Mastering Minor Care: Hand Lacerations

/Hand injuries are a common chief complaint in the ED with a considerable proportion being lacerations. Nearly 7 million hand lacerations were addressed in EDs across the country in 2018 following a reliable cyclic pattern that waxes in the summer months and wanes around December [1]. Regardless of the season, you can safely assume that you will encounter a hand laceration (or a few).

“Uncomplicated” hand lacerations are typically defined as: requiring closure with sutures, not due to a burn, human or animal bite, not associated with underlying fracture, tendon, nerve, arterial or large vessel injury, and not associated with severe surrounding soft tissue damage or maceration and will the the topic we cover in this post, covering both the repair and the critical H&P components to not miss potential complicated injuries.

can’t miss details in the history

Patients may come in with a straightforward HPI: “the knife slipped while I was trying to remove the avocado pit” or “the glass jar broke in my hand.” However, be sure to ask your patient and document certain elements of the history for every laceration you encounter:

The object: Glass and wood are common materials that can fragment into smaller pieces. Wood is not visible on Xray and would need to be removed by visual inspection and copious irrigation. Be aware that fragments may splinter during removal. Glass and metal are radiopaque and would justify an Xray to check for foreign bodies prior to closure (Image 1). Additionally, for metal, a point-of-care ultrasound can identify superficial metal foreign bodies. Inquiring about how contaminated the offending material was can inform your decision for possible antibiotic selection and whether to administer tetanus prophylaxis.

Tetanus: Is the patient vaccinated? When was their last booster shot? In general, patients should get a tetanus update once every 10 years. However, for patients presenting with lacerations, we give boosters in the ED for anyone who has not received a Tdap/Td booster vaccine within the past 5 years. If a patient is pregnant or has never received any form of tetanus toxoid vaccine before, immunization with Tdap is preferred. Certain demographics of patients are more likely to lack adequate seroprotection from tetanus toxoid, such as those over 70 years old, immigrants, and those with a history of inadequate immunization. Prophylaxis with human toxoid immunoglobulin is advised if a patient has received less than 3 previous doses of tetanus toxoid vaccination or has unknown vaccination status with a wound complicated by contaminants such as dirt, soil, or rust [16-17].

Mechanism: If the laceration was delivered with an associated crushing component, order an Xray to assess for underlying fracture. If present, this may indicate an open fracture and should consider involving your hand surgery consultant. Additionally, identify if the injury occurred while at work. Hand injuries are an overwhelming proportion of occupation related injury treated in the ED and will likely require paperwork to satisfy worker’s compensation [2, 3]. If a wound looks more severe than the reported mechanism or the story does not line up, keep a level of suspicion for abuse or self-inflicted harm. Chart review for any evidence of co-morbid psychiatric conditions and ask follow-up questions to assess the patient’s safety.

Timing: How long ago did the laceration occur? The longer a wound is open, the higher the risk of infection. This remains a difficult and ongoing area of study and there is no agreed upon time point at which you should choose to forego primary closure and allow healing by secondary intention. With emerging evidence, clean, non-infected wounds may be closed with sutures up to 18-24 hours after injury [4-6].

Can’t miss details in the Physical Exam

Evaluate the laceration in as much detail as possible: Where is it? Are there more than one or are there any other associated injuries? How deep does it go and is it gaping- can you see tendon, muscle, fat? Does it cross joint lines? Is it still actively bleeding? Is it linear or stellate or are the edges jagged? The image on the right (Image 2) has an example of how to describe a laceration.

Perform a neurovascular exam by checking gross motor function, sensory function and vascular status. It is paramount to ensure you don’t miss a deficit that escalates the laceration severity and may significantly impair your patient’s functioning if left unaddressed.

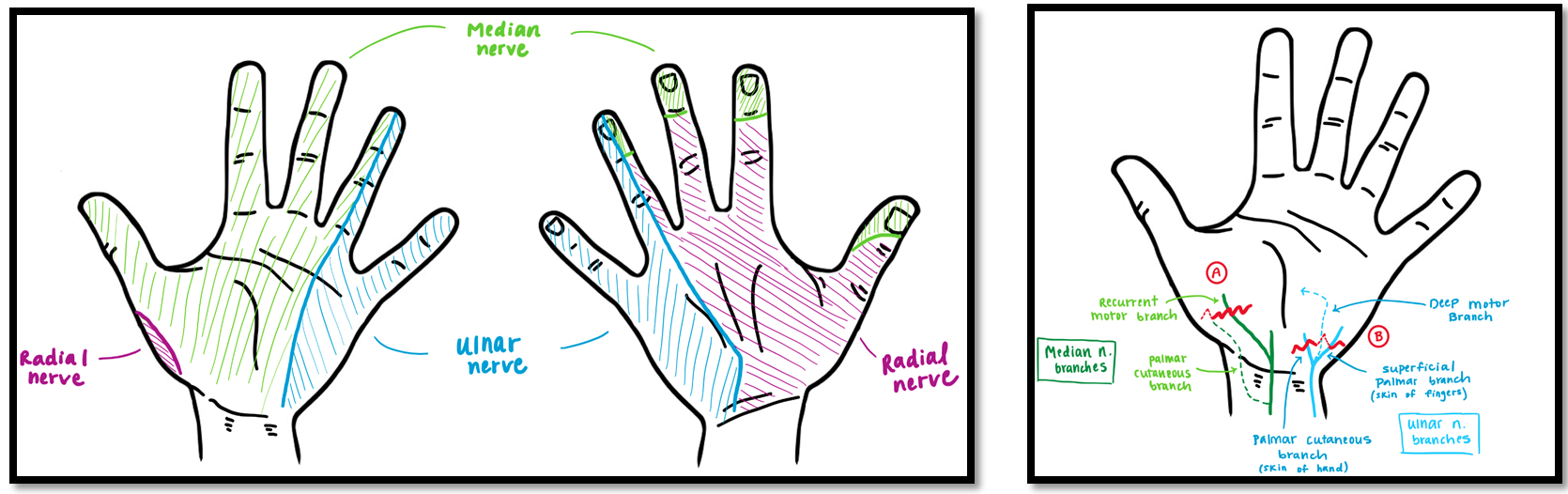

You can quickly evaluate for grossly intact motor function of the medial, radial, and ulnar nerves by asking the patient make an “OK sign”. Abnormalities in the appearance may suggest an underlying tendon or nerve injury. Additionally, have patients abduct and adduct their fingers, create a scissor motion of index and middle fingers and give a thumbs up sign to assess full range of motion of all digits. Perform a sensory exam by testing small regions of different dermatomal aspects of the hand to evaluate for deficits (Image 3, Left). A general tip for assessing both strength and sensation is to test both hands and compare your findings relative to the other. To assess vascular status, always check for capillary refill distal to the laceration.

In general, superficial palmar lacerations are more likely to cause isolated sensory deficits as the motor branches of the ulnar and median nerves course more deeply through the hand. An exception to this is the recurrent motor branch of the median nerve, which overlies the mid-thenar eminence superficially and is therefore easily severed presenting as inability to oppose the thumb with intact sensation over the thenar eminence (Image 3, Right).

Tips for Repair

Preparation for wound closure is just as important as the procedure itself. You may wear sterile or nonsterile gloves without affecting the risk of infection [8]. Thoroughly explore the entire depth of the wound through the area’s full range of active motion to assess for the presence of foreign bodies. Irrigate with saline or tap water and be assured there is no significant difference in rates of infection between the two [9]. Consider using a finger tourniquet to achieve hemostasis of digital lacerations.

Local anesthesia such as lidocaine or bupivacaine with epinephrine (concentration up to 1:100,000) can help achieve hemostasis in a healthy individual (e.g., no history of peripheral vascular disease) without risk of digital necrosis. Local infiltration is typically more painful for the patient to endure as compared to a digital or nerve block. Using a smaller needle gauge, warming the anesthetic, mixing it with sodium bicarbonate, and slow injection can also help minimize discomfort [6, 10-11].

Refer to Dr. Hill’s prior TTS post on Regional Anesthesia for more information about local anesthetics and how to perform a digital, median, or radial nerve block.

Sutures such as the non-absorbable monofilaments Ethilon (nylon) or Prolene (polypropylene) usually in a 4-0 or 5-0 size are a standard choice for wound closure. Fast gut is a resorbable suture that does not require return for removal and is a great alternative in patients who may not have reliable follow-up. Be aware that when using fast gut while suturing over a joint line, it does not have the tensile strength of non-absorbable sutures and should be used with caution in those scenarios. Simple interrupted is a basic yet appropriate suturing technique for closure. Most hand lacerations do not require multi-layer closure unless there is necessary repair of an underlying structure (tendon, nerve etc.).

Wound Care

Prophylactic antimicrobial therapy in uncomplicated hand lacerations has long been a controversial topic. Data suggests there is no statistically significant difference in infection rates between antibiotic and placebo control groups. Applying a topical ointment (such as polymyxin or bacitracin) is sufficient for clean, uncomplicated lacerations in a healthy patient. A high degree of contamination, or a history of diabetes or immunocompromised state, should raise concern for risk of future infection and lower the threshold to provide prophylaxis. Cephalexin, clindamycin, and doxycycline are suitable choices to cover staph and strep skin flora and anaerobic bacteria, respectively [12-15].

Follow-up will be necessary if non-absorbable sutures are used; instruct the patient to present to their PCP or an ED in 10-14 days for removal. Sutures are left in place longer than other locations due to the hand’s higher degree of tension and mobility. Immobilizing splints may be utilized if the laceration is overlying a joint or the thumb.

Educate patients on warning signs and criteria for sooner wound evaluation, including fever and worsening pain, warmth, erythema, swelling or drainage from the wound. Scarring is inevitable, however applying vitamin E oil and sunscreen, as well as avoidance of prolonged sun exposure for up to 1 year can help achieve a more favorable cosmetic result.

Post by Nicole Bardakos

Nicole is an MS3 at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine

Peer Review and Editing by Bronwyn Finney, MD and Anita Goel, MD

Dr. Finney is a PGY-2 in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati

Dr. Goel is a faculty member in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati

References

Colen DL, Fox JP, Chang B, Lin IC. Burden of Hand Maladies in US Emergency Departments. Hand (N Y). 2018;13(2):228-236. doi:10.1177/1558944717695749

Jackson LL. Non-fatal occupational injuries and illnesses treated in hospital emergency departments in the United States. Injury Prevention. 2001; 7(Suppl I):i21-26

Sorock GS, Lombardi DA, Courtney TK, Cotnam JP, Mittleman MA. Epidemiology of occupational acute traumatic hand injuries: a literature review. Safety Science. 2001; 38(3):241-256.

Quinn JV, Polevoi SK, Kohn MA. Traumatic lacerations: what are the risks for infection and has the ‘golden period’ of laceration care disappeared? Emerg Med J. 2014;31(2):96–100.

Zehtabchi S, Tan A, Yadav K, Badawy A, Lucchesi M. The impact of wound age on the infection rate of simple lacerations repaired in the emergency department. Injury. 2012;43(11):1793–1798

Forsch RT, Little SH, Williams C. Laceration Repair: A practical approach. Am Fam Physician. 2017; 95(10):628-636.

Rockwell W., Bradford PN., Butler, Byrne BA. Extensor tendon: anatomy, injury, and reconstruction. Plastic and recons surg. 2000; 106(7):1592-603.

Perelman VS, Francis GJ, Rutledge T, Foote J, Martino F, Dranitsaris G. Sterile versus nonsterile gloves for repair of uncomplicated lacerations in the emergency department: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43(3):362–370.

Moscati RM, et al. A multicenter comparison of tap water versus sterile saline for wound irrigation. Acad Emerg Med. 2008; 14(5):404-409.

Ilicki, J. Safety of Epinephrine in digital nerve blocks: A literature review. J of Emerg. Med. 2015; 49(5):799-809.

Otterness K, J Singer A. Updates in emergency department laceration management. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2019; 6(2):97-105. doi:10.15441/ceem.18.018

Cummings P, Del Beccaro MA. Antibiotics to prevent infection of simple wounds: a meta-analysis of randomized studies. Am J Emerg Med. 1995;13(4):396-400. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(95)90122-1

Zehtabchi, S. The role of antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of infection in patients with simple hand lacerations. Ann Emerg Med. 2007; 49(5):682-689.

Whittaker JP, Nancarrow JD, Sterne GD. The role of antibiotic prophylaxis in clean incisesd hand injuries: A randomized placebo controlled double blind trial. J of Hand Surg. 2005; 30(2):162-167.

Berwald N., Khan F., Zehtabchi S. Antibiotic prophylaxis for ED patients with simple hand lacerations: a feasibility randomized controlled trial. Am J of Emerg Med. 2014; 32(7):768-771.

Havers FP, Moro PL, Hunter P, Hariri S, Bernstein H. Use of Tetanus Toxoid, Reduced Diphtheria Toxoid, and Acellular Pertussis Vaccines: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:77–83.

Talan DA, Abrahamian FM, et al. Tetanus immunity and physician compliance with tetanus prophylaxis practices among emergency department patients presenting with wounds. Annals of Emerg Med. 2004; 43(3):305-314.