A Test of Limitations - Urine Drug Screens

/The urine drug screen (UDS) is a relatively inexpensive and quick test to obtain in the emergency department, but how useful is it?. You may be tempted to order it for a patient who comes in altered or intoxicated. Before ordering, it is important to understand how the UDS works and its limitations.

How does it work?

Laboratory drug testing can be completed with a variety of biological samples, including blood, saliva, hair, nails, and urine. Urine is typically used in the emergency department. The most common type of UDS utilizes immunoassays which use the interaction between antibodies and drugs or drug metabolites to detect for the presence of substances. Advantages of UDS immunoassays include relatively low cost and rapid detection. Additionally, this type of testing can be easily automated and functions well in terms of work-flow in a lab. However, there are disadvantages including false-positives and need for confirmatory testing for positive results. The gold standard for laboratory drug testing is gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Why not just use GC-MS every time? GC-MS is more time consuming, costs more, and requires additional expertise for interpretation limiting its use in the ED.

Important to note that there can be variation between the substances tested on a UDS between different institutions and manufacturers.

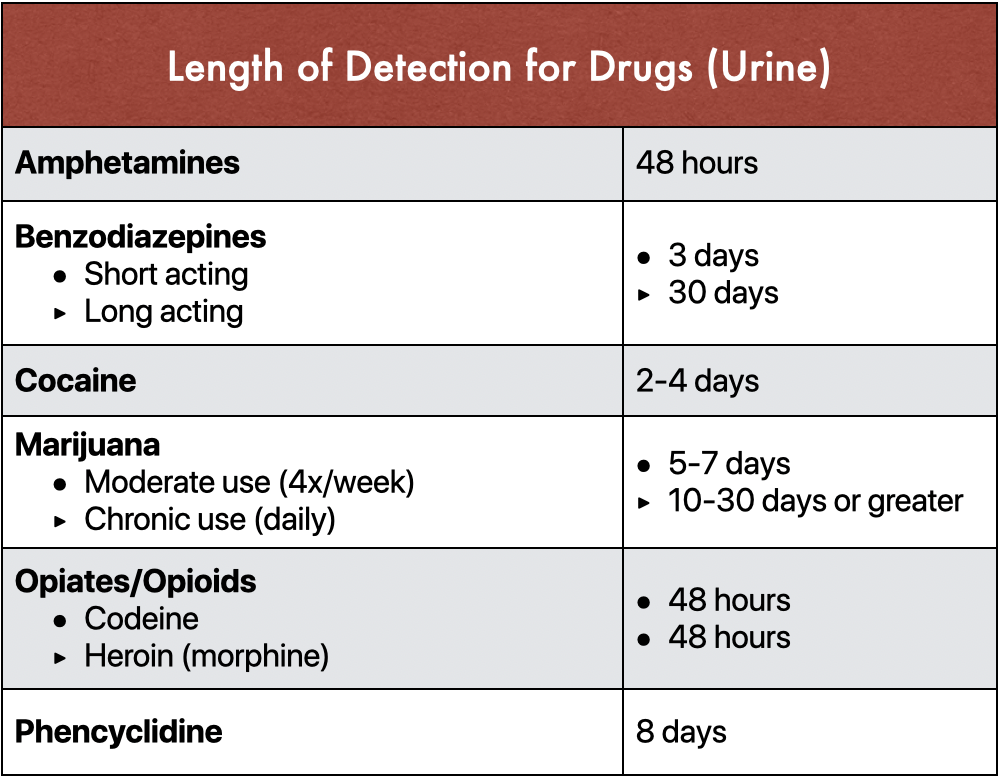

Detection times

Adapted from Moeller KE, Kissack JC, et al. Clinical Interpretation of Urine Drug Tests: What Clinicians Need to Know About Urine Drug Screens. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92(5):774-796.

The length of time a substance is detectable in the urine depends on several factors. Factors that are dependent on the substance or drug itself include metabolites, half-life, drug interactions, occasional versus chronic use, and last ingestion time. Patient factors can also dictate detection time, including body mass, urine concentration, and pH of urine. Additionally, there has been variability in detection windows seen from test to test.

Limitations and Pitfalls

There are several important considerations clinicians must use when ordering a UDS. First, that UDS provides a qualitative result. The results are either positive or negative. No information is provided on “levels” of certain substances. Additionally, information regarding which specific drug has been taken isn’t available. For example, the result may be positive for benzodiazepines but will not tell the clinician which drug in the class is present.

There are thresholds established for different substances. In order for a test to be positive, values must exceed a numeric cutoff, which differ from drug to drug. This was created in an attempt to decrease false-positive results. For example, poppy seed consumption can cause false-positive opioid results on UDS so the threshold for detection was increased in an attempt to eliminate this phenomenon. This can also cause a potential for false-negative results if a drug is present but the level does not exceed the lab cutoff level.

Positive results must also be taken with caution, as many over-the-counter medications and therapeutic medications can cause positive results for different drugs. All positive results are therefore considered “presumptively positive” and should undergo confirmatory testing.

Amphetamines

Amphetamines are often prescribed for therapeutic purposes, such as patients with attention deficit disorder, but can also serve as substances of misuse due to stimulant and euphoric effects. The UDS for amphetamines is thought to have good sensitivity for amphetamine salts. A positive result can be difficult to interpret as there are many medications that can cause false-positives due to cross-reactivity and similar chemical structures. These medications include over-the-counter decongestants and cold medications (pseudoephedrine, ephedrine, phenylephrine), psychiatric medications (bupropion, promethazine, trazodone, and TCAs), and labetalol. There are also some compounds that can result in false-negatives, including MDMA and “bath salts.”

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines can be used for their anxiolytic, antiepileptic, and sedative properties. There is also potential for abuse.

The most common metabolites that are detected by UDS are oxazepam and nordiazepam. Some benzodiazepines, such as diazepam and chlordiazepoxide, are metabolized to oxazepam. However, other commonly used substances, like alprazolam and clonazepam, can be missed as their metabolites are not detected. This can result in false-negative results. There have also been reports of false-positive results with patients using sertraline and oxaprozin (NSAID).

Cannabinoids

The most commonly used “illicit” substance in the US is marijuana. The main component responsible for the effects of marijuana is delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). The UDS tests for THC’s main metabolite, 11-nor-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol-9-carboxylic acid.

Several medications have been found to cause false-positives for the cannabinoid screen including proton pump inhibitors, NSAIDs, and antiretroviral therapies. Some hemp-containing foods have also caused positive results. There has been an increase in synthetic marijuana use and these substances are not picked up by the UDS.

A positive result for cannabinoids can be difficult to differentiate between acute and chronic use. THC has lipid solubility that can cause it to be stored in the body for weeks. Some studies have shown that single use of marijuana can be positive in the urine for up to a week after use. Long-term users can continue to have positive results after cessation, with some studies demonstrating positive results 46 days after last use.

Cocaine

The UDS immunoassay assesses the presence of cocaine’s main metabolite, benzoylecgonine. There are not many substances that cause false-positives, although there have been some reports that products from coca plant leaves, such as coca leaf tea, can result in positive results. Overall, the UDS for cocaine is thought to be a sensitive and specific test.

Opioids

Opiates are naturally occurring from the opium poppy seed and the metabolite, morphine, is tested for by the UDS immunoassay.. Rifampin, dextromethorphan, and quinolones have caused false-positives.

Opioids are synthetic derivatives with similar effects to opiates. These include hydrocodone, oxycodone, fentanyl, and methadone. Fentanyl and oxycodone are not typically detected under the opioid drug class and must be tested for separately. Some UDSs do incorporate additional testing of these two. Methadone is often used for opioid dependence and chronic pain but needs additional testing to confirm its presence as well as routine UDS panels that do not test for it. There have been false-positives for methadone seen with verapamil, diphenhydramine, doxylamine, and quetiapine.

To detect heroin and distinguish it from other substances in this class, its metabolite, 6-monoacetylmorphine (6-MAM), can be tested for separately.

Phencyclidine (PCP)

PCP is a dissociative anesthetic that has declined overall in popularity for street use but occasional spikes in use are still seen. Many substances are frequently laced with PCP, mainly marijuana.

Substances resulting in false-positives for PCP include dextromethorphan, diphenhydramine, ketamine, and tramadol. These are thought to be structural analogs or similar to PCP. However, cases of false-positives have also been seen with venlafaxine and lamotrigine, which are structurally distinct.

Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCA)

Tricyclic antidepressants aren’t typically thought of as drugs of abuse. However, some institutions have UDS tests with ability to test for TCAs. TCAs have a narrow therapeutic index. Intentional or unintentional overdoses of TCAs can be fatal. Several structurally similar medications to TCAs have resulted in positive results due to cross-reactivity; these include carbamazepine, cyclobenzaprine, and quetiapine. There can also be false-negatives if a test does not measure both parent compound as well as metabolite for select TCAs.

Adapted from Moeller KE, Kissack JC, et al. Clinical Interpretation of Urine Drug Tests: What Clinicians Need to Know About Urine Drug Screens. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92(5):774-796.

When is a UDS clinically useful?

Great question. Many studies have looked into the utility of a UDS in the emergency department and concluded that management of a patient often does not change after getting a UDS. This also seems to be the case in pediatric patients, even if a comprehensive drug screen is used. Studies found increased length of stay and cost when UDS is ordered in the ED for psychiatric patients, but it rarely changed management.

References

Algren DA, Christian MR. Buyer Beware: Pitfalls in Toxicology Laboratory Testing. Mo Med. 2015 May-Jun; 112(3): 206-210.

Brahm NC, Yeager LL, et al. Commonly prescribed medications and potential false-positive urine drug screens. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2010;67:1344-1350

Christian MR, Lowry JA, Algren DA, et al. Do rapid comprehensive urine drug screens change clinical management in children? Clin Tox. 2017;55:977-980

Hill, J. The Urine Drug Screen- Know Thy Limitations. Taming the SRU. http://www.tamingthesru.com/blog/intern-diagnostics/uds-know-thy-limitations

Moeller KE, Kissack JC, et al. Clinical Interpretation of Urine Drug Tests: What Clinicians Need to Know About Urine Drug Screens. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92(5):774-796.

Moeller KE, Lee KC, Kissack JC. Urine Drug Screening: Practical Guide for Clinicians. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2008 Jan; 83(1):66-76.

Riccoboni ST, Darracq MA. Does the U Stand For Useless? Urine Drug Screen and Emergency Department Psychiatric Patients. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2016 Oct. 68:84-85.

Saitman A, Park HD, Fitzgerald RL. False-Positive Interferences of Common Urine Drug Screen Immunoassays: A review. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 2014;38:387-396.

Tenenbein M. Do you really need that emergency drug screen? Clinical Toxicology. 2009; 47:286-291.

Thomas S, Knezevic C. Urine drug screens: Caveats for interpreting results. Contemporary Pediatrics. https://www.contemporarypediatrics.com/pediatrics/urine-drug-screens-caveats-interpreting-results. Published June 18, 2019. Accessed April 20, 2020.

Tox & Hound. Tox and Hound – U(ds) and I. EMCrit Blog. Published on May 13, 2019. Accessed on April 30th 2020. Available at [https://emcrit.org/toxhound/uds-and-i/ ].

Wu AH, McKay C, et al. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory Medicine Practice Guidelines: Recommendations for the Use of Laboratory Tests to Support Poisoned Patients Who Present to the Emergency Department. Clinical Chemistry. 2003;49(3):357-379.

Authorship

Written by Simi Mullen, MD PGY-1, University of Cincinnati Department of Emergency Medicine

Editing and Posting - Jeffery Hill, MD MEd