Diagnostics: Thromboembolic Disease in Pregnancy

/Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the number one cause of mortality in pregnant patients, and therefore it is critical for emergency physicians to understand how to appropriately work up and manage this condition. The diagnostic pathway has key differences from the general population given the risks of radiation to the fetus and the physiologic changes associated with pregnancy that naturally make these patients higher risk. In addition to discussing the diagnostic pathway and how it differs in pregnancy, we will discuss the treatment options available to both unstable and stable patients during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy

VTE is not only important to understand because it is the number one cause of mortality for pregnant patients, but also because it is common and will show up in your Emergency Department likely frequently throughout your career. It is estimated to affect every 1 in 500 to 2000 pregnancies. The incidence of disease is 4-50 times higher than the general non-pregnant population. According to a CDC study, VTE contributes to 10.5% of all pregnancy-related deaths. The risk of VTE is not evenly distributed throughout pregnancy, and has its highest incidence in the first six weeks postpartum. During pregnancy the risk peaks during the first trimester with its lowest risk during the second trimester, however, this has been widely disputed in the literature.

Physiologic Changes of Pregnancy

There are physiologic changes that occur during pregnancy that inherently increase patients risk for VTE. We all recall Virchow’s triad as: 1) venous stasis, 2) hypercoagulability, and 3) endothelial injury. Each of these aspects of the triad are affected during pregnancy increasing the pro-thrombotic state of pregnant patients. Venous stasis is increased in a multitude of ways including a drastic increase in blood volume throughout pregnancy (the plasma volume increases by as much as 40-50% from the pre-pregnancy volume). The increase in blood volume leads to increased stretching of the blood vessels which leads to valvular incompetence and blood pooling, particularly in the legs. As a pregnancy progresses, the gravid uterus compresses the pelvic blood vessels, decreasing flow and increasing dilation and pooling again particularly in the legs. Endothelial injury is also increased (specifically during the delivery), with certain delivery methods increasing the risk further including: c-sections, vacuum assisted delivery, and the use of forceps. Lastly, pregnancy increases the hypercoagulable state of a pregnant person by increasing pro-coagulation factors I, II, VII, VIII, IX, X, and decreasing anti-thrombotic factors like Protein S.

Deep Vein Thrombosis Diagnosis in the Pregnant Patient

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is the first of two diagnoses that falls under the VTE umbrella discussed in this post. The presentation of symptoms of DVT in pregnancy remains similar to the general population. Symptoms include: diffuse unilateral leg swelling, pain, erythema, and warmth (see image for example). Any one or combination of these symptoms should raise suspicion of DVT on your differential diagnosis. In pregnancy it is important to note that there is an increased incidence in the left lower extremity compared to right lower extremity for DVTs. Studies for first time DVT in pregnant patients have identified a predilection for left-sided first-time DVT anywhere from 88-97% of the time at diagnosis. This is due to anatomical changes from the gravid uterus as mentioned above, as the left iliac vein tends to be more compressed than the right iliac vein due to the overlying right iliac artery (see image for reference).

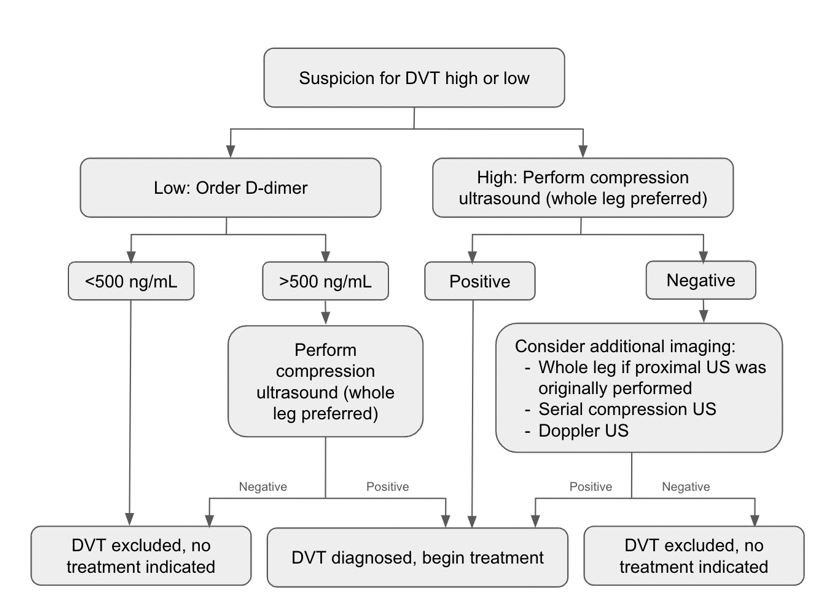

Pregnant and postpartum patients are intrinsically high-risk, and because of this status, not eligible for Well’s Criteria for DVT. This is the first major difference between the general population and the pregnant patient. However, we are not without guidelines to help us! The first step is to use your own clinical gestalt to determine if the patient is high-risk or low-risk for DVT. If you feel the patient is high-risk (ie. history of VTE, increased calf circumference, pain and swelling), then the next step is to attain a compressible ultrasound of the affected leg. Whole leg ultrasonography is ideal, however, proximal vein (without calf imaging) is also acceptable for first-line imaging. If a clot is found, then the diagnosis is made and treatment can begin (discussed separately). However, if clinical suspicion is high enough, doppler ultrasound, MR venography, or serial compressive ultrasound imaging can all be considered. These options should be tailored to the individual patient including whether or not to begin empiric anticoagulation.

The trickier patient to appropriately workup and diagnose is the patient in which you have a “low” suspicion for DVT, but the diagnosis is still on your differential. In 2009, a cross-sectional research study of pregnant patients with suspected DVT were evaluated, and used to derive three symptoms that are highly predictive of DVT in pregnancy (Left leg symptoms, >2 cm calf circumference difference or Edema, and First trimester onset) called the LEFt clinical decision tool. If none of these symptoms were present, the likelihood of a DVT was extremely unlikely. While available, this tool is limited without many externally validating studies. So what are you supposed to do?

Use of a d-dimer is often the next appropriate step. A cut-off of 500 ng/mL on the high-sensitivity assay is the recommended level to safely rule out DVT in pregnancy. In other words, in the pregnant patient whom you have low-suspicion for DVT and a D-dimer level less than 500 ng/mL, no further imaging or workup is needed. If the D-dimer is greater than 500 ng/mL, the next most appropriate step is to do whole-leg compression ultrasonography. It should be noted in that the D-dimer experiences a physiological rise throughout pregnancy, peaking in the third-trimester, making it difficult to accurately interpret sometimes.

These pathways are also diagrammed here for your ease of use.

Pulmonary Embolism Diagnosis in the Pregnant Patient

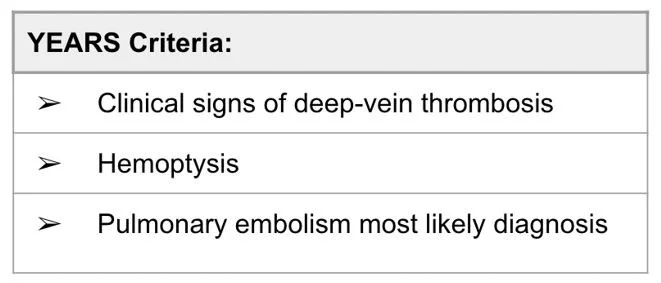

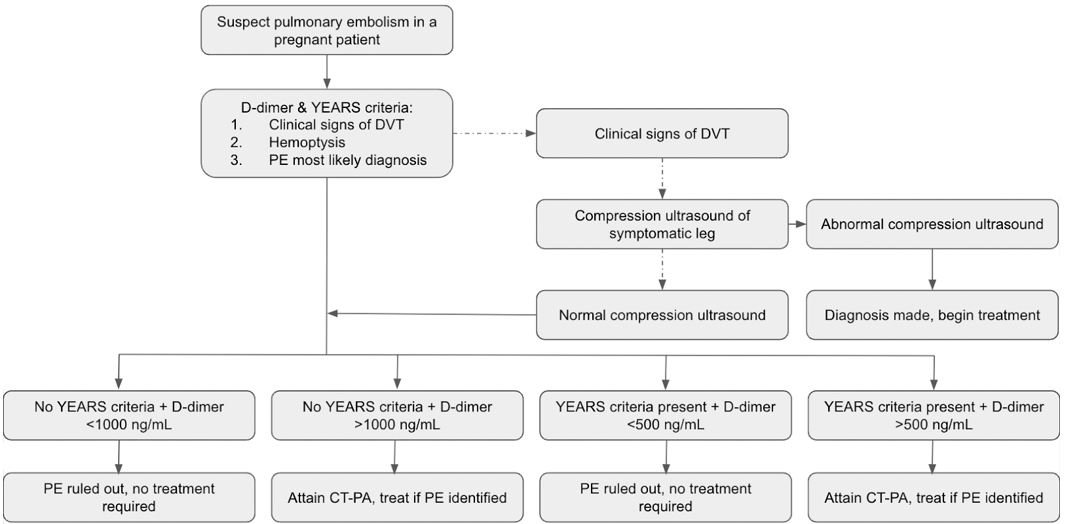

As discussed above, pulmonary embolism (PE) is a can’t-miss diagnosis of pregnancy because of the high mortality association. This is not a straight-forward diagnosis, however, because the symptoms of PE are often mimicked by the normal physiologic changes of pregnancy. Presenting signs and symptoms include: dyspnea, chest pain, tachycardia, hypoxia, and signs/symptoms of DVT as discussed above. Research has borne-out that we are poor at determining who is appropriate for further workup of PE and who is experiencing normal symptoms of pregnancy because less than five percent of patients suspected to have PE are actually diagnosed with the condition, compared to 15-20% of patients in the general population. This clinical quandary has led to the development of pregnancy adapted YEARS criteria in an attempt to better categorize who is high-risk for PE, and for whom radiation can be safely avoided .

A prospective study was conducted evaluating a total of 510 pregnant women suspected of having a PE. Twenty were diagnosed with PE at their initial presentation. One patient was diagnosed with a popliteal DVT at follow-up, and zero patients diagnosed with PE at follow-up. CT-Pulmonary Angiography (CT-PA) was not indicated per the protocol and safely avoided in 195 patients (35% of patients). The algorithm was most successful in avoiding radiation in the first-trimester, avoiding 65% of patients who presented in this time-window compared to the patients who presented in the third-trimester, 32%.

The YEARS algorithm for diagnosing PE in the pregnant patient uses the combination of the three criteria in the table in addition to use of a D-dimer, and ultrasound. In a patient with symptoms suspicious for PE, a D-dimer is ordered and the criteria evaluated. If clinical symptoms of a DVT are present, then compressive ultrasonography is undergone. If a DVT is present, then the diagnosis is complete and the patient is started on therapeutic anticoagulation. If there are no DVT symptoms or the compressive ultrasound is normal, then the D-dimer is utilized. Here there is a key departure from the DVT algorithm discussed above, as the cut-off level for the D-dimer is adjusted based upon whether or not YEARS criteria are present (see algorithm below). The two populations who would move on through the algorithm to undergo CT-PA are 1) those with zero criteria met but a d-dimer of >1000 ng/mL and 2) those with at least one criteria met and a d-dimer of 500 ng/mL. Therapeutic anticoagulation is discussed later in the management section.

A pregnancy adapted YEARS Algorithm is diagrammed here for your ease of use.

Management Options for venous thromboembolism in Pregnancy

Anticoagulation. Anticoagulation. Anticoagulation.

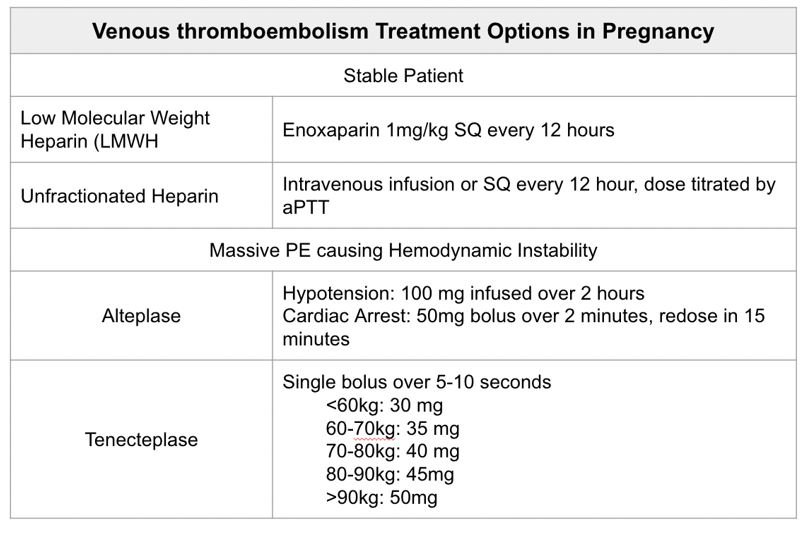

The mainstay of treatment for VTE in pregnant patients is anticoagulation. Just like any other medication, emergency physicians must be careful in selecting an appropriate anticoagulation regimen for their patient. Some options are strict no-no’s. Warfarin has been proven to be unsafe in pregnancy as it crosses the placenta, is a known teratogen, and causes both fetal and maternal bleeding. Additionally, direct-oral anticoagulants (DOACs), such as apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban are avoided as they have not yet been studied thoroughly.

Low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs) are the first-line choice for management of VTE in pregnancy. The chart to the right outlines the doses and routes available. LMWHs have been shown to be safe in pregnancy, as they do not cross the placenta. Unfractionated heparin (UFH) is also an option, however, has more side effects than its counterpart (ie. increase risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia). UFH may be more appropriate in the patient who is nearing birth and needs a short on/off time. Lastly, UFH is the preferred anticoagulant for the pregnant patient with kidney disease as LMWH is renally cleared.

Treatment duration is debated and varies depending on the time of VTE diagnosis. Patients should remain on anticoagulation for at least three months. However, the duration should be extended to include the remainder of the pregnancy and six weeks postpartum. The risk of VTE is highest in the first six weeks postpartum, and is thus very important to continue anticoagulation through this period.

In the patient with a massive-PE causing hemodynamic instability the treatment is the same as far the non-pregnant patient — t-PA. The contraindications are the same as for the non-pregnant patient including: prior ICH, known brain lesion/malignancy, ischemic stroke in the past three months, suspected aortic dissection, active bleeding, and closed head trauma in the past three months.

post by allison zinter, md

Dr Zinter is a PGY-1 in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati.

editing by megan wright, md and anita goel, md

Dr Wright is a PGY-4 in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati and a senior resident director of the Medical Student Scholars Program, with plans to do a fellowship in education simulation next year.

Dr Goel is an Adjunct Assistant Professor in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati and an Assistant Editor of TamingtheSRU. She is a graduate from the UC EM residency, class of 2018.

references

Mulhotra, A. MD, Weinberger, S. MD. Venous thromboembolism in pregnancy: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. UpToDate. Retrieved September 14, 2024, from https://www-uptodate-com.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/contents/venous-thromboembolism-in-pregnancy-epidemiology-pathogenesis-and-risk-factors?search=vte%20in%20pregnancy&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2%7E150&usage_type=default&display_rank=2#H982202608.

Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm#trends (Accessed on September 14, 2024.

Soma-Pillay P, Nelson-Piercy C, Tolppanen H, Mebazaa A. Physiological changes in pregnancy. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2016 Mar-Apr;27(2):89-94. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2016-021. PMID: 27213856; PMCID: PMC4928162.

Madsread. (2016). WikiMedia Commons [Digital Image]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Deep_Vein_Thrombosis_of_the_leg._.jpg

Mulhotra, A. MD, Weinberger, S. MD. Initial evaluation of DVT in pregnancy and postpartum: alternate approach. UpToDate. Retrieved September 14, 2024 from https://www-uptodate-com.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/contents/image?imageKey=PULM%2F144535&topicKey=PULM%2F1349&search=vte%20in%20pregnancy&source=see_link

Righini M, Jobic C, Boehlen F, Broussaud J, Becker F, Jaffrelot M, Blondon M, Guias B, Le Gal G; EDVIGE study group. Predicting deep venous thrombosis in pregnancy: external validation of the LEFT clinical prediction rule. Haematologica. 2013 Apr;98(4):545-8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.072009. Epub 2012 Oct 12. PMID: 23065510; PMCID: PMC3659985.

Van Der Pol, L. M., Tromeur, C., Bistervels, I. M., Ni Ainle, F., Van Bemmel, T., Bertoletti, L., & Huisman, M. V. (2019). Pregnancy-adapted YEARS algorithm for diagnosis of suspected pulmonary embolism. New England Journal of Medicine, 380(12), 1139-1149.

Mulhotra, A. MD, Weinberger, S. MD. Venous thromboembolism in pregnancy and postpartum: Treatment. UpToDate. Retrieved on September 14, 2024 from https://www-uptodate-com.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/contents/warfarin-drug-information?search=vte%20in%20pregnancy&topicRef=1350&source=see_link#F234856