Diagnostics and Therapeutics: Vascular Access in the Emergency Department

/Establishing reliable vascular access is absolutely critical for ED patients requiring resuscitation, airway management, or medication administration. However, in at least 10% of patients, blind insertion of a peripheral IV may be unsuccessful for a variety of reasons including obesity, edema, IV drug use, surgical scars, dialysis, burns, and others (1,2). An alternative option is central access, but these procedures are time intensive and associated with their own unique set of risks and complications. In this post, we will review multiple alternative sites and techniques available for establishing peripheral access.

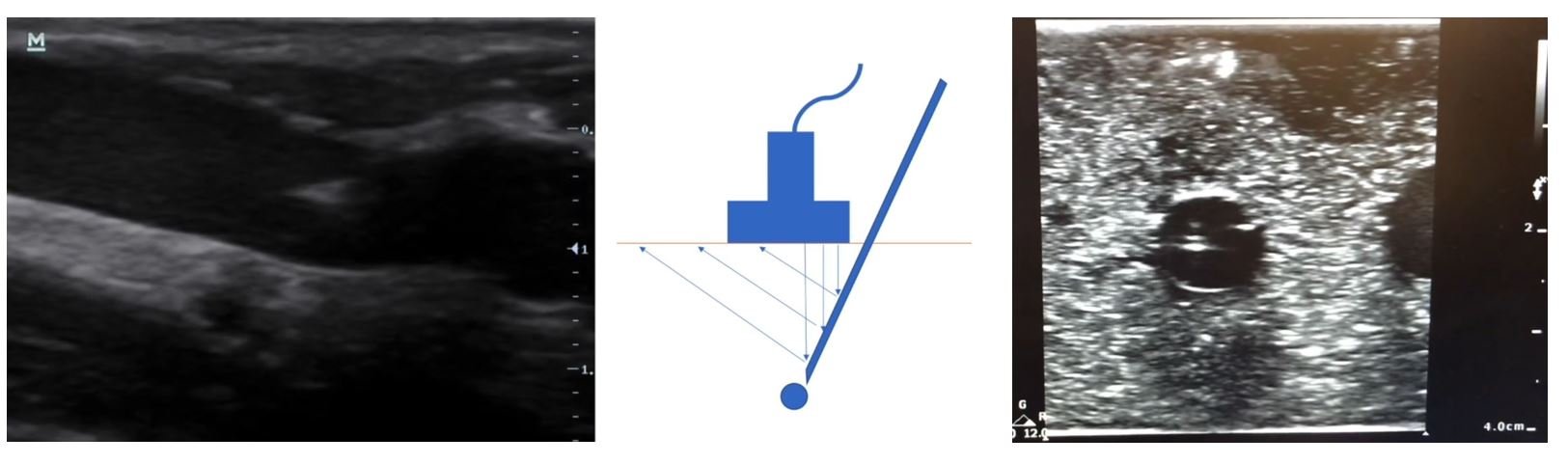

Ultrasound Guided Peripheral IV (USGIV) Access

Ultrasound allows us to visualize deeper, typically larger veins in the forearm and upper arm. The basilic and cephalic veins are common targets, though the deep brachial vein can also be used. This technique is an ideal second-line alternative when traditional palpation-based techniques fail. Contraindications for USGIV are the same as for any PIV: overlying skin infection, AV fistula in the extremity, previous surgery impacting vasculature, proximal trauma, or burns. Potential complications include paresthesias, brachial artery puncture, hematoma formation, loss of patency (3).

Technique

Position patient shoulder slightly abducted, elbow completely extended, forearm completely supinated. Place ultrasound machine on the opposite side of the bed to minimize neck strain.

Clean the linear ultrasound transducer or cover with a sterile tegaderm and apply sterile gel.

Apply a tourniquet proximal to the site.

Clean the skin just distal to the tourniquet with an antiseptic swab.

Use the linear ultrasound transducer to identify a thin-walled easily compressible vein and adjust the position/depth so that the vessel is in the center of the image.

Use a long (1.8 or 2.5 inch) catheter (4).

Insert the needle at a 30-45 degree angle approximately 1 cm distal to the ultrasound probe with the needle bevel angled upwards.

Do not move your ultrasound probe until you visualize your needle tip move into view.

Make small movements first advancing your probe and then advancing your needle until you visualize your needle tip in the vessel lumen.

Check for flash in the IV chamber.

Under ultrasound-guidance, continue to advance your needle an additional 1- cm in the vessel lumen.

Hold the needle in place and advance the catheter until hubbed at the skin.

Additional Resources

Two fantastic resources if you are a visual learner. The first is a video demonstrating normal technique for placement of USGIV’s and the second is a blog post from ALiEM discussing trouble-shooting techniques for difficult USGIV’s.

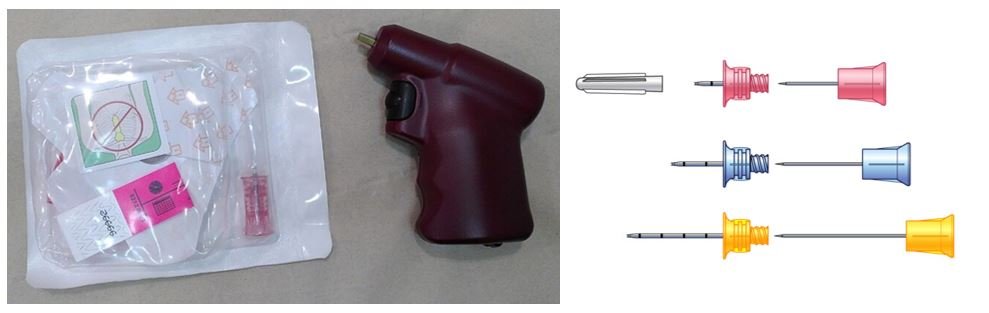

Intraosseous (IO) Access

IO access is an alternative option that is especially useful in emergency situations. IOs can be placed in under 20 seconds and are therefore the fastest method of obtaining vascular access of all the options described here (5). IOs are most commonly placed in the proximal tibia or humerus. An IO is a temporary solution and should be removed within 24 hours to avoid increased risk of infection such as osteomyelitis. Contraindications to placing an IO include a prior attempt at the same site, known orthopedic fracture or local hardware, overlying skin infection, and structural bone disease such as osteogenesis imperfecta (6).

IOs can be used both for resuscitation, medication administration, and for laboratory testing, but there are a few important considerations. First, IOs are extremely painful to the patient to run fluids through; thus, it is recommended to flush first with lidocaine. Second, flow rates through IO catheters vary widely by insertion site and may be slower than traditional intravenous routes (7,8). Specifically, one systematic review found that IO flow rates in the tibia can be as slow as 27-73 mL/min and IO flow rates in the humerus similarly slow at 16-84 mL/min, compared to traditional IV flow rates of 95 mL/min for an 18 gauge and 193 mL/min for a 16 gauge needle. However, use of a pressure bag has been found in several studies to increase those flow rates significantly — up to 69-165 mL/min through a tibia IO and up to 60-153 mL/min through a humerus IO (5).

Note that any medication given intravenously can also be given intraosseously, including vasoactive medications, contrast media, and blood products (8,9). Although the data is limited, intraosseous medication administration is considered pharmacokinetically equivalent to intravenous administration (10). For laboratory testing, it is important to be aware that not all values obtained via an intraosseous line correlate well with peripheral venous samples (11). For example, labs including WBC, platelets, serum CO2, sodium, potassium, calcium do not correlate with venous samples (11).

Technique

Sterilize the insertion site with povidone-iodine, chlorhexidine, or alcohol.

Use your nondominant hand to stabilize the arm or leg.

Using the EZ-IO, insert the IO needle perpendicular to the bone and advance the needle until you feel bony contact.

Drill through the bone, stopping once resistance suddenly decreases.

Unscrew and remove the stylet.

Apply a stabilizing dressing to the needle.

Connect extension tubing that has been pre-flushed with saline or lidocaine.

Slowly instill lidocaine into the intraosseous space.

Observe the area for signs of extravasation.

Additional Resources

Please see a previous Taming the SRU post for extra tips and trouble-shooting tricks, as well as a video demonstration for IO access.

External Jugular Vein (EJV) Access

The EJ vein is a great, often underutilized site for rapid peripheral IV access. EJs do not require ultrasound; however, they are dependent on the patient having favorable neck anatomy and easy to visualize landmarks. Due to their location, vasoactive medications and radiographic contrast should be administered with caution due to potential complications such as extravasation and airway compromise (12). Policies regarding EJ use for radiographic contrast may vary by institution. At our institution for example, EJs can be used for venous phase contrast studies but the physician must be present to monitor the patient throughout the study. EJs cannot be used for arterial phase studies as they require a faster contrast push.

Technique

Position the patient in Trendelenburg about 10-15 degrees. Turn head slightly away from side of EJ cannulation.

Cleanse the site with an antiseptic swab and use a finger to provide slight traction next to the vein to anchor it.

Approach the vein at a 5-10 degrees angle, about midway between the angle of the jaw and the clavicle.

After a blood flash return in the IV catheter [important note: you may not always see a flash with EJs when you are in the vessel lumen], advance the catheter until hubbed at the skin.

Connect pre-flushed extension tubing, ensure that blood draws back, then flush the tubing and apply a sterile dressing.

Secure the IV around the ear to prevent dislodgment.

Additional resources from ALiEM “Tricks of the Trade” - click on links to see videos

You can use your stethoscope as a “tourniquet” for EJ IV placement.

You can bend the angle of the angiocatheter if the jaw is in the way.

Have the patient hum if they cannot tolerate Trendelenberg to increase venous distention.

Peripheral Internal Jugular Vein (“Easy IJ”)

The Easy IJ is a great last resort when you have exhausted all other options for peripheral vascular access and you have been unsuccessful. This procedure involves placing a standard single lumen angiocatheter into the internal jugular vein. It is a relatively new procedure first described in 2009 (13). Since then, a handful of small prospective observational studies have been published demonstrating a high initial success rate of 88% with a mean procedure time of 5 minutes or less without major complications (14,15). Similar to peripheral EJs, vasoactive medications and radiographic contrast should be administered with caution and policies on this may vary by institution.

Technique

Position the patient in Trendelenburg about 10-15 degrees. Turn head slightly away from side of IJ cannulation.

Use the linear ultrasound probe to visualize the IJ.

Prep the area with chlorhexidine and place a small sterile drape over the area.

Cover linear probe with Tegaderm or sterile probe cover.

Using sterile jelly, once again visualize the IJ with ultrasound. Ask the patient to perform Valsalva maneuver.

Using a single lumen angiocatheter (studies have used varying sizes: 18-20 gauge, 4.8cm-6.35cm), puncture the skin at a 45-degree angle and advance needle into the IJ lumen.

Once flash is observed, advance the catheter into the lumen and withdraw the needle. Confirm placement with ultrasound.

Connect the pre-flushed extension tubing, ensure that blood draws back, then flush the tubing and apply sterile dressing.

Additional Resources

Also check out a great video created by the education team at EM:RAP for demonstration of the Easy IJ.

Post by Jessica Guillaume, MD

Dr. Guillaume is a PGY-1 in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati.

Editing by Tony Fabiano, MD and Anita Goel, MD

Dr. Fabiano is a PGY-4 in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati.

Dr. Goel is an Adjunct Assistant Professor in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati and an Assistant Editor of TamingtheSRU.

References

Jones SE, Nesper TP, Alcouloumre E. Prehospital intravenous line placement: A prospective study. Ann Emerg Med. 1989 Mar;18(3):244–6.

Egan G, Healy D, O’Neill H, Clarke-Moloney M, Grace PA, Walsh SR. Ultrasound guidance for difficult peripheral venous access: systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg Med J. 2013 Jul;30(7):521–6.

Presley B, Isenberg JD. Ultrasound-Guided Intravenous Access. StatPearls. 2023.

Bahl A, Hijazi M, Chen N-W, Lachapelle-Clavette L, Price J. Ultralong Versus Standard Long Peripheral Intravenous Catheters: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Ultrasonographically Guided Catheter Survival. Ann Emerg Med. 2020 Aug;76(2):134–42.

Ngo AS-Y, Oh JJ, Chen Y, Yong D, Ong MEH. Intraosseous vascular access in adults using the EZ-IO in an emergency department. Int J Emerg Med. 2009 Sep 11;2(3):155–60.

Luck RP, Haines C, Mull CC. Intraosseous Access. J Emerg Med. 2010 Oct;39(4):468–75.

Pasley J, Miller CHT, DuBose JJ, Shackelford SA, Fang R, Boswell K, et al. Intraosseous infusion rates under high pressure. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015 Feb;78(2):295–9.

Petitpas F, Guenezan J, Vendeuvre T, Scepi M, Oriot D, Mimoz O. Use of intra-osseous access in adults: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2016 Dec 14;20(1):102.

Schindler P, Helfen A, Wildgruber M, Heindel W, Schülke C, Masthoff M. Intraosseous contrast administration for emergency computed tomography: A case-control study. Li Y, editor. PLoS One. 2019 May 31;14(5):e0217629.

Von Hoff DD, Kuhn JG, Burris HA, Miller LJ. Does intraosseous equal intravenous? A pharmacokinetic study. Am J Emerg Med. 2008 Jan;26(1):31–8.

Miller LJ, Philbeck TE, Montez D, Spadaccini CJ. A New Study of Intraosseous Blood for Laboratory Analysis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010 Sep 1;134(9):1253–60.

McDonald JS, Schmitz JJ, Mendes BC, McDonald RJ. Airway compromise following contrast extravasation from an external jugular intravenous line. Radiol Case Reports. 2024 Jan;19(1):58–61.

Moayedi S. Ultrasound-Guided Venous Access with a Single Lumen Catheter into the Internal Jugular Vein. J Emerg Med. 2009 Nov;37(4):419.

Kiefer D, Keller SM, Weekes A. Prospective evaluation of ultrasound-guided short catheter placement in internal jugular veins of difficult venous access patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2016 Mar;34(3):578–81.

Moayedi S, Witting M, Pirotte M. Safety and Efficacy of the “Easy Internal Jugular (IJ)”: An Approach to Difficult Intravenous Access. J Emerg Med. 2016 Dec;51(6):636–42.

Gonzalez R, Cassaro S. Percutaneous Central Catheter. StatPearls. 2023.