Face the Music: Emergency Management of Facial Fractures

/ED Evaluation of Maxillofacial Trauma

Primary Survey

In the setting of maxillofacial trauma, airway compromise and severe hemorrhage are the most common life-threatening complications.

Ensuring airway patency is of the utmost importance in patients with maxillofacial trauma as up to 42% of patients with severe maxillofacial trauma require intubation. (4) Airway compromise most commonly occurs due to soiling of the airway (significant hemorrhage or emesis) and obstruction (posteriorly displaced tongue, soft tissue injury and swelling, or other foreign bodies such as dislodged teeth). (1,5)

When considering airway interventions, providers should anticipate difficulty in bag-mask ventilation as distorted facial anatomy can prevent adequate mask seal (particularly in Le Fort II and III fractures). (6) If bag-mask ventilation becomes difficult, consider using a supraglottic airway device as a bridge to a definitive airway.

Additionally, given high occurrence of soiled airways in maxillofacial trauma, providers must ensure multiple suction catheters (preferably large-bore DuCanto catheters) are at the ready and should consider advanced intubation methods such as Suction Assisted Laryngoscopy and Airway Decontamination (SALAD, discussed in further detail in this post). (7)

Lastly, it is important to consider optimal positioning of patients requiring airway intervention. Allowing patients to sit up can allow them to maintain their own airway and prevent aspiration of blood and emesis. (8,9) However, this is not always feasible as patients often must maintain spinal precautions during the initial stages of their evaluation. At minimum, cervical spinal precautions should be maintained as the incidence of cervical spinal injury associated with facial fractures ranges from 0.3 to 24.0%. (1,6,10)

Massive hemorrhage, significant enough to precipitate shock, can occur with maxillofacial trauma due to increased vascularity of facial structures. (5) Severe and life-threatening hemorrhage in maxillofacial trauma ranges has a reported incidence up to 11%. (5,11-13) Severe hemorrhage occurs most commonly in midfacial fractures with the maxillary artery and its intraosseous branches as the origin of bleeding. (1) Control hemorrhage early with direct pressure and early packing of the nasal and oral cavity as needed. (1,14,15) In particular, epistaxis in midfacial fractures can be controlled with posterior nasal packing with nasal tampons, Foley catheters, double lumen balloon catheters, or other nasal packing materials. (1,15) Life-threatening hemorrhage not controlled by these interventions may require emergent arterial ligation or embolization. (13,15,16)

Secondary Survey

Focused History - The following three screening questions can be used to help localize injuries:

How is your vision (blurriness, double vision, floaters or flashes of light, photophobia, foreign body sensation, pain with eye movements, etc.)?

Is your face numb?

Do your teeth fit together normally? (14)

All patients should also be asked about the use of anticoagulants or platelet-inhibiting medications. (8)

Inspection and Motor Function

Perform a thorough inspection of the face and oropharyngeal cavity with both a “bird’s eye view” from above and a “worm’s eye view” from below to evaluate for subtle facial asymmetries. Periorbital ecchymoses, or raccoon eyes, are associated with various injuries including basilar skull, nasoorbitoethmoid, Le Fort, orbital, and frontal bone fractures. (5,14)

Evaluate facial motor function by having the patient close their eyes tightly, raise their eyebrows, purse their lips, smile, and frown. It is particularly important to document facial nerve function with penetrating trauma to the lateral face.

Sensation, Palpation, and Stability

Assess for anesthesia due to injury of various branches of the trigeminal nerve by lightly touching the forehead, lower eyelid, cheek, upper lip, and chin. (14) The entire face should then be palpated in a systematic manner from top to bottom to assess for tenderness, step-offs, and subcutaneous crepitus (which may indicate sinus injury). (5) Facial stability is particularly important to assess with midface injuries and involves using one hand to rock the patient’s hard palate back and forth while the other hand palpates the central face. (5)

Ocular Examination

Thorough ocular examination is necessary as up to 6% of patients with maxillofacial trauma will develop vision loss. (15,17) Check visual acuity and pupillary response as vision loss or an afferent pupillary defect suggest injury to the optic nerve, retina, or globe. (8,14)

Teardrop-shaped pupils indicate an open globe injury whereas exophthalmos, fixed dilated pupils, ophthalmoplegia, and elevated intraocular pressures suggest retrobulbar hemorrhage and orbital compartment syndrome. (8,15,18)

Pain with extraocular movements may suggest occult periorbital fracture whereas limited extraocular movements (particularly inability to gaze upwards or downwards) is suggestive of extraocular muscle injury or entrapment. (1,5,10,14,15)

Finally, binocular diplopia is another finding suggestive of entrapment whereas monocular diplopia suggests lens dislocation, retinal detachment, or foreign body. (1,14,15)

Ears, Nose, and Oropharynx

Assess the ears for auricular hematoma, hemotympanum, or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak as these are indicative of a basilar skull fracture. Evaluate the nares closely for epistaxis, CSF leak, nasal lacerations, septal deviation, and nasal septal hematomas (which appear as a bulging, boggy, bluish-colored septal mass).(5,19)

Inspect the oropharyngeal cavity closely for malocclusion, any missing or fractured teeth, breaks in the oral mucosa, sublingual hematomas, or any evidence of alveolar ridge fractures. (14) The tongue blade test can be performed as a screening tool to identify mandibular fractures with sensitivity ranging from 85-95%. (20-22) This test (as demonstrated here) involves having the patient bite down on the tongue blade with the physician twisting the tongue blade in order to snap it. Patients who are able to maintain enough force such that the tongue blade snaps are unlikely to have a mandibular fracture whereas patients who cannot break the tongue blade require further imaging. (14)

Imaging

Facial CT imaging without contrast is the gold standard imaging modality for diagnosing facial fractures given its high sensitivity, low cost, and utility in surgical planning. (5,23) Patients with maxillofacial trauma often warrant CT imaging of their head and cervical spine due to mechanism of injury. While CT head has a sensitivity of 83-100% for detecting orbital, maxillary, and zygomatic fractures, it may not sufficiently delineate complicated fractures. (6,27-29) Finally, consider obtaining CTA imaging of the head and neck if there is penetrating trauma to the lateral face (particularly to the angle or ramus of the mandible given branches of the external carotid artery traverse this area).

Management and Disposition of Certain Fracture Types

Orbital and Nasoorbitoethmoid Fractures

OpenStax College, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The orbit is a four-walled structure with a posterior apex composed of the frontal bone superiorly, the zygoma and sphenoid bones laterally, the zygoma and maxilla inferiorly, and the ethmoid bone medially. (10,14,24) Orbital fractures are classified as pure or impure with pure (or blowout) fractures involving only the internal orbit without orbital rim involvement. (5,10) Orbital blowout fractures most commonly occur through the maxillary sinus (inferior wall) or through the thin-walled lamina papyracea of the ethmoid sinus (medial wall). (24) Nasoorbitoethmoid fractures occur when significant force is applied to the nasal bridge and often are accompanied by lacrimal duct injuries, disruption of the cribiform plate, dural tears, and traumatic brain injury. (5,14)

Management and timing of surgery for orbital fractures is controversial; as such, all orbital fractures necessitate consultation with facial surgery to discuss inpatient admission or to arrange for close outpatient follow-up. (5,14,24) Ocular involvement including visual field or acuity changes, optic nerve injury, extraocular muscle entrapment or injury, and globe rupture or laceration necessitate urgent facial surgery and ophthalmology consultation. (5,10,24) Concern for retrobulbar hemorrhage and orbital compartment syndrome necessitates emergent lateral canthotomy and ophthalmology evaluation. (5,14,24)

Nasoorbitoethmoid fractures generally require admission and consultation with facial surgery and neurosurgery. (5,14)

Isolated orbital blow-out fractures without ocular involvement (i.e., normal eye exam) may be discharged home and referred to facial surgery for repair in the 3-10 days. (24) These patients also require close outpatient follow-up with ophthalmology for a dilated eye exam within 48 hours to assess for unidentified retinal tears or detachments. (24) Recent research suggests antibiotic prophylaxis is not necessary for isolated, non-operative orbital fractures, though it was previously common practice for patients to be discharged home on cephalexin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, or clindamycin to cover for sinus pathogens (see Table 1 at the bottom of the post). (5,14,24,25)

Patients should also receive nasal decongestants and be counseled on sinus precautions (i.e., sneeze with your mouth open, no nose blowing, no smoking, avoid using straws, avoid air travel). (5,10,15)

Zygoma Fractures

The zygoma forms the inferior and lateral borders of the orbit and attaches to the maxillary, frontal, and temporal bones. Fractures through only the arch are termed zygomatic arch fracture whereas fractures through suture lines with adjacent bones are termed tripartite, tripod, or zygomaticomaxillary fractures. (5,10)

Patients with isolated, closed, minimally displaced zygomatic arch fractures can be discharged home with facial surgery follow-up and are often managed non-operatively. (5,10,14)

In contrast, complex zygomatic fractures that are open, comminuted, significantly displaced, or are associated with ocular injury require facial surgery consultation (and often ophthalmology consultation) with admission for repair and IV antibiotics (if open, see Table 1 below). (10,14)

Counsel patients to follow sinus precautions. (5)

Nasal Fractures

The nasal pyramid is composed of two bones that become progressively thinner as they project from the face. The majority of the nose’s structural integrity is provided by a cartilaginous framework, including the nasal septum. (10,19) Nasal fractures are diagnosed clinically and imaging is only necessary if there is concern for additional injuries. (5,10,19)

Closed, uncomplicated nasal fractures presenting immediately after injury, before significant swelling has occurred, can be reduced in the ED with ENT follow-up in 5-10 days. (5,19)

However, if swelling has distorted anatomical landmarks, closed reduction should be deferred until ENT follow-up. (5,19)

Closed nasal fractures with associated septal hematoma require hematoma drainage, bilateral nasal packing, prophylactic antibiotics (amoxicillin-clavulanate or clindamycin), and follow-up with ENT or the ED in 24 hours for packing removal. (5,19)

Any nasal fractures with external or internal lacerations near the site of the fracture should be considered open and require ENT consultation for repair and IV antibiotics (see Table 1 below). (10,26)

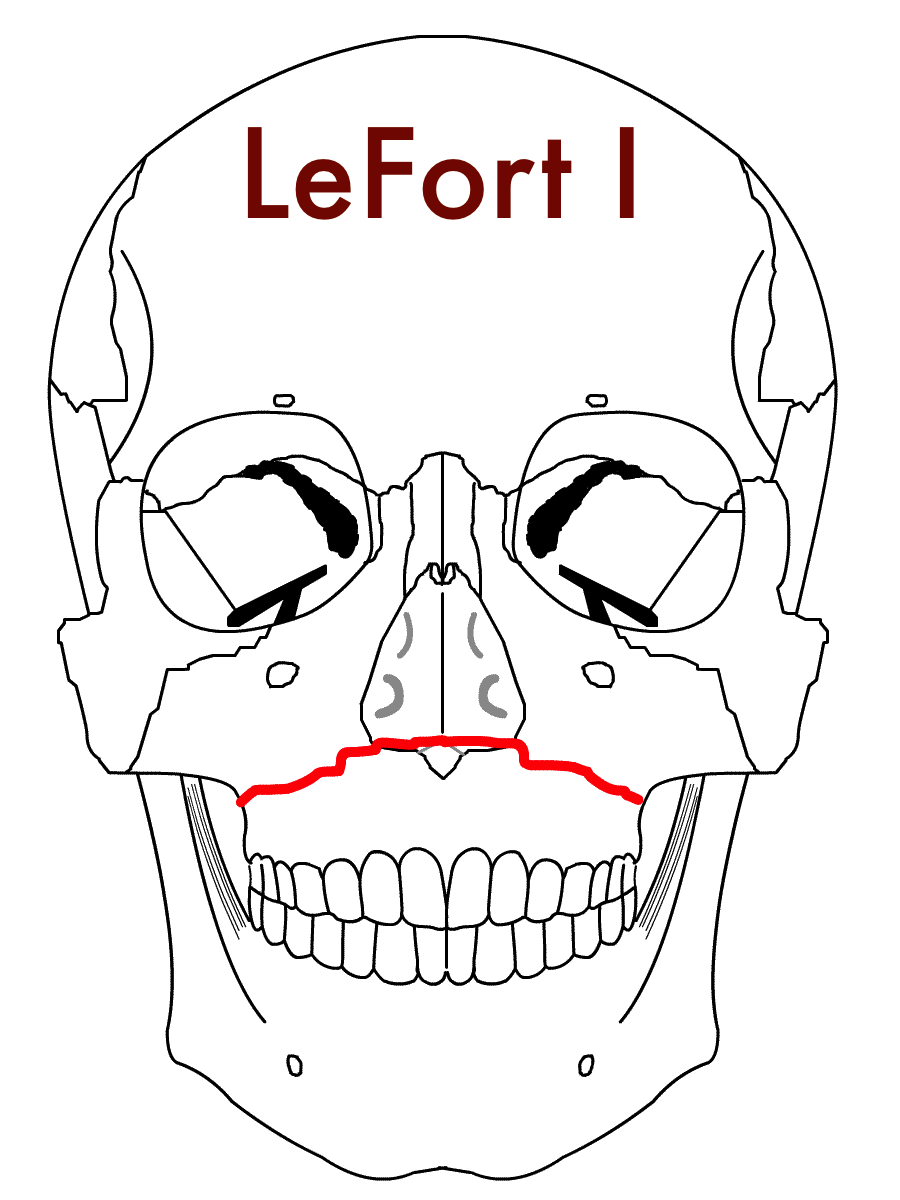

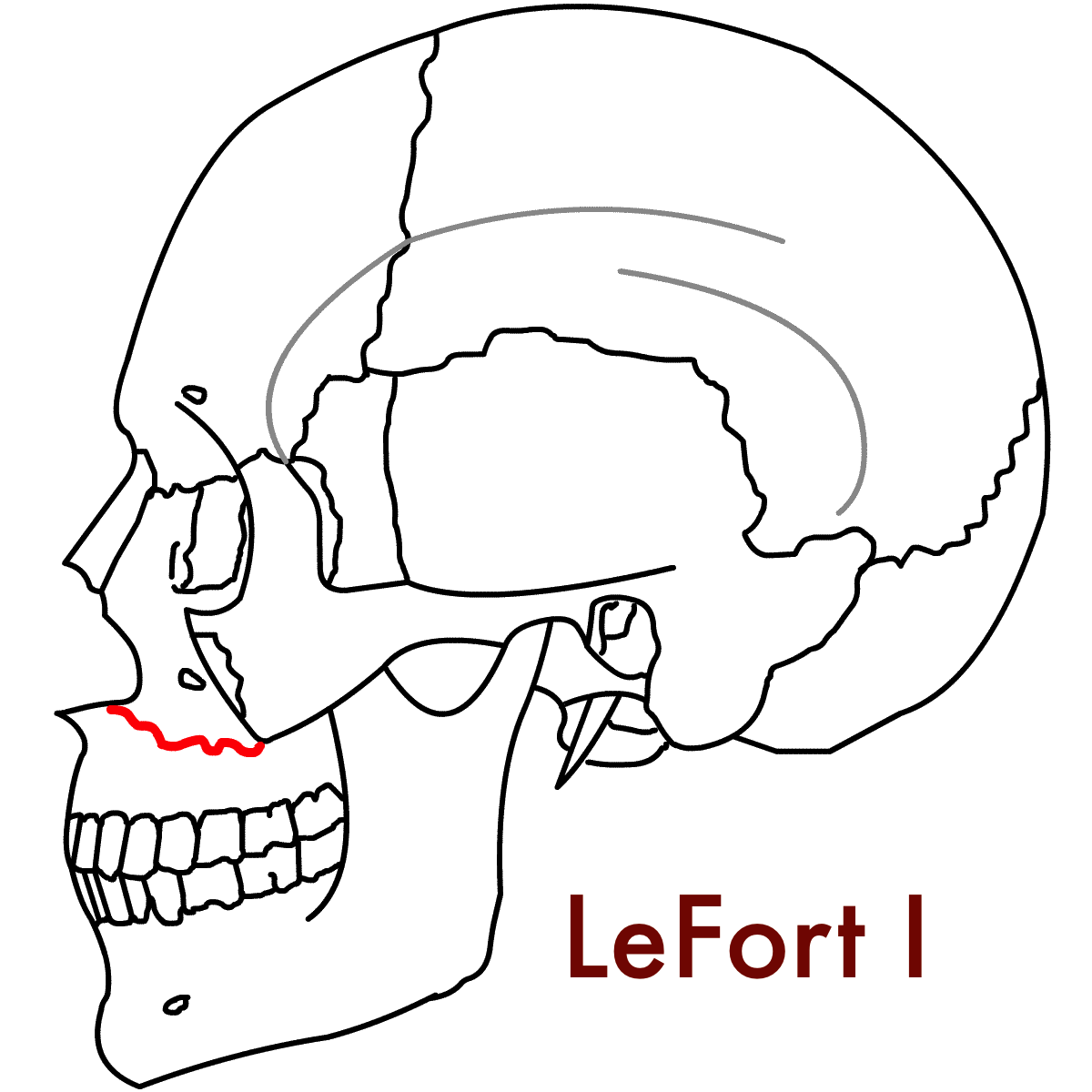

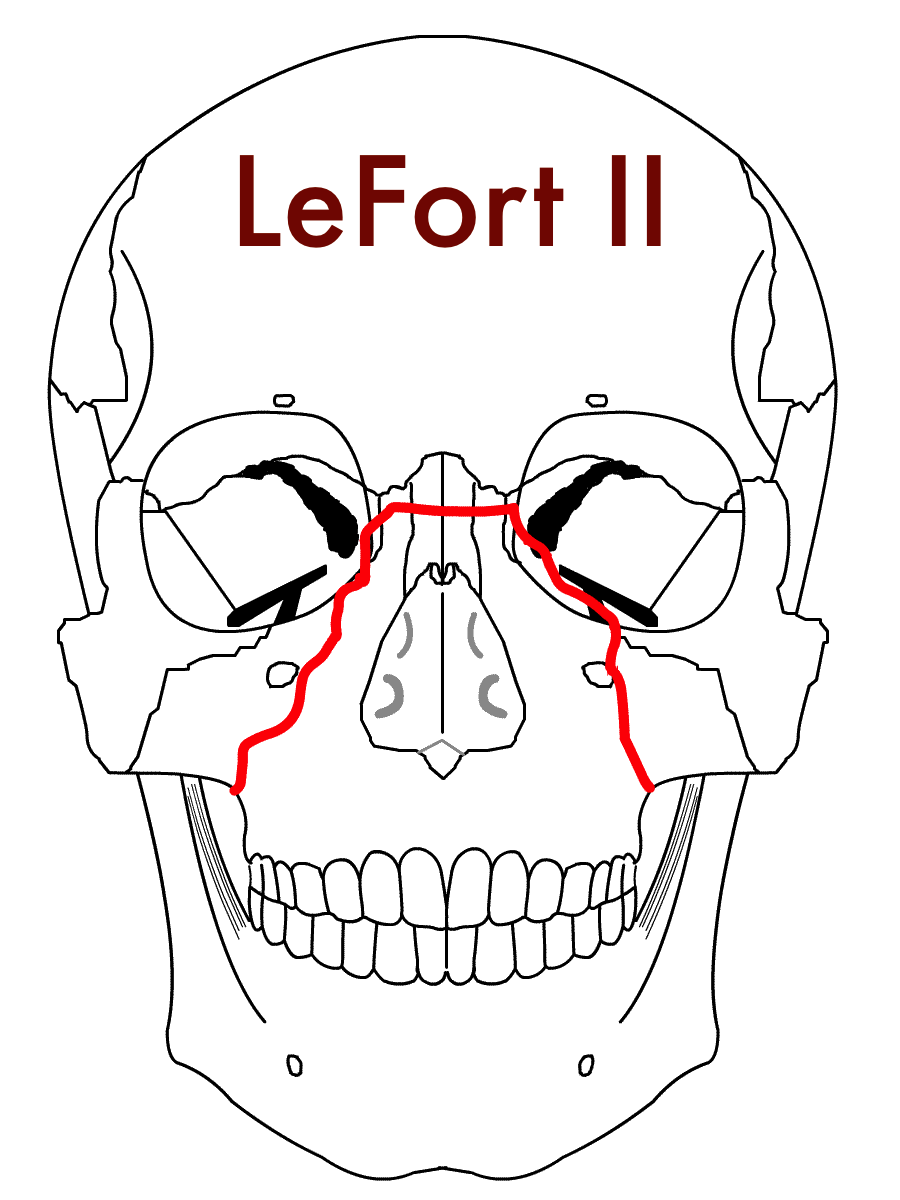

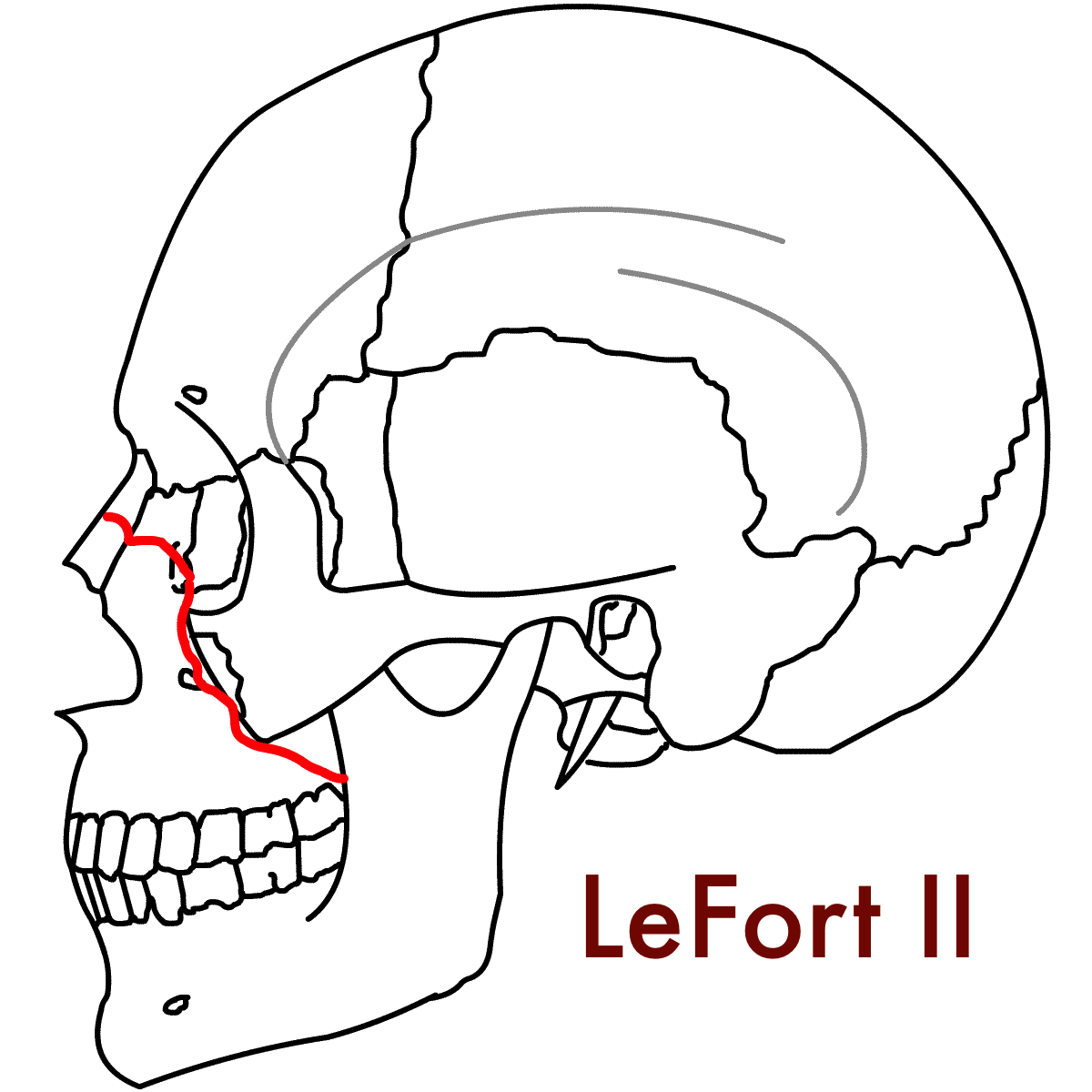

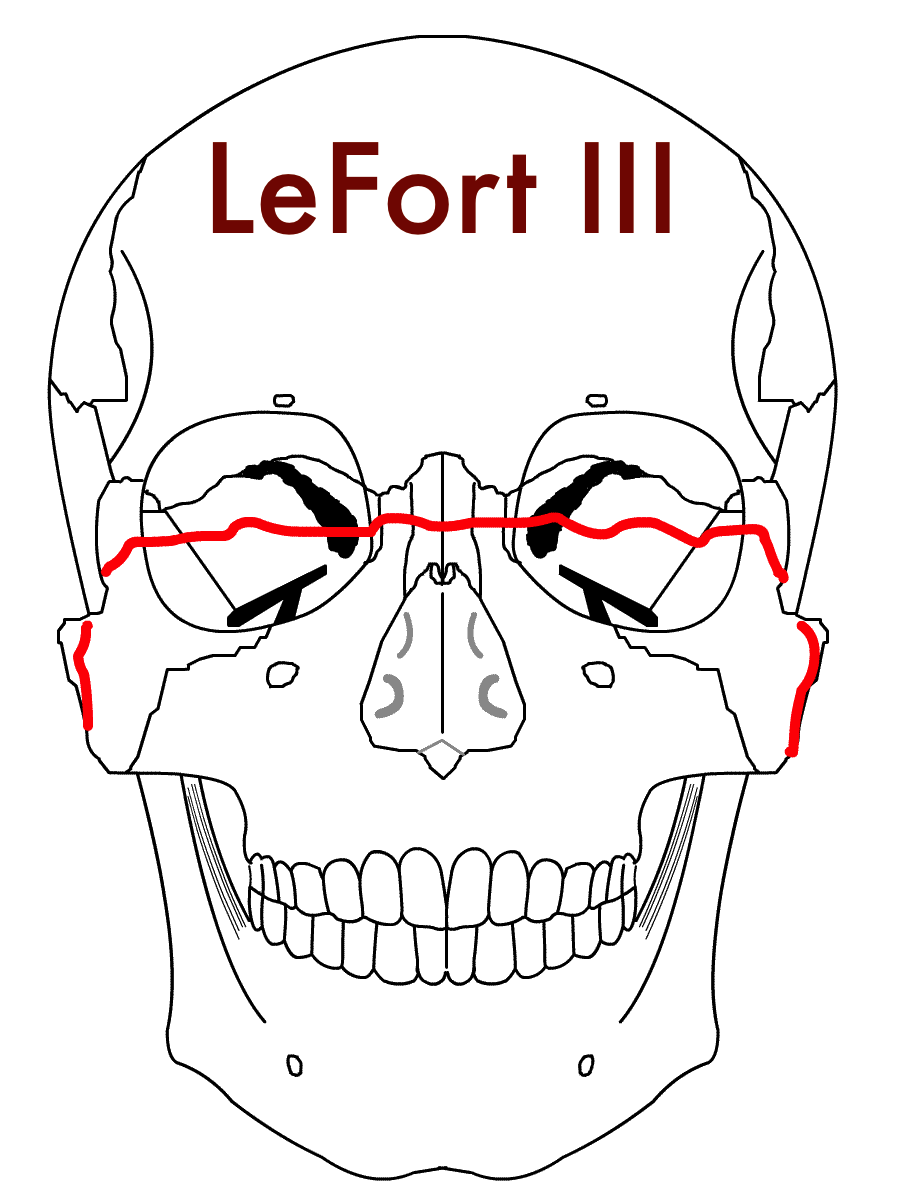

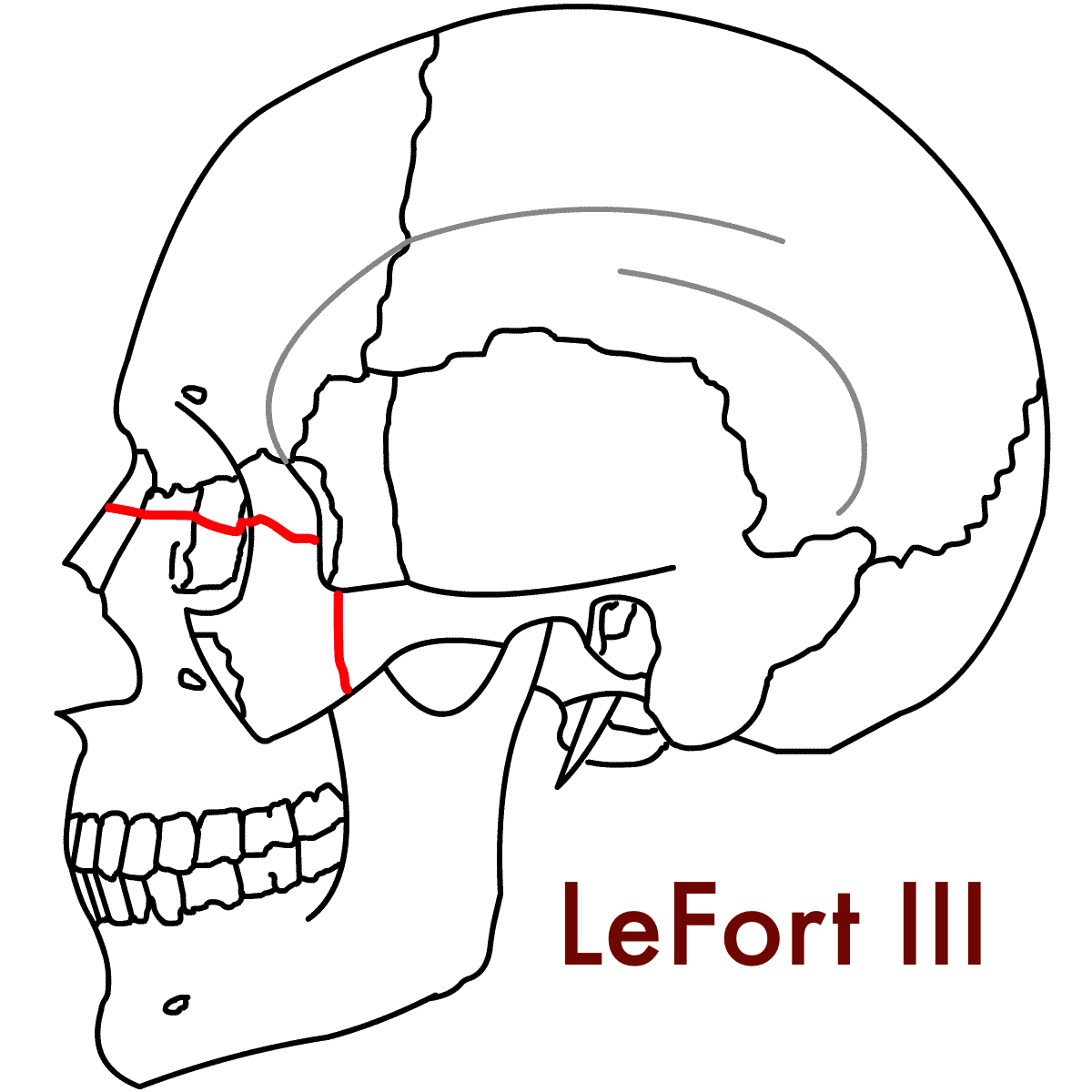

Maxillary (Le Fort) Fractures

The Le Fort maxillary fracture classification is named after the French surgeon, Rene Le Fort, who studied blunt facial trauma by inflicting trauma to cadaver heads through a variety of means (e.g., wooden clubs, cast iron rods, throwing heads against tables) although common lore holds that he primarily used cannonballs to inflict trauma. (27) All Le Fort fractures by definition involve the pterygoid plate, which is formed by thin, bony processes arising from the sphenoid bone.

Le Fort I fractures are transverse fractures that separate the maxilla from the pterygoid plate and nasal septum. (5,14) This leads to a “floating palate” wherein only the hard palate and teeth move, similar to a loose a denture.

Le Fort II fractures are pyramidal fractures that extend into the orbital floor and inferior orbital rim separating the central maxilla and hard palate from the rest of the face. (5,14) Le Fort II fractures result in movement of the hard palate and nose, but not the eyes. (14)

Le Fort III fractures, also known as craniofacial dysjunction, cause mobility of the entire face with the globes only held in place by the optic nerve and occur due to fractures of the frontozygomatic suture line, orbit, nose, and ethmoids. (5,14)

Le Fort IV fractures are Le Fort III fractures with frontal bone involvement. (5,14)

Le Fort injuries are associated with severe epistaxis and oropharyngeal hemorrhage often requiring airway protection in addition to nasal and oral packing to control bleeding. Facial surgery should be consulted early for Le Fort fractures with neurosurgical involvement for Le Fort IV fractures with intracranial extension. Isolated, stable Le Fort I or II fractures may be able to be discharged home with close follow-up after evaluation by facial surgery in the ED. However, most patients will require admission for IV antibiotics (if open to the skin or oropharynx, see table 1 below) and surgical repair. (5,10,14)

Mandible Fractures

OpenStax College, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Mandibular fractures most commonly occur at the mandibular condyle, body, and the angle. Due it is ring shape, the mandible is often broken in more than one location. (5) Mandibular fractures require careful intraoral examination as breaks in the oral mucosa indicate an open fracture. (14)

Open mandibular fractures require facial surgery consultation and admission for IV antibiotics (ampicillin/sulbactam, penicillin G, or clindamycin, see Table 1) and operative repair (5,14)

Closed mandibular fractures can be discharged home with referral for outpatient open reduction and internal fixation with facial surgery in 3-5 days, after swelling subsides. (5)

Patients discharged home with plan for delayed repair should be placed in a Barton’s bandage (ace wrap over the top of the head and underneath the mandible) on a soft or liquid diet. (5,14)

Table 1 - Recommendations for Management of Specific Fracture Patterns

References

Lynham AJ, Hirst JP, Cosson JA, Chapman PJ, McEniery P. Emergency department management of maxillofacial trauma. Emerg Med Australas EMA 2004;16(1):7–12.

Thaller SR, Beal SL. Maxillofacial trauma: a potentially fatal injury. Ann Plast Surg 1991;27(3):281–3

Erdmann D, Follmar KE, Debruijn M, et al. A retrospective analysis of facial fracture etiologies. Ann Plast Surg 2008;60(4):398–403.

Alvi A, Doherty T, Lewen G. Facial fractures and concomitant injuries in trauma patients. The Laryngoscope 2003;113(1):102–6.

Caputo ND. Maxillofacial Injuries. In: Harwood-Nuss’ Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine. New York, NY, USA: Wolters Kluwer; 2021. p. 161–9.

Caro DA, Bair AE. Airway Management for Blunt Facial Trauma. In: Management of the Difficult and Failed Airway. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill Education; 2018.

Root CW, Mitchell OJL, Brown R, et al. Suction Assisted Laryngoscopy and Airway Decontamination (SALAD): A technique for improved emergency airway management. Resusc Plus 2020;1–2:100005.

Perry M, Dancey A, Mireskandari K, Oakley P, Davies S, Cameron M. Emergency care in facial trauma--a maxillofacial and ophthalmic perspective. Injury 2005;36(8):875–96.

Perry M, Morris C. Advanced trauma life support (ATLS) and facial trauma: can one size fit all? Part 2: ATLS, maxillofacial injuries and airway management dilemmas. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008;37(4):309–20.

Boswell KA. Management of facial fractures. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2013;31(2):539–51.

Khanna S, Dagum AB. A critical review of the literature and an evidence-based approach for life-threatening hemorrhage in maxillofacial surgery. Ann Plast Surg 2012;69(4):474–8.

Shimoyama T, Kaneko T, Horie N. Initial management of massive oral bleeding after midfacial fracture. J Trauma 2003;54(2):332–6; discussion 336.

Bynoe RP, Kerwin AJ, Parker HH, et al. Maxillofacial injuries and life-threatening hemorrhage: treatment with transcatheter arterial embolization. J Trauma 2003;55(1):74–9.

Hedayati T, Amin D. Trauma to the Face. In: Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Sutdy Guide. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill Education; 2020. p. 1714–21.

DeAngelis AF, Barrowman RA, Harrod R, Nastri AL. Review article: Maxillofacial emergencies: Maxillofacial trauma. Emerg Med Australas EMA 2014;26(6):530–7.

Perry M, O’Hare J, Porter G. Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) and facial trauma: can one size fit all? Part 3: Hypovolaemia and facial injuries in the multiply injured patient. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008;37(5):405–14.

Dancey A, Perry M, Silva DC. Blindness after blunt facial trauma: are there any clinical clues to early recognition? J Trauma 2005;58(2):328–35.

Perry M, Moutray T. Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) and facial trauma: can one size fit all? Part 4: “can the patient see?” Timely diagnosis, dilemmas and pitfalls in the multiply injured, poorly responsive/unresponsive patient. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008;37(6):505–14.

McGinnis H. Nose and Sinuses. In: Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Sutdy Guide. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill Education; 2020. p. 1572–9.

Alonso LL, Purcell TB. Accuracy of the tongue blade test in patients with suspected mandibular fracture. J Emerg Med 1995;13(3):297–304.

Caputo ND, Raja A, Shields C, Menke N. Re-evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of the tongue blade test: still useful as a screening tool for mandibular fractures? J Emerg Med 2013;45(1):8–12.

Neiner J, Free R, Caldito G, Moore-Medlin T, Nathan C-A. Tongue Blade Bite Test Predicts Mandible Fractures. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Reconstr 2016;9(2):121–4.

Turner BG, Rhea JT, Thrall JH, Small AB, Novelline RA. Trends in the use of CT and radiography in the evaluation of facial trauma, 1992-2002: implications for current costs. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004;183(3):751–4.

Walker R, Adhikari S. Eye Emergencies. In: Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Sutdy Guide. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill Education; 2020. p. 1523–60.

Esce AR, Chavarri VM, Joshi AB, Meiklejohn DA. Evaluation of Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Acute Nonoperative Orbital Fractures. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2021;37(5):462–4.

Mondin V, Rinaldo A, Ferlito A. Management of nasal bone fractures. Am J Otolaryngol 2005;26(3):181–5.

Patterson R. The Le Fort fractures: René Le Fort and his work in anatomical pathology. Can J Surg J Can Chir 1991;34(2):183–4.