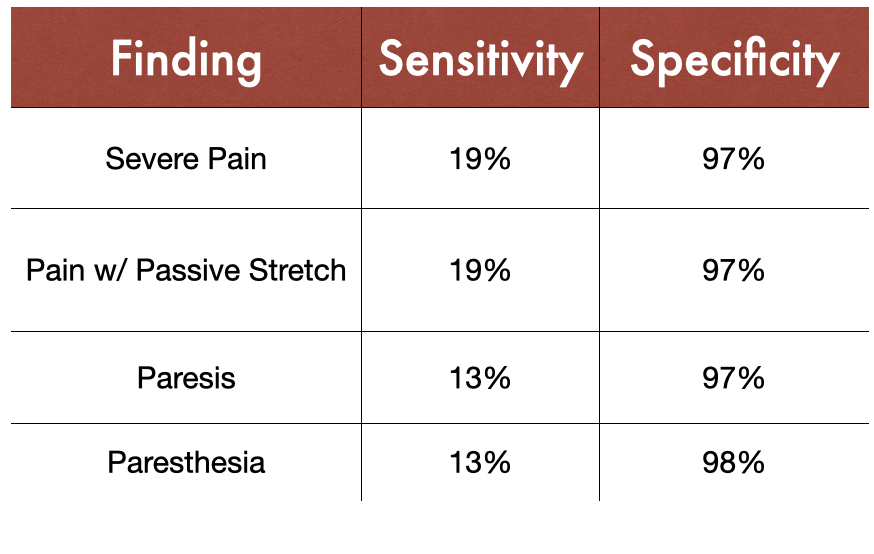

Acute compartment syndrome typically presents soon after inciting injury, and often the initial complaint from the patient may be subtle, with numbness, tingling, and paresthesia being some of the earliest signs. (3) Pain is typically most notable with passive stretch and is not relieved by pain medications including morphine. (2) The classic teaching of compartment syndrome presentation is the 6 P’s: Pain (especially with passive stretch), pallor, perishingly cold, pulselessness, paralysis, and paresthesia. Studies have shown that it is not each symptom alone but the combination of these symptoms that increases sensitivity of this diagnosis. (8) For example, the combination of pain at rest, pain with passive stretch, and paresthesia has a sensitivity of 93% for compartment syndrome, and adding paresis increases this to 98%. (8)

The earliest objective clinical finding on physical exam is a tense “wood like” feeling of the compartment. (14) Palpate for tenseness in addition to coolness, tenderness, and sensation changes including two-point discrimination. Of note, pulselessness, paralysis, and pallor tend to be very late findings in compartment syndrome and should not be used to exclude this diagnosis.

Evaluation / Diagnosis

The diagnosis of compartment syndrome relies heavily on clinical judgement, based on both the patient’s history and physical exam, followed by the diagnostic adjunct of measured compartment pressures. XR imaging is useful in identifying coinciding fractures and soft tissue swelling but should not delay next steps in management including fasciotomy because diagnostic capability is limited. US imaging has not been well studied in the diagnosis of acute compartment syndrome, but recent studies in cadaveric models suggest it could be a potential future non-invasive adjunct. (13) US can also be useful in the differential diagnosis of compartment syndrome, as DVT can have a similar presentation. Lab work plays little to no role in the diagnosis of compartment syndrome itself. However, patients on anticoagulants and those with bleeding disorders do require coagulation assays and factor levels as this affects the treatment plan. Patients also require pre-op labs for planned fasciotomy. Rhabdomyolysis has been reported to be associated with acute compartment syndrome in as high as 23%-40% of cases (1, 10, 11). As rhabdomyolysis is a potential complication of this condition, lab work including renal panel, electrolytes, calcium, phosphorus, as well as CK and urine myoglobin can help aid in the initial detection and monitoring of this complication and its sequelae.

Adapted from Long, B, Koyfman, A. https://www.acepnow.com/article/tips-for-quickly-diagnosing-compartment-syndrome/2/

The normal pressure in a muscle compartment is less than 10 mmHg, and blood flow may start to be compromised at pressures greater than 20 mmHg. The threshold for absolute intra-compartmental pressure to cause tissue ischemia has been debated, and the main reasons for this are: 1) different compartments have varied baseline compartmental pressures and 2) these pressures can vary from individual to individual; this prompted Whitesides to introduce the concept that the ischemic pressure threshold within a compartment can be more reliably related to the perfusion pressure. (7) The concept is like that of the CPP in brain injury, where the △ pressure = diastolic pressure - intra-compartmental pressure. If the absolute pressure >30 mmHg in any patient, >20 mmHg in hypotensive patient, △ pressure is <20-30 mmHg, there has been interrupted arterial perfusion for >4 hours, and/or clinical signs are present, consultation of orthopedic surgery for emergent fasciotomy is recommended. (4) For indeterminate pressure measurements and/or early symptoms, serial examinations should be pursued given risk of progression. (18)

Stryker Setup for Extremity Compartment Pressures

The Stryker monitor has a diagnostic sensitivity around 95 percent, with specificity greater than 98 percent. (15-17)

Arterial Line Setup for Extremity Compartment Pressures

Management

These patients require early surgical consult, as the only definitive management in compartment syndrome is relieving the pressure with fasciotomy. If fasciotomy is performed within 6 hours, nearly 100% of patients have recovery of limb function, and when this time frame is extended to 12 hours this decreases to 66% of patients with functional recovery. (14) In very delayed cases, amputation may be required, and the risks of fasciotomy outweigh benefits past 36 hours of injury. (14) Other important interventions include:

Providing supplemental oxygen and pressure support as indicated by VS

Removing any external compressive devices or clothing

Maintaining affected extremities at the level of the heart to prevent hypoperfusion

Pain management initiated early

IV hydration and close monitoring of UOP for development of rhabdomyolysis

Special Considerations

Open fractures DO NOT exclude the possibility of compartment syndrome

Reversal or factor replacement should be considered for patients on anticoagulants, and factor replacement for patients with Hemophilia; Hematology should also be consulted for these patients (20)

In patients who are obtunded, cognitively impaired, intoxicated, or otherwise unable to give reliable history, there should be much lower threshold to check pressures when there are concerning physical exam findings or clinical suspicion

Consider this diagnosis in patients with increasing analgesic requirements who have had extremity trauma, injury, or recent surgery (18)

In patients who have borderline elevated compartment pressures with high clinical suspicion based on history / mechanism, consider hourly serial examinations to observe for increasing versus decreasing pressures (19)

For Information About:

Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

References

McQueen, Margaret & Gaston, Paul & Court-Brown, C.. (2000). Acute compartment syndrome: WHO IS AT RISK?. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British volume. 82-B. 200-203. 10.1302/0301-620X.82B2.0820200.

Via AG, Oliva F, Spoliti M, Maffulli N. Acute compartment syndrome. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2015;5(1):18-22. Published 2015 Mar 27.

Konstantakos EK, Dalstrom DJ, Nelles ME, Laughlin RT, Prayson MJ. Am Surg. 2007 Dec; 73(12):1199-209.

Osborn CPM, Schmidt AH, Management of Acute Compartment Syndrome. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2020 Feb 1

Perron AD, Brady WJ, Keats TE. Orthopedic pitfalls in the ED: acute compartment syndrome. Am J Emerg Med 2001;19:413-416. (Review)

Köstler W, Strohm PC, Südkamp NP. Acute compartment syndrome of the limb. Injury 2004;35(12):1221-1227 (Review)

Whitesides T, Haney T, Morimoto K, et al. Tissue pressure measurements as a determinant for the need of fasciotomy. Clin Orthop 1975;113:43-51.

Ulmer T. The clinical diagnosis of compartment syndrome of the lower leg: are clinical findings predictive of the disorder? J Orthop Trauma. 2002 Sep;16(8):572-7. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200209000-00006. PMID: 12352566.

Blue Chart Images: https://www.acepnow.com/article/tips-for-quickly-diagnosing-compartment-syndrome/2/

Tsai WH, Hunag ST, Liu WC. High risk of rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury after traumatic limb compartment syndrome. Ann Plast Surg.2015;74(suppl 2):S158–S161.

Lima RS, da Silva Junior GB, Liborio AB, et al. Acute kidney injury due to rhabdomyolysis. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2008;19(5):721-729.

Taylor RM, Sullivan MP, Mehta S. Acute compartment syndrome: obtaining diagnosis, providing treatment, and minimizing medicolegal risk. (2012) Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 5 (3): 206-13

Mühlbacher, J., Pauzenberger, R., Asenbaum, U. et al. Feasibility of ultrasound measurement in a human model of acute compartment syndrome. World J Emerg Surg14, 4 (2019).

Torlincasi AM, Lopez RA, Waseem M. Acute Compartment Syndrome. [Updated 2021 Jul 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan

McQueen MM, Duckworth AD, Aitken SA, et al. The estimated sensitivity and specificity of compartment pressure monitoring for acute compartment syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(8):673-677.

Large TM, Agel J, Holtzman DJ, et al. Interobserver variability in the measurement of lower leg compartment pressures. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(7):316-321.

Boody AR, Wongworawat MD. Accuracy in the measurement of compartment pressures: a comparison of three commonly used devices. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(11):2415-2422.

Schloss M, Weir TB, Jauregui JJ, Jazini E, Abzug JM. Increased morphine requirements are predictive of acute compartment syndrome in adults with tibia fractures. Int Orthop. 2020 Apr;44(4):743-752. doi: 10.1007/s00264-019-04455-2. Epub 2019 Dec 12.

Janzing, H. M., Broos, P. L. Routine monitoring of compartment pressure in patients with tibial fractures: Beware of overtreatment!. Injury 2001; 5: 415-21

Donaldson J, Goddard N. Compartment syndrome in patients with haemophilia. J Orthop. 2015;12(4):237-241. Published 2015 May 29. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2015.05.007

Authorship

Written by Tianna Negron, MD, PGY-1 University of Cincinnati Department of Emergency Medicine

Peer Review, Editing, and Posting by Jeffery Hill, MD MEd