Diagnostics and Therapeutics: Tricks of the Trach

/A tracheostomy (trach) is a surgical or percutaneous procedure that creates a temporary or permanent airway by creating an opening in the anterior neck directly into the trachea. It is performed to bypass upper airway obstruction or to take the place of an endotracheal tube when prolonged mechanical ventilation or airway management is needed (1). While there are several short- and long-term complications associated with tracheostomies, there are few true tracheostomy emergencies.

In this post, we will cover tracheostomy basics and three categories of tracheostomy emergencies including accidental decannulation, obstruction, and hemorrhage. We will discuss strategies for managing these emergencies in both the academic and community emergency department settings.

Anatomy

A tracheostomy is a surgical opening in the anterior neck which is used for placement of a semi-permanent or permanent airway. Tracheostomies differ from cricothyroidotomies because the opening is usually planned and made by a surgeon below the level of the cricoid cartilage rather than a more emergency procedure performed by an emergency physician or a surgeon above the level of the cricoid cartilage. A tracheostomy is ideally placed between the second and third tracheal rings which is about halfway between the cricoid cartilage and sternal notch (2). This location decreases the risk of later complications including trachea-innominate fistula and subglottic stenosis (3). Tracheostomies can be performed for a number of indications, including prolonged dependence on a ventilator for breathing as well as bypassing an obstructed upper airway. The indication for a patient’s tracheostomy is important to identify early in the course of a patient’s ER stay as troubleshooting techniques may differ for different tracheostomy indications, as detailed below.

Nuts and Bolts (aka the basics)

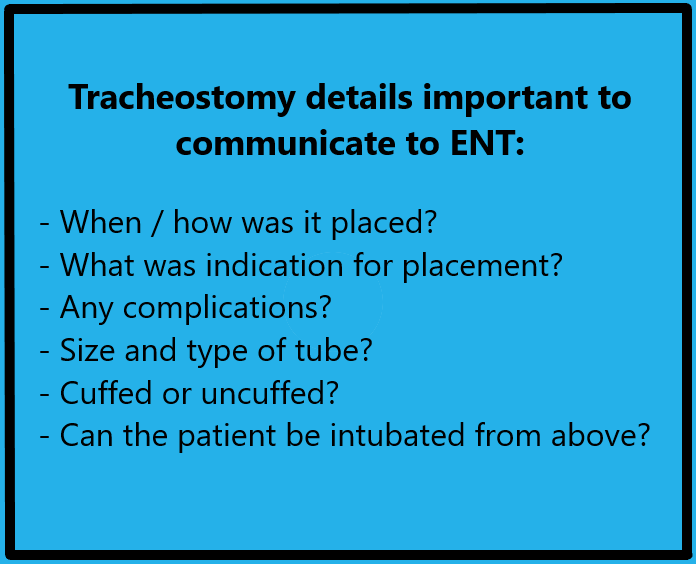

Tracheostomy tubes come in several shapes and sizes as different types serve different purposes depending on the indication for the tracheostomy and patient factors. For this reason, it is imperative to obtain a detailed history of the type of tracheostomy tube a patient has and, if possible, details surrounding the individual patient factors and airway anatomy. Different brands may have different inner cannula diameters and lengths for a given size trach, so it is important to know which brand a patient uses if possible (2).

A normal tracheostomy tube is composed of the outer cannula (A) with flange (B), cuff (C), and pilot balloon (D) as well as the inner cannula (E) and obturator (F), as seen and labeled in the diagram above. Possible variations to this set up include a tracheostomy tube without a cuff and/or without an inner cannula. The obturator assists with placement of the tracheostomy tube and does not remain in place while the trach is functional.

Single vs Dual Lumen: Dual lumen tracheostomy tubes are most common as this allows the inner cannula to be removed to aid with tracheostomy hygiene and suctioning without having to remove the entire airway adjunct itself. A single lumen tracheostomy may be used if a patient has extensive secretion burden or need for frequent bronchoscopy whereby the inner cannula is too narrow to adequately allow for clearance of secretions via suctioning or bronchoscopy (2).

T Tubes: A T-tube is a special T shaped trach tube used in patients with subglottic stenosis or tracheomalacia that acts as a tracheal stent in addition to an airway (3).

Cuffed vs Uncuffed: From the emergency medicine perspective, it is important to remember that patients who require mechanical ventilation need cuffed tracheostomy tubes. If a patient typically has an uncuffed tracheostomy and breathes spontaneously but decompensates and requires mechanical ventilation, the tube will need to be exchanged prior to the initiation of mechanical ventilation. Uncuffed tubes allow for easier phonation and have a lower risk of long-term complications associated with pressure injury to the trachea from an inflated cuff (2).

Tracheostomy Emergencies

1) Accidental Decannulation

Accidental decannulation refers to the unplanned removal of the tracheostomy tube from the neck and is noted in about 1% of tracheostomies overall (4). One prospective analysis found an accidental decannulation rate of 13% within the first year of placement (5). This may occur with improper security of the tube, position changes, or patient factors such as altered mental status or distress (6). Two essential pieces of information that direct management are:

How old is the tracheostomy?

How long has it been dislodged?

Tracheostomies take approximately one week to mature, however percutaneous tracheostomies may take up to 14 days (4). Early decannulation of an immature tracheostomy (7-10 days old) is an absolute contraindication for replacement by the emergency physician. The risk of replacing an immature tracheostomy is creating a false tract in the anterior passage of the neck which may lead to pneumothorax, subcutaneous emphysema, and/or perforating the posterior tracheal wall (4). Hypoxia and death may also result from loss of the airway itself. For this reason, ENT should be called. If ENT is not immediately available, such as in the community setting, and if the patient requires mechanical ventilation, endotracheal intubation should be performed, and the patient should be transferred for ENT evaluation once stable. Alternatively, the patient can be bagged using bag-valve-mask to the mouth while covering the stoma (1).

Accidental decannulation of a mature tracheostomy tube (>10 days old or after confirmation of easy trach exchange by ENT) could potentially be managed by the emergency physician. It is critical to know how long the tube has been dislodged. Tracts begin to close as early as a few hours after decannulation, and after 3-4 days, typically the tract is closed completely (7). If the tube has only been dislodged for a short period of time, a tracheostomy exchange in the ED is reasonable. Either using the same size tube or one size down, attempt replacement of the tube itself. You can preload the new tracheostomy tube onto a fiberoptic scope, visualize and confirm with video the tract into the trachea, and then place tracheostomy into the stoma (2,4). This can be especially helpful in newer tracheostomies with higher risk of false tract creation or if you are in the community with fewer resources and / or lack of specialist presence.

If tracheostomy tubes are unavailable, endotracheal tubes may be used in the tracheostomy site. If unsuccessful, after checking anatomy, intubate orally with plans for tracheostomy replacement by ENT (1).

*A Note on Laryngectomy Patients*

Patients with laryngectomies pose a unique challenge from an airway management standpoint because unlike patients with tracheostomies, these patients’ airways are NOT contiguous with their nose or mouth. Therefore, they CANNOT be intubated nasally or orally in the setting of issues with their stoma.

2) Obstruction

Obstruction of the tracheostomy tube can occur at any time after a tracheostomy is performed. It is reported in approximately 3.5% of tracheostomies and makes up about 14% of catastrophic tracheostomy emergencies (4,6). Copious or thick secretions, clotted blood, or other foreign bodies can obstruct the small opening in the tracheostomy tube which can manifest as acute respiratory distress, hypoxia, or apnea. Increased secretion burden may result from infection, aspiration, or inadequate airway clearance/tracheostomy care. If obstruction is suspected, the following steps are a reasonable guide for troubleshooting (1):

Remove obstructing devices from the tracheostomy tube itself (speaking valve, inner cannula)

Deflate the cuff if present

Clean the inner cannula and attempt to pass a suction catheter through the tracheostomy

Suction to attempt to clear the obstruction

If unable to clear, remove entire tracheostomy tube and bag-mask-ventilate patient

Attempt replacement of tracheostomy tube

If unable, perform endotracheal intubation and/or place supraglottic airway

If unable to endotracheally intubate, attempt intubation of stoma using smaller tube or bougie

Ultimately may require therapeutic bronchoscopy

3) Hemorrhage

Bleeding from the tracheostomy can be a minor or life-threatening complication and occurs after tracheostomy about 5% of the time.4 Minor bleeding is typically noted in the first 48 hours after placement and may be addressed with local wound care, dressings (including TXA-soaked gauze), and silver nitrate cauterization (4).

Though uncommon, perhaps the most feared tracheostomy emergency is the development of a tracheo-arterial fistula leading to massive hemorrhage. The most common artery involved is the innominate artery given its proximity anterior to and overlying the trachea (yellow star). The incidence of tracheo-innominate artery fistula is less than 1%, but mortality due to hemorrhage is nearly 85% (4,8). A tracheo--innominate fistula usually forms 3-4 weeks after tracheostomy in about 70% of patients, however it can develop at any time (9). Presentation includes a sentinel bleed in about half of cases, and therefore a high index of suspicion must be maintained when tracheostomy bleeding occurs in the first few weeks of placement. A pulsating tracheostomy tube is essentially pathognomonic for a tracheo-arterial fistula, although it is not always present (9). Risk factors to the development of a tracheo-innominate fistula include incorrect tracheostomy tube size and length, placing the tracheostomy too low, overinflation of the cuff, and anatomical variation in location of the innominate artery (9).

In the case of hemorrhage secondary to tracheo-arterial fistula, definitive management includes median sternotomy, ligation of the artery, and repair of the fistula. Emergency department management includes the following (8):

Overinflate cuff in an attempt to tamponade bleeding (normal cuff pressure ~20cm H2O)

Place external pressure on the innominate artery via posterior sternal notch pressure

If uncuffed tracheostomy tube, pass endotracheal tube, inflate the cuff, and remove tracheostomy tube

If unsuccessful, remove tracheostomy tube and place finger directly into stoma then pull anteriorly to manually occlude the artery (termed the Little Dutch Boy maneuver) (7)

If oxygenation and ventilation required, can bag-valve-mask ventilate from above

Emergent surgical management

While this is a highly morbid complication that requires definitive operative management, direct pressure via finger tamponade of the artery effectively manages the hemorrhage prior to surgery in 90% of cases (8).

Additional Resources

In case you are more of a visual learner, here are some great additional resources including additional information on components of a trach and common emergencies, an algorithm for emergency laryngectomy patients, and an algorithm for emergency tracheostomy patients.

References

McGrath BA, Bates L, Atkinson D, Moore JA. Multidisciplinary guidelines for the management of tracheostomy and laryngectomy airway emergencies. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(9):1025-1041. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2012.07217.x

Hyzy R, De Cardenas JL. Tracheostomy in adults: Techniques and intraoperative complications. In: Feller-Kopman D, Finlay G, eds. UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer; 2023. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/tracheostomy-in-adults-techniques-and-intraoperative-complications?source=mostViewed_widget#H3800086655

Mehta S, Cook D, Devlin JW, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of delirium in mechanically ventilated adults. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(3):557-566. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000000727

Fernandez-Bussy S, Mahajan B, Folch E, Caviedes I, Guerrero J, Majid A. Tracheostomy Tube Placement: Early and Late Complications. Journal of Bronchology & Interventional Pulmonology. 2015;22(4):357-364. doi:10.1097/LBR.0000000000000177

Spataro E, Durakovic N, Kallogjeri D, Nussenbaum B. Complications and 30-day hospital readmission rates of patients undergoing tracheostomy: A prospective analysis. The Laryngoscope. 2017;127(12):2746-2753. doi:10.1002/lary.26668

Das P, Zhu H, Shah RK, Roberson DW, Berry J, Skinner ML. Tracheotomy‐related catastrophic events: Results of a national survey. The Laryngoscope. 2012;122(1):30-37. doi:10.1002/lary.22453

Hyzy R, McSparron J. Tracheostomy: Postoperative care, maintenance, and complications in adults. In: Feller-Kopman D, Finlay G, eds. UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer; 2024. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/tracheostomy-postoperative-care-maintenance-and-complications-in-adults?search=tracheostomy%20complications&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1%7E150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

Kapural L, Sprung J, Gluncic I, et al. Tracheo-Innominate Artery Fistula After Tracheostomy. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 1999;88(4):777. doi:10.1213/00000539-199904000-00018

Bradley PJ. Bleeding around a tracheostomy wound: what to consider and what to do? The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 2009;123(9):952-956. doi:10.1017/S002221510900526X

Authorship

POST BY Kate Gallen, MD

Dr. Gallen is a PGY-1 in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati.

EDITING BY ANITA GOEL, MD

Dr Goel is Assistant Professor in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati and an assistant editor of TamingtheSRU.com

Cite As: Gallen, K., Goel, A. Diagnostics and Therapeutics: Tricks of the Trach. TamingtheSRU. www.tamingthesru.com/blog/diagnostics/trachtricks. ***date***