A Fix for a Stinging Heart - Pericarditis Treatment in the ED

/Background

Pericarditis is inflammation of the pericardial sac. Classically, pericarditis presents with sharp and pleuritic chest pain which is relieved by sitting up and forward. Pericarditis has multiple etiologies, but is most commonly idiopathic, assumed to be viral, in developed countries (1). Treatment of pericarditis should be targeted to the underlying etiology if possible (1). For presumed viral, idiopathic causes, most patients are treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and colchicine (1).

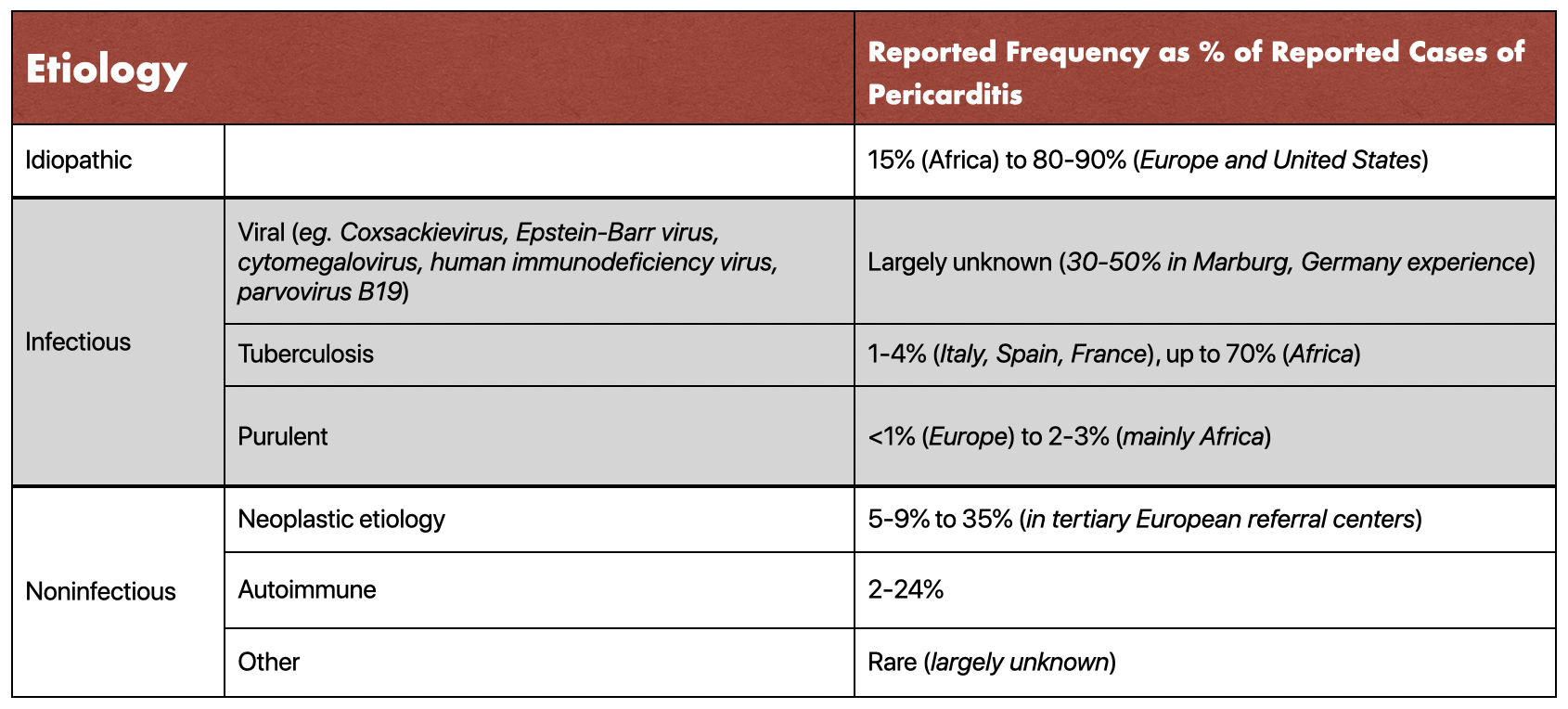

Etiology of Pericarditis. Recreated from Horneffer, Peter J., et al. “The Effective Treatment of Postpericardiotomy Syndrome after Cardiac Operations.”

NSAIDs

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are first line treatments for acute and recurrent pericarditis. Ibuprofen, aspirin, and indomethacin are the three top choices of NSAIDs. Research has focused on demonstrating efficacy and low adverse effects of NSAIDs rather than specific choice. There are no studies demonstrating significant changes of effectiveness between these choices of NSAIDs. However, aspirin is the NSAID of choice in pericarditis due to myocardial infarction or when patients’ require antithrombotic therapy.

A single double-blind randomized controlled trial of a 10 day course of ibuprofen or indomethacin versus placebo in 149 patients demonstrated effective treatment of postpericardiotomy syndrome with ibuprofen (90.2% effective) and indomethacin (88.7% effective) versus placebo (62.5% effective, p = 0.003) (1). Effective treatment was defined as resolution of at least 2 of fever, chest pain, and friction rub within 48 hours.

In a series of 254 patients, NSAIDs were 87% effective in treating acute pericarditis (2). In the aspirin-responsive cohort, 98% of patients were presumed to have viral or idiopathic causes while 2% were diagnosed with an autoimmune disorder. In contrast, of the aspirin-resistant cases, 43% were diagnosed with an autoimmune disorder, 18% with tuberculosis, and 39% were presumed viral or idiopathic. Moreover, aspirin-resistant cases had higher rates of recurrence and constrictive pericarditis (all p<0.01).

Research of postmyocardial infarction pericarditis identified two studies that demonstrated efficacy of aspirin and indomethacin in relieving symptoms of pericarditis within 48 hours (3).

Duration of treatment with NSAIDs typically follow patient symptoms. Research has shown that tapering of NSAIDs reduces risk of recurrence of pericarditis (2, 3). Tapering should be over 2-4 weeks starting after 24 hours of symptom resolution with or without CRP normalization. In a study of 200 patients with viral or idiopathic pericarditis, 78% of patients had an elevated high sensitivity CRP at diagnosis (4). High-sensitivity CRP normalized in 120 of 200 patients (60%) at week one, 170 of 200 patients (85%) at week two, 190 of 200 (95%) at week three, and all cases (100%) at week four. Patients with presence of elevated hs-CRP at week one had a higher recurrence rate of pericarditis (hazard ratio, 2.36; 95% confidence interval, 1.32 to 4.21; P = 0.004).

Moreover, failure of response (symptom improvement) after one week of NSAID treatment suggests a cause other than viral idiopathic. At this point, other causes of pericarditis should be analyzed and identified for more targeted treatment (4).

There is a theoretical bleeding risk with NSAIDs combined with other antithrombotics. However, no higher risk of hemorrhagic effusion or cardiac tamponade has been found. In a multivariable analysis of a prospective study of 453 patients demonstrated no increased risk of complications in patients with concurrent oral anticoagulant use (5). In a study of 274 cases of idiopathic or viral acute pericarditis, use of heparin or other anticoagulants was not associated with an increased risk of cardiac tamponade or recurrences (OR = 1.1, 95% CI 0.3 to 3.5; p = 0.918) (6).

Colchicine

Colchicine is an anti-mitotic drug, given as an adjunct to NSAIDs in treatment of pericarditis. Colchicine improves remission rates at one week, reduces recurrence rates, and reduces risk of treatment failure compared to NSAIDs alone.

The ICAP trial is a randomized, double-blind study of colchicine + anti-inflammatory treatment versus placebo + anti-inflammatory treatment. ICAP demonstrated a reduced risk of recurrence (17 % with colchicine versus 38% placebo, RRR 0.56, 95% CI 0.30-0.72) (7).

COPE is an open label trial of 120 patients who had a first episode of acute pericarditis. The recurrence rate within 18 months was lower in patients treated with colchicine plus aspirin (11%) versus aspirin alone (32%). The number needed to treat in order to prevent one additional patient from developing recurrent pericarditis in this trial was five (8).

Two 2014 systematic review and meta-analyses found reduced risk of recurrent pericarditis without significant increase in adverse events (i, j) One analyzed 4 randomized double-blind trials (564 patients) of colchicine for initial and recurrent episodes (9). A reduced risk of recurrent pericarditis at 18 months was found for acute pericarditis (HR 0.40, 95% CI 0.27-0.61) and recurrent pericarditis (HR 0.37, 95% CI 0.24-0.58). The pooled relative risk for adverse events was 1.26 (95% CI 0.75 to 2.12). The second systematic review and meta-analysis used seven controlled clinical trials (1275 patients) and resulted in similar findings (10). Meta-analysis showed colchicine use is associated with a reduced risk of recurrence (OR 0.33 (0.25-0.44)). The most frequent side effect was gastrointestinal intolerance (mean incidence 8%) but no serious adverse events were noted (OR 1.28 (0.84-1.93)).

Colchicine is available in the United States in 0.6 mg tablets. Colchicine should be administered for 3 months for the initial episode. A loading dose can be given at 0.6-1.2 mg twice on day one, but is not necessary according to the ICAP trial (7). The maintenance dose is weight based with 0.6 mg twice a day for patients greater than 70 kg, and 0.6 mg daily for patients weighing less than 70 kg.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are used in pericarditis treatment when a patient has a contraindication to NSAIDs or in cases of systemic inflammatory disease, pregnancy, and renal failure. Corticosteroids can also be used in cases of recurrent or refractory pericarditis when NSAID plus colchicine use has failed. However, steroids are associated with more adverse effects and higher recurrence rates in non-randomized studies.

Patients in the COPE trial were given steroids when aspirin was contraindicated or not tolerated (7). Use of steroids was an independent risk factor for developing recurrences of pericarditis with an odds ratio of 4.30, 95% CI 1.21-15.25.

A systematic review including two randomized trials of steroid therapy versus NSAIDs and one trial of low versus high dose steroid therapy showed a higher rate of recurrent pericarditis (11). Low-dose steroids proved superior to high-dose steroids for treatment failure or recurrent pericarditis (OR = 0.29 (0.13-0.66)), rehospitalizations (OR = 0.19 (0.06-0.63)), and adverse effects (OR = 0.07 (0.01-0.54)).

Therefore, moderate initial dosing of prednisone (0.2-0.5 mg/kg/day) followed by a slow taper is generally preferred. Start the taper 2-4 weeks after symptom resolution and CRP normalization and stop taper if symptoms return or CRP elevates.

Surgical treatments

In rare cases, surgical treatment of pericarditis has been attempted. In a retrospective series from Mayo Clinic of 184 patients, there were fewer relapses of chronic pericarditis in patients with pericardiectomy than in patients who received medical therapy (p=0.009) (12). However, there was no difference in all-cause death at follow-up (p=0.26). According to the European Society of Cardiology, pericardiectomy should be reserved for cases of constrictive pericarditis or in some patients with relapsing pericarditis (13).

Recommendations

In initial cases of acute pericarditis, patients should be treated with an NSAID plus colchicine. Corticosteroids should be used when a patient has a contraindication to NSAIDs or in cases of systemic inflammatory disease, pregnancy, and renal failure. Corticosteroids can also be used if NSAID plus colchicine treatment has failed (no resolution of symptoms in 1 week). Patients with constrictive pericarditis and rarely patients with relapsing pericarditis can be treated with pericardiectomy.

Resources

Authorship

Written by Elizabeth Stevens, MD, MA, PGY-1 University of Cincinnati Department of Emergency Medicine

Editing and Posting by Jeffery Hill, MD MEd