Grand Rounds Recap 11.8.17

/oral boards with DRS. STETTLER and ROCHE

Case 1: The patient is a middle-aged male with a history of hypertension who reports that after a night of drinking, he woke up with chest pain, shortness of breath and palpitations. Vitals are notable for a HR of 170 bpm and a BP of 70/30. He is in mild respiratory distress with an oxygen saturation of 88% on RA with respiratory rate of 40 breaths/min. Exam is otherwise non-revealing. A 12 lead EKG reveals a fib with RVR.

As the patient was hemodynamically unstable, the providers elected to start with electrical cardioversion after an appropriate pre-sedation assessment, consent and airway setup. He receives 0.15 mg/kg of etomidate and undergoes synchronized cardioversion at 100 J. After cardioversion, his HR is 95 bpm and blood pressure improves to 110/70. He is now satting 94% on RA. Labs are grossly unremarkable. Post-cardioversion EKG reveals a sinus rhythm without ischemia.

In this case, the critical actions were to obtain a rapid EKG and a troponin, to prepare airway equipment with appropriate pre-sedation assessment, perform synchronized cardioversion with appropriate and safe sedation, and admit the patient to a telemetry bed. Discussion of this case centered around the role of anticoagulation after a possibly provoked episode of atrial fibrillation (i.e., "holiday heart"). With a low CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1, the decision was made not to anticoagulate the patient and admit to the hospital for observation on telemetry.

Case 2 (A Multi-Case Encounter):

Case 2.1 is a 36 year old G2P2 who is six days post-partum. She is complaining of shortness of breath as well as central chest pressure. This has been present since the delivery, but has been worse over the last few days. Her BP is 160/100 with a HR in the 90s and she is saturating 94% on RA. On exam, she is noted to have bilateral lower extremity edema, and appears uncomfortable with her work of breathing. A CXR is notable for significant pulmonary edema. The patient is placed on BiPAP with some improvement of her dyspnea, although she continues to get progressively hypertensive as the encounter progresses. She is given push-dose labetalol with some improvement of her blood pressure. She is then placed on a nitro drip with gradual improvement of her hemodynamics. She is also given magnesium.

Due to concern for post-partum cardiomyopathy vs pre-eclampsia, OB is consulted, as well as cardiology for flash pulmonary edema. She is given lasix for diuresis and admitted to the cardiac ICU in slightly improved condition.

Case 2.2 is a young male complaining of arm pain. He is a 34 year-old-male with no significant PMH who presents with a self-reported spider bite to the left forearm. He reports a history of a similar "spider bite" in the other arm in the past. He is reporting severe pain in the affected forearm. He has a BP of 90/50, a HR of 120 and a temperature of 101F. On exam, he has a boggy, erythematous and exquisitely tender area of swelling involving the distal left forearm. He has significant pain with any ROM of the forearm or hand. He is noted to have rapidly progressing redness while the case progresses.

He is given IVF as well as oral and IV pain control. An XR of the forearm reveals subcutaneous gas, concerning for necrotizing fasciitis. Labs are notable for a WBC of 18, an elevated lactate and hyponatremia. Hand surgery is consulted. He is started on broad-spectrum antibiotics to cover gram-positive, gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria, and is rapidly taken to the OR for definitive management.

Case 2.3 is an elderly woman who got assaulted by a neighbor. She has a history of atrial fibrillation and is on Eliquis. She was hit in the face with a heavy object and is complaining of both head and dental pain. She denies loss of consciousness and has a GCS of 15. Her neurologic exam is intact. Focused physical exam reveals a fractured lateral incisor with some bleeding from the pulp with an otherwise normal HEENT exam. Given her age, reported head trauma and anticoagulation, a head CT is ordered, which is unremarkable. Her exposed dentin is covered with Dycal, and she is given emergent dental follow up.

Faculty Simulation with DRS. fernandez, hill and stolz

You are at a community hospital in the middle of the night. The first patient is a young female who presents with abdominal pain. She reports a few days of worsening, sharp lower abdominal pain. She is borderline tachycardic with a blood pressure of 101/59. She appears uncomfortable on exam and is diffusely tender in the lower abdomen. She denies fever and reports her last menstrual cycle was 5 weeks ago. She also denies dysuria, diarrhea, or vomiting.

A urine pregnancy test is positive. A bedside point-of-care ultrasound is concerning for free fluid in the pelvis. A FAST is positive in the RUQ. She becomes progressively hypotensive and tachycardic while awaiting definitive management. OB is contacted, and they prepare to take the patient to the OR. Blood is ordered from your community hospital's blood bank, but the patient goes to the OR before receiving any product.

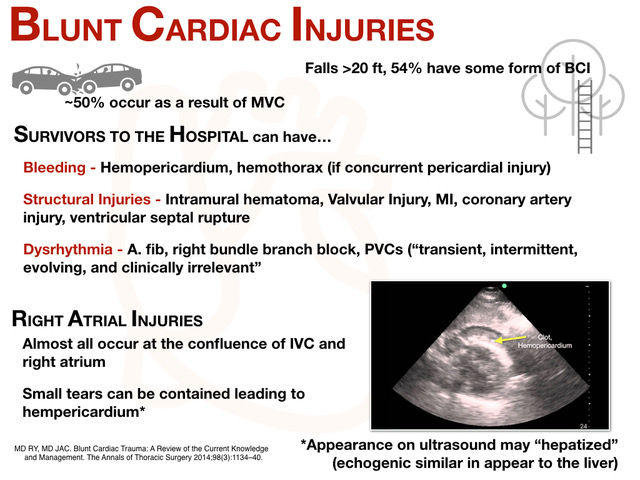

During the management of the first patient, a second patient arrives via EMS who was involved in a MVC. He is complaining of significant chest pain as well as hip pain. His primary survey is notable for an intact airway and clear breath sounds bilaterally with intact pulses. He is tachycardic to 125 with a blood pressure of 88/71. He is saturating 95% on RA. He is noted to have significant ectopy on EKG concerning for blunt cardiac injury. Physical exam is notable for significant ecchymosis to the chest and upper abdomen. Due to his hypotension and complaints of pelvic pain, a TPod is applied. An eFAST is positive in the pericardium. A pelvic XR is notable for a widened pubic symphysis; a CXR is notable for a slightly enlarged cardiac silhouette and evidence of pulmonary contusions. Blood is ordered from the blood bank; however, there is a delay in getting the blood.

Given this, trauma services at the local trauma center are contacted. The patient is prepped to transfer the patient via helicopter EMS to the trauma center. However, while awaiting transport, the patient becomes progressively hypotensive and altered, so an emergent pericardiocentesis was performed with some improvement of his hemodynamics.

R1 Clinical Knowledge - Neonatal Rashes with Dr. Gleimer

In general, most neonatal rashes are benign and can be managed expectantly. Neonatal skin is thinner, less hairy, more fragile and less structurally developed than adult skin, and rashes are more common presentations in this age group. Below, we discuss some of the highlights of common neonatal rashes and their basic management.

Erythema Toxicum Neonatorum

- Erythematous rash with pustules that spares the palms and soles.

- 40-70% prevalence, more common in full term infants

- Usually appears at 24-48 hours of life

- Baby looks otherwise well, afebrile and happy

- Etiology unclear; eosinophilic infiltrate seen on biopsy

- Management involves reassurance and close follow up with pediatrician

Neonatal Cephalic Pustulosis ("Neonatal Acne")

- Most commonly papules and pustules on the face

- Common with an up to 20% prevalence

- Seen at age 2-3 weeks of life, resolves after 1 year

- May be related to Pityrosporum Malassezia

- Management involves reassurance and expectant management; ketoconazole cream may help as well

Transient Neonatal Pustular Melanosis

- Seen in up to 5% of newborns of color

- Involves vesicles and pigmented macules; may be surrounded by scale

- Usually spares palms and soles

- Management involves reassurance; rash fades in a week and dark spots fade in six months

Miliaria ("Heat Rash")

- Common and seen in up to 15% of newborns

- Caused by fever or hyperthermia

- Due to inappropriate closure of eccrine ducts

- Management involves expectant management, removal from heat

Seborrheic Dermatitis ("Cradle Cap")

- Seen from 3 weeks to 2 years of age

- 7-10% prevalence

- Presents with salmon-colored greasy, scaly patches to the scalp

- Management involves ketoconazole cream and steroid cream with follow up

Cutis Marmorata

- Seen in up to 50% of infants

- Lacy reticular rash associated with cold exposure

- Is a vascular response to cold

- Management involves warming the infant and expectant management

Harlequin color change

- Seen in up to 10% of healthy newborns

- Presents at day 2-5 of life

- Transient erythema of 1/2 of the infant and is gravity-dependent

- Thought to be secondary to hypothalamic immaturity

- Management involves expectant management

Herpes Simplex

- Vesicular lesions on an erythematous base in clusters

- Usually acquired peri/post-natally

- Can involve the skin, mouth or eyes

- Can progress to CNS and multi-organ involvement

- Can have devastating sequelae if missed early; untreated disease carries 80% mortality

- Management includes admission, antivirals and resuscitation as needed

Petechial Rashes

- Newborn with petechial rash (always concerning), secondary to thrombocytopenia

- Differential of petechial rashes includes ITP, DIC, RhD alloimmunization

- Management includes admission and full work up

R4 Case follow up- Cardiac tamponade with Dr. Renne

58 y/o male with a history of CAD, HTN, DM, ESRD on HD, atrial fibrillation on warfarin with a recent ablation two weeks ago who presents with LLQ abdominal pain. He reports some shortness of breath, vomiting and abdominal pain for the last three days. Upon presentation, he is hemodynamically stable but does have a tender LLQ on exam. A CXR is unchanged from one done post ablation, but does mention an enlarged cardiac silhouette. Given his recent ablation, a bedside cardiac ultrasound was performed, which revealed a large pericardial effusion. The patient was moved to the SRU. An a-line was placed, which revealed pulsus paradoxus. He was also found to be hyperkalemic and was given insulin, d50 and calcium. The cardiology fellow came to the bedside, and a bedside echo revealed tamponade physiology. His INR then returned at 14.8, and he subsequently received both Vitamin K and PCCs.

He was taken emergently to the cath lab, where a pericardial drain was placed. He continued to improve in the hospital with normalization of his INR; his drain was removed on hospital day 5 and he ultimately did well.

Who should get a cardiac ultrasound in the ED? This patient presented with LLQ pain; he was scanned due to his recent ablation and anticoagulated status. Don't discount risk factors, but also include clinical gestalt: something about this patient didn't sit right with the providers, so they did more. Some common symptoms of patients who were ultimately diagnosed with cardiac tamponade include dyspnea, chest pain, near syncope, cough, hoarseness, unexplained anxiety or even hiccups!

Patients with pericardial effusions and/or tamponade will present with tachycardia (77%), tachypnea (80%), JVD (76%), pulsus paradoxus (82%). Only 40% of patients will have the classic Beck's Triad, and only 26% of patients will present with hypotension. The classic EKG finding of low voltage is only present in 46% of patients, although cardiomegaly is seen on CXR 89% of the time. The combination of cardiomegaly, tachypenia and tachycardia strongly suggests a possible pericardial effusion -- especially in the patient with the right risk factors. Bedside ultrasound is easy, quick and non-invasive -- so use it to help narrow down your diagnosis in these patients.

How do you diagnose a tamponade?

- By hemodynamics: decreased pulse pressure, decreased MAP

- By echo: RA and RV collapse

- By volumetrics: usually 300 mL or greater in the pericardial sac

What is the ED management? In general, our role is temporizing these patients until they can receive definitive management. For patients who are hypotensive, you can start with a gentle fluid bolus of around 500 mL to increase preload. However, too much fluid can challenge the RV and can make coagulopathy worse. If fluids don't improve hemodynamics, move quickly to vasopressor support, and consider primarily going to your inotropes: epinephrine, dobutamine or even calcium. For patients with profound coagulopathy, like this patient, reversal should start in the ED and should be targeted at the specific agent. In addition, make sure to address other life threats that may accompany these patients, such as hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis or other areas of spontaneous hemorrhage in the profoundly coagulopathic patient. Avoid endotracheal intubation unless you are forced to act based on the patient's respiratory status -- the change in intrathroacic pressure and effects on preload can be disastrous in these patients. And finally, be prepared to act: have your pericardiocentesis kit ready if the patient becomes more unstable prior to definitive management with a pericardial drain.

pediatric emergency medicine - pediatric syncope with dr. Fananapazir, PEM Fellow

- Syncope represents 1-3 % of all pediatric ED visits

- More common in adolescents, more common in females

- Can be thought of as cardiogenic ( < 1% of all pediatric syncope) versus non-cardiac in etiology

Cardiogenic Etiologies of Syncope in Pediatric Patients

- Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HOCM)

- Long QTc: can be congenital, such as Roman-Ward syndrome, or acquired, due to medication side-effects or electrolyte disturbances

- Congenital Short QTc Syndrome

- Preexcitation Syndrome: such as WPW; found in 3% of pediatric patients with sudden death

- Brugada Syndrome: rare in pediatric patients but still possible

- Catecholaminergic polymorphic VT/VF

- Heart block

- Commotio Cordis

- Myo/pericarditis

These patients often present with an abnormal EKG, chest pain, a concerning family history, persistent tachycardia or a classic history.

Non-cardiogenic Etiologies of Syncope in Pediatric Patients

- Vasovagal Syncope

- Pregnancy

- Metabolic derangements

- Ingestion

- Seizure

- Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS): common in teenage girls; up to 40% patients with POTS will have syncope

- Eating disorders

- Exercise-associated: post-exercise, due to loss in skeletal muscle tone and abrupt decrease in venous return

- Anaphylaxis

Breath-Holding Spells

- Can mimic syncope

- Usually seen in children from age 6 months to 24 months, although can be seen as patterned behavior up to age 8

- Triggered by an emotional insult such as pain, anger or fear

- Can be cyanotic, which leads to apena and possible syncope, or "pallid," which can be induced by vagal tone and bradycardia

- May be associated with brief posturing or tonic-clonic motor activity that mimics seizures

- Thought to be secondary to autonomic dysfunction or hypersensitivity

- Some evidence that in anemic patients, iron supplementation can improve the frequency of these spells, so consider checking a CBC

Other Syncope Mimics

- Seizures: ask about aura or a postictal phase

- Migraine syndromes: particularly basilar migraines; ask about aura, headache, nausea, vertigo

- Intracranial mass: usually present with clear, abnormal neurologic examination

- Psychogenic

- Hyperventilation: ask about paresthesias or preceding anxiety

- Intentional strangulation activities (e.g., "the choking game")

- Narcolepsy and cataplexy: ask about chronic sleepiness, hypnogogic hallucinations, sleep paralysis

Workup

- What are the "green flags" for pediatric syncope that make you less concerned? If it is postural, associated with dehydration, associated with stress or anxiety, fits one of the classic postural syndromes, or if the patient is back to baseline and feels well.

- What are the "red flags?" Young age (less than <10), multiple episodes in a short period of time, associated with chest pain or they have ongoing chest pain, occurs during exercise, occurs while recumbent or sitting, strong or concerning family history, or if the patient has a complex past medical history.

- For patients who have returned to baseline and have an otherwise unconcerning story, there is poor evidence for checking electrolytes, a CXR or a head CT (which is performed in up to 58% of pediatric syncope).

- Tilt table testing can be used on an outpatient basis for patients with recurrent postural syncope.

- Orthostatic vital signs are neither sensitive nor specific for the etiology of syncope in pediatric patients; in one study, up to 44% of healthy adolescent volunteers were found to be orthostatic

- EEG is only used when there is a concerning story for seizure, and usually as an outpatient unless the patient is not back to their neurologic baseline.

- Cardiac enzymes are ordered on up to 15% of pediatric syncope patients in the community; this is only useful if there is a concerning EKG.

- Urine pregnancy test should be ordered for all menarcheal females; consider CBC if history of heavy periods, coagulation disorders or there are concerning physical exam findings such as conjunctival pallor.

- Consider a fingerstick glucose in the appropriate patient populations, those with neurologic symptoms or if the history suggests hyper- or hypoglycemia.

Indications for Admission

- Evidence of cardiovascular disease or compromise

- Persistent neurologic deficits

- Has consistent symptomatic orthostasis despite adequate resuscitation in the ED

- Significant injury from syncopal event

Discharge and Follow-up

- Most patients can go home with PCP follow up

- CCHMC does have a Syncope Clinic (cardiology and neurology) with whom patients can follow up as well

- May get a Holter Monitor if their episodes are frequent

- Recommend that patients increase fluid intake (30-50 cc/kg each day) and avoid caffeine or other precipitants