Dental Infections: To Treat or Not to Treat?

/Remember as a kid when you would come downstairs only to find your parent devouring your hard-earned Halloween candy? Consider it a favor. Though delicious, those globs of sticky sugar are a common culprit of toothaches for kids & adults alike, as well as headaches for emergency room providers. Whether in the emergency department itself, or while being cornered by a neighbor as you head out your front door, we are commonly confronted by someone holding the side of their face in agony, slowly mumbling ‘can you help me doc?’, as they wince in pain in between each word. Though our medical curriculum may not have prepared us for these moments, medicine is all about lifelong learning, so it is up to us to fill the knowledge gaps about those 32 pearly whites that are often the cause of much trouble.

Epidemiology and Basic Tooth Anatomy

A study conducted by Lewis et al, tracking ED visits nationally throughout the US over a 4-year period, found that dental complaints account for 0.7% of all ED visits. (1) To put that into perspective, that is as common of a chief complaint as “painful urination” in the ED. Since we know a few things about the kidneys and bladder, it is only appropriate that we get just as comfortable with our knowledge about teeth.

Thankfully, unlike the complex anatomy of renal nephrons, the anatomy of teeth is much simpler and can be summed up using the bullet points below. A tooth consists of three basic layers. Starting on the outside, enamel surrounds the exposed crown portion of a tooth, is considered the hardest substance in the human body and is composed mainly of hydroxyapatite. Moving further inwards, dentin is living tissue and consists of a microtubule network filled with odontoblastic processes and extracellular fluid. Lastly and certainly not least, the most inner portion of a tooth is pulp, which, like dentin, is living tissue and holds the neurovascular supply of the tooth. While enamel is localized to the crown of a tooth, dentin and pulp extend from the crown all the way down to the root of the tooth. The root is externally covered by cementum and attaches to the surrounding alveolar bone via periodontal ligament. Having a basic layout of tooth anatomy in your mind allows you to localize the site of the dental complaint without ever going to dental school. This is because while the pulp contains pain-sensitive fibers, only the periodontal ligament contains pain- and pressure-sensitive fibers. Asking patients about sensitivity to sweets versus pain with chewing may help you localize the issue even before asking the patient to say “ahh!”. (2,3)

Crown- visible portion of tooth

Enamel (outermost, hard substance)

Dentin (living tissue below the enamel)

Pulp (innermost, living tissue, contains the neurovascular bundle)

Root- embedded in gingiva and attaches to the alveolar bone of jaw

Cementum (outermost, anchors root to alveolar bone via the periodontal ligament)

Dentin (below the cementum)

Pulp (neurovascular bundle exits via the apical foramen at the root apex)

Irreversible Pulpitis

A patient presents to the ED with a toothache and, after quickly brushing up on your dental anatomy, you confidently walk into the exam room. After a few keen questions, you quickly learn that the toothache comes on only when eating candy or drinking an ice-cold soda and lasts minutes to hours. You scramble in search of a tongue depressor, put on a clean pair of gloves, and ask the patient to open wide. Though you’re clearly not a dentist, you know a cavity when you see one.

So before you grab your next handful of candy corn, consider if it’s more of a painful trick, than a tasty treat. As plaque bacteria breaks down those sugary snacks, it leaves behind acidic metabolic byproducts, which reside in the small pits of your once pearly whites. Gradually, the tough enamel barrier standing between you and pain begins to degrade. Eventually the wall of defense is breached and the oral environment can now directly interact with the living dentin and pulp. As you gulp down that ice-cold soda, those particles, once bound for your GI tract, can now travel down through the decaying tooth to the microtubules of the dentin and begin to inflame the underlying pulp- leading to pulpitis. This inflammatory process leads to painful sensitivity to various stimuli- from hot to cold, as well as sweet to sour. (2) Initially the pain is noticeable, but only lasts for seconds. But as you continue to ignore the slowly enlarging cavity, the more noticeable pain begins to last minutes to hours as you consume your favorite foods.

Overall, although our mouths are rich in microorganisms, the irreversible inflammation of the pulp in the setting of a progress dental cavity is considered to be an inflammatory process to the oral environment, rather than an infectious one. Regardless, antibiotics continue to be prescribed for patients presenting with such symptoms, despite little evidence of their efficacy. (4) In 2000, Nagle et al. established a randomized, double-blinded placebo-controlled study to see if oral penicillin versus placebo helps improve pain over a 7-day period in patients presenting with symptoms of irreversible pulpitis. In this study, a total of 40 adult patients were randomly assigned to either receive penicillin VK (500mg QID) or a placebo control, and were asked to keep a daily diary for tracking their symptoms, as well as number of pain medications taken. After a 7-day period, there was no significant difference in pain ratings or need for pain-relief medications between the two groups. (4)

Evidence such as the study listed above shaped the 2019 recommendations from the American Dental Association, who strongly recommended against prescribing antibiotics for otherwise healthy adults presenting with signs of irreversible pulpitis. (5) So as you head back from the exam room of the patient complaining of tooth pain only with cold, sweet drinks, ask yourself if you really need to place an order for an outpatient antibiotic.

Periradicular Periodontitis

Due to a nearly universal fear of dentists, we tend to ignore the ever worsening tooth sensitivity while eating, in hopes that it will miraculously self-heal. Unfortunately, this leads to extension of pulp disease into the root and apex of the tooth. Inflammation turns to necrosis, wreaking havoc on the tissues surrounding the tooth, including the periodontal ligament. Unlike the pulp, the periodontal ligament also carries pressure-sensing nerve fibers. (3) This fact isn’t only impressive at cocktail parties, but it also helps you better diagnose that patient with a toothache who is still eager to see you after spending hours in the ED waiting room. With a few simple percussive taps on the affected tooth, your patient cringes, and you astutely discern that there is now extensive inflammation and/or necrosis of the tissues surrounding the tooth. Now this surely has to require antibiotics, right?!

Using a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study, Henry et al. set out to investigate if administration of penicillin versus a placebo improves postoperative pain or swelling in adult patients with symptomatic necrotic teeth. A total of 41 adults with emergency presentation consistent with periradicular periodontitis were randomly assigned to receive penicillin (pen VK 500mg QID) or placebo (lactose), after undergoing appropriate endodontic treatment. Each patient kept a daily diary, which tracked generalized tooth pain, pain with percussion, and swelling. At the end of seven days, there was no significant difference found between the two groups in any of the categories. Furthermore, there was no difference in pain medication usage (ibuprofen and acetaminophen with codeine) between either of the groups as well. (6)

So, before rushing to look up the dose of otherwise rarely-used Pen VK, consider if the patient with a chronic dental cavity and ache that worsens with chewing actually needs it. Instead, consider a script for an NSAID or even a bedside nerve-block (as previously described on Taming the SRU), while resting assured that the ADA expert panel has your back. (5)

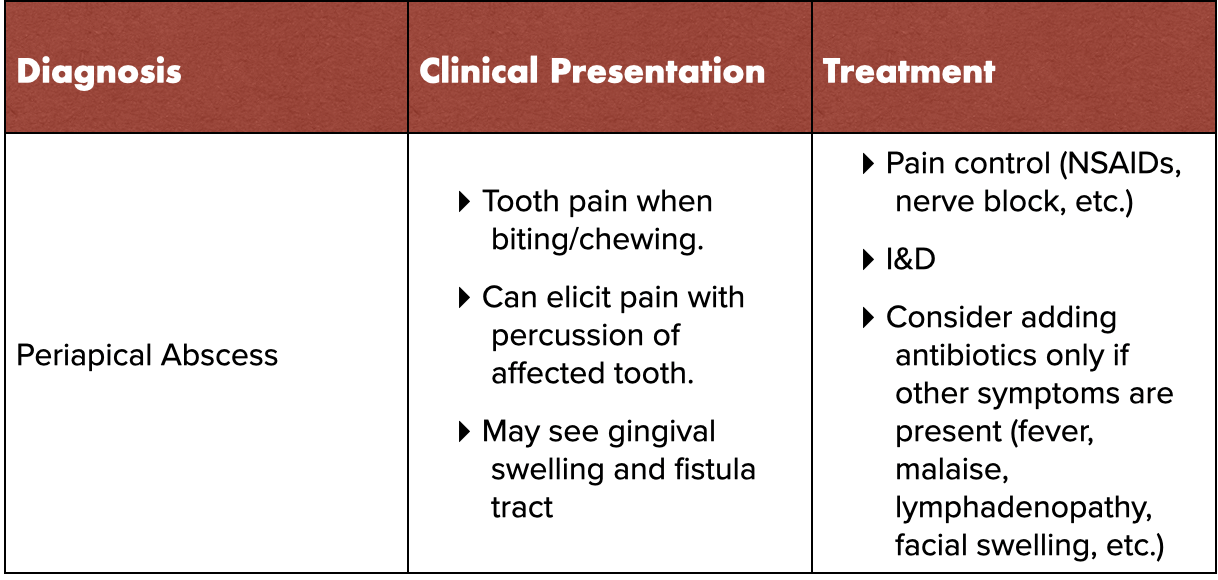

Periapical Abscesses

Unfortunately, dental disease is relentless and continues to progress if left unchecked. Once ignited by only a small cavity, the inflammation and necrosis of the tooth root and surrounding supporting structures can lead to the formation of a purulent pus pocket. (2) Though a periapical abscess often presents similarly to periradicular periodontitis, gingival swelling and a draining fistula tract above the affected tooth may steer you to the correct diagnosis. But before asking the patient if they have any allergies to any antibiotics and skipping out of the room in confidence, ask yourself if the pen is truly mightier than the scalpel.

In 1996, Fouad et al. utilized a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study to investigate if adding penicillin improves symptoms, compared to placebo, in adults presenting with periapical abscesses after undergoing local treatment. The study included 32 patients treated with an I&D and/or drainage through a root canal, prior to being randomly assigned to receive either penicillin (pen VK 500mg QID), a placebo, or neither medication. The patients monitored for the following 72 hours focusing on self-reported pain, swelling, and pain medication use. Ultimately, the authors noted “no clinically significant difference in the three groups as to the reduction or course of recovery”. (7)

As you go to grab your #11 scalpel, I know what you’re thinking: “surely a dentist can perform a procedure that will actually work better than something that I can quickly do in the ED at the bedside.” Kuriyama et al.reviewed records from 112 patients presenting to an emergency dental clinic with a periapical abscess. At the discretion of the provider, patient either received either an incision & drainage of the soft tissue swelling (n=105) or a surgical opening into the pulp chamber (n=7). Each was subsequently placed on an antibiotic and clinical signs & symptoms were monitored over the next 72 hours. Notably, 99% of the patients who underwent an I&D (104 of 105) were found to have statistically significant improvement in pain, extra-oral swelling, and temperature over that time period. Furthermore, patients undergoing an I&D had a higher overall improvement score after 72 hours, compared to patients undergoing a root canal opening (2.5 vs 1.4), though this wasn’t statistically significant given the limited number of patients who underwent a root opening procedure. (8)

Despite the data, >95% of providers self-reported prescribing a course of antibiotics to patients presenting with an acute periapical abscess. Furthermore, >40% still prescribed a course of antibiotics even after completing an I&D. (9) This is likely due to the fear that dental infections can spread into various facial spaces. For instance, dental infections are the primary cause of deep space neck infections- commonly presenting with neck/face swelling and fever. (2) So before you conclude that toothaches presenting in the ED don’t need to be prescribed antibiotics, think back to the principles of medical school and take a thorough H&P, specifically focusing on uncovering a potentially spreading, dangerous infection or identifying risk factors for more dangerous infections (like cigarette use, male sex, and alcohol use).

Finally, you get to a patient with a toothache that you’re certain needs an antibiotic. Aside from an obvious dental abscess, maybe that patient also has a fever or your exam reveals lymphadenopathy or very mild facial swelling. After you’ve assured yourself it’s not Ludwig’s angina or another deep space neck infection (see here if you need a refresher), you rush back to your computer, ready to write your first clinically-indicated antibiotic for dental pain. But which bug juice do you choose?

Intuitively, we know that our own mouths are filled with a rich array of microorganisms. In 2002, Khemaleelakul et al. set out to see if this intuition was correct, by aspirating a total of 17 periapical abscesses from patients presenting with symptoms concerning for spread. The study revealed that these abscesses are typically polymicrobial, as an average of 7.5 strains of bacteria were found per patient. The majority of the pathogens were anaerobes (63%), with Prevotella as the most prevalent species (53% of cases). The study went on to test the sensitivity of isolates to pen VK, amoxicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, clindamycin, and metronidazole, noting that >80% of isolates were sensitive to each of the antibiotics tested. Meanwhile, resistance was noted to be most prevalent to pen VK (>19% of isolates) and rarest for amoxicillin/clav (0% of isolates). (10)

Overall, amoxicillin should be considered your first choice in a patient with a dental infection that is concerning for spread. Since it has broader spectrum, is more readily absorbed in the GI tract, and is more readily available in plasma, it easily unseats the previously-beloved pen VK as the bug juice for teeth. (11) Nonetheless, medicine is part art and part science, so nothing is ever written in stone. So, when a patient presents to the ED with a tooth infection that is not responding to your antibiotic of choice, or maybe even has an antibiotic allergy, alternative regimens abound including: Amoxicillin/Clavulanic Acid, Clindamycin, Metronidazole, or Doxycycline. (12)

References

Lewis C, Lynch H, Johnston B. Dental complaints in emergency departments: A national perspective. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(1):93-99. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12827128/

Tintinalli JE, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Stapczynski J, Cline DM, Thomas SH. eds. Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 9e. McGraw-Hill; Accessed October 30, 2020.

Reichman EF. Emergency medicine procedures, second edition. McGraw-Hill Education; 2013. https://books.google.com/books?id=UZe-GXr5lxQC.

Nagle D, Reader A, Beck M, Weaver J. Effect of systemic penicillin on pain in untreated irreversible pulpitis. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 2000;90(5):636-640. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11077389/

Lockhart PB, Tampi MP, Abt E, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on antibiotic use for the urgent management of pulpal- and periapical-related dental pain and intraoral swelling: A report from the american dental association. J Am Dent Assoc. 2019;150(11):906-921.e12. https://jada.ada.org/article/S0002-8177(19)30617-8/fulltext

Henry M, Reader A, Beck M. Effect of penicillin on postoperative endodontic pain and swelling in symptomatic necrotic teeth. J Endod. 2001;27(2):117-123. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11491635/

Fouad AF, Rivera EM, Walton RE. Penicillin as a supplement in resolving the localized acute apical abscess. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 1996;81(5):590-595. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8734709/

Kuriyama T, Absi EG, Williams DW, Lewis MA. An outcome audit of the treatment of acute dentoalveolar infection: Impact of penicillin resistance. Br Dent J. 2005;198(12):759-63; discussion 754; quiz 778. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15980845/

Germack M, Sedgley CM, Sabbah W, Whitten B. Antibiotic use in 2016 by members of the american association of endodontists: Report of a national survey. J Endod. 2017;43(10):1615-1622. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28754406/

Khemaleelakul S, Baumgartner JC, Pruksakorn S. Identification of bacteria in acute endodontic infections and their antimicrobial susceptibility. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94(6):746-755. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12464902/

AAE position statement: AAE guidance on the use of systemic antibiotics in endodontics. J Endod. 2017;43(9):1409-1413. https://www.aae.org/specialty/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/06/aae_systemic-antibiotics.pdf

Daramola OO, Flanagan CE, Maisel RH, Odland RM. Diagnosis and treatment of deep neck space abscesses. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141(1):123-130. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19559971/

Authorship

Written by Max Kletsel, MD PGY-1 University of Cincinnati Dept of Emergency Medicine

Review, Editing, and Uploading by Jeffery Hill, MD MEd