Annals of B Pod - Ovarian Torsion

/HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS

The patient is a G1P1001 female in her 20s who presents to the emergency department (ED) with a several-week history of right-sided flank pain with radiation to the suprapubic region. She describes the pain as intermittent and crampy. Over the past one-to-two days, the pain has acutely worsened and is now associated with multiple episodes of non-bloody, nonbilious emesis. Her last menstrual period was approximately one month ago. She is not currently sexually active and does not use contraceptives. Five days prior to presentation, she was seen in another facility where a urinalysis was notable for hematuria and she had a negative beta-hCG. No imaging was completed at that time, and she was diagnosed with presumptive nephrolithiasis and treated with naproxen, tamsulosin, and tramadol. She reports her pain has acutely worsened despite adherence to the above therapies. She denies any associated chest pain, shortness of breath, fever, chills, vaginal discharge, vaginal bleeding, diarrhea, or constipation.

Past medical history: None

Past surgical history: None

Medications: Naproxen, Tamsulosin, Tramadol

Allergies: No known allergies

PHYSICAL EXAM

Vitals: T 36.7 HR 71 BP 122/71 RR 14 SpO2 100% on RA

The patient is a young Hispanic female who appears uncomfortable but in no acute distress. She is well-developed with no evidence of external trauma. Her abdomen is soft, non-distended with marked tenderness to palpation in the right flank and suprapubic regions. Psoas and obturator tests are negative, and she has no McBurney point tenderness to palpation. She has normoactive bowel sounds. Cardiac, pulmonary, and neurologic exams are normal. Musculoskeletal and skin exam demonstrate appropriate range of motion and no rashes, ecchymosis, or lesions.

Diagnostics

WBC: 16 Hgb: 14.3 Hct: 45.1 Plt: 169

Na: 146 K: 4.4 Cl: 117 HCO3: 10 BUN: 16 Cr: 1.2 Glucose: 223

Urine hCG: negative

UA: blood trace, protein trace, nitrite negative, leukocyte esterase negative

Hospital course

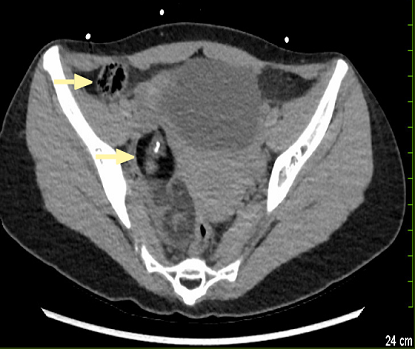

The patient was given ondansetron, morphine, and ketorolac for symptom control. Differential diagnosis included ectopic pregnancy, ruptured ovarian cyst, tubo-ovarian abscess, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion, uterine leiomyoma, urinary tract infection, nephrolithiasis, pyelonephritis, and appendicitis, among others. The providers obtained cross-sectional imaging, which revealed an intraabdominal mass suggestive of a possible ovarian teratoma. Gynecology was emergently involved given the patient’s persistent pain and concern for torsion of the right adnexa. The patient had an uncomplicated surgical resection of a large germ cell tumor as well as a right salpingo-oophorectomy and removal of a large ovarian cyst on hospital day one. She tolerated the procedure well and was discharged that same day. The patient has since followed up with gynecology and has noted no significant changes in her health related to this procedure. Pathology showed no evidence of malignancy. The two resected masses were confirmed as a mature cystic teratoma and serous cystadenoma.

Ovarian torsion

Pathophysiology

Ovarian torsion is a feared and difficult to diagnose emergency due to its relatively nonspecific presenting symptoms. [1] Ovarian torsion is the partial or complete rotation of the ovary on the axis between the utero-ovarian and infundibulopelvic ligaments. Often, both the ovary and fallopian tube are involved in this process, though isolated torsion of either structure individually may occur. Initially, ovarian torsion causes venous and lymphatic obstruction, which can then progress to congestion, edema, and eventually ischemia and necrosis if not surgically addressed. Complete arterial obstruction is rare due to the ovaries’ dual blood supply from the uterine and ovarian arteries. Additional sequelae from missed or advanced torsion besides damage to the ovary itself include intraperitoneal hemorrhage or infection with development of peritonitis.

Torsion can occur in females of all ages, but it is most common during the reproductive years due to the increased frequency of functional cysts and physiologic changes that occur during the menstrual cycle and pregnancy. The vast majority of torsion is thought to be induced by an ovarian mass, with only ten percent of cases estimated to occur in patients with ovaries without masses. [1,2] Most masses which cause torsion are benign in nature. Malignant neoplasms, by contrast, are often fixed in place by local adhesions and less likely to torse as a result. [3-6] A significant, but lesser-known, risk factor for torsion is pregnancy, which accounts for at least ten percent of all torsion cases. [1,2] This most often occurs in patients with a preexisting ovarian cyst during the second trimester of pregnancy. [7] Additional predisposing characteristics include recent infertility treatment, which can cause ovulation induction and hyperstimulation syndrome or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Finally, studies show that more than 80% of ovarian torsion cases had an ovarian mass greater than 5cm in diameter, and that torsion is more common on the right as opposed to the left, where the ovary tends to be comparatively confined due to the sigmoid colon and a shorter utero-ovarian ligament. [8,9]

Clinical Presentation

Classically, patients with ovarian torsion will report acute onset of severe, sharp, unilateral lower abdominal pain with associated nausea. However, as with many intraabdominal pathologies, these symptoms are relatively nonspecific and therefore require a high index of suspicion to ensure that the appropriate diagnostic studies are obtained. [5,6,10] Most patients will present within one to three days of symptom onset and may report a history of recent strenuous or vigorous activity. The younger the patient, the longer the symptoms are likely to occur prior to presentation, most likely due to intermittent torsion. [11,13] Known risk factors and a palpable adnexal mass should trigger providers to consider the diagnosis. [6] The differential diagnosis for acute lower abdominal pain in women includes gynecological, gastrointestinal and genitourinary, as mentioned above. However, unlike the other gynecologic and obstetric pathologies listed, vaginal discharge and bleeding is not common in ovarian torsion, thus this diagnosis can oftentimes be overlooked.

Diagnosis

A high index of suspicion is the greatest contributing factor in making the appropriate diagnosis of ovarian torsion. Laboratory evaluation is not often helpful apart from diagnosing pregnancy. Leukocytosis is uncommon unless the ovary has already become necrotic, thus a normal white blood cell count may increase suspicion for ovarian torsion over appendicitis, [13] however this is not reliable. Instead, one must rely on imaging to identify possible pathology. While CT and MRI can identify the presence of ovarian cysts or masses, and may suggest torsion through visualization of contrast impedance, ovarian edema, or fallopian tube thickening, ultrasound with doppler is considered the test of choice. [14] Both transvaginal and transabdominal studies are recommended in the evaluation of acute pelvic pathology. While most emergency departments still require consultative ultrasonography for formal diagnosis of ovarian pathologies, it is important to note what might be seen on point-of-care ultrasound to raise your clinical suspicion. [15,16] Asymmetric enlargement of the ovary is the most common finding. Classically, ultrasound will reveal an enlarged ovary with heterogenous stroma and small, peripherally displaced follicles, but these findings are often absent, especially with long standing ischemia. Ultrasound may also demonstrate evidence of ovarian masses, hemorrhage, or pelvic free fluid. Doppler ultrasound findings are inconsistent depending on time of evaluation, as torsion can occur intermittently. The most specific ultrasound finding is decreased or absent arterial doppler flow to the ovaries, which has between 92-97% specificity and a 94-100% positive predictive value for torsion. The whirlpool sign refers to visualization of a twisted pedicle and coiled vessels and also has a 90% positive predictive value for torsion. Ultrasound becomes increasingly sensitive and specific when there are at least two or more sonographic findings present. [13,17-20]

While confirmation of torsion on imaging is valuable in the clinical setting, it is critically important to maintain focus on the patient’s symptomology. Even in the absence of ultrasonographic signs of torsion, if ovarian torsion remains the leading diagnosis based on equivocal lab testing and imaging, there is still a role for emergent gynecologic consultation and laparoscopic evaluation if deemed necessary. Diagnostic laparoscopy remains the gold standard for patients in whom clinical suspicion remains high despite negative imaging results.

Treatment

Once ovarian torsion has been diagnosed, gynecology consultation is paramount. All torsed ovaries require urgent de-torsion and assessment of viability. This can only be accomplished by direct visualization in an operating suite and therefore the mainstays of emergency management are pain control and coordination of gynecologic or surgical evaluation. There is no definitive window after which an ovary is guaranteed to be non-viable, however some studies quote better outcomes if identified and treated within eight hours. [21] Thus, timely identification and involvement of consulting services is of the essence.

summary

Ovarian torsion remains a highly morbid disease process that is difficult to diagnose. Emergency physicians need to have a high clinical suspicion of ovarian torsion in women of reproductive age. Appropriate use of imaging will lead to an expedited diagnosis and subsequently decrease the risk of infectious and fertility complications.

AUTHORED BY Olivia Urbanowicz, MD

Editing BY the Annals of B Pod Editors

References

Sanfilippo JS, Rock JA. Surgery for benign disease of the ovary. In: TeLinde's Operative Gynecology, 11th ed., Jones HW, Rock JA (Eds), Wolters Kluwer, 2015.

Pelvic Mass. In: Hoffman BL, Schorge JO, Bradshaw KD, Halvorson LM, Schaffer JI, Corton MM. eds. Williams Gynecology, 3e New York, NY: McGraw- Hill. http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=1758§ionid=118168387. Accessed July 06, 2019.

Varras M, Tsikini A, Polyzos D, et al. Uterine adnexal torsion: pathologic and gray-scale ultrasonographic findings. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 2004; 31:34.

Oltmann SC, Fischer A, Barber R, et al. Cannot exclude torsion--a 15-year review. J Pediatr Surg 2009; 44:1212.

Pansky M, Smorgick N, Herman A, et al. Torsion of normal adnexa in postmenarchal women and risk of recurrence. Obstet Gynecol 2007; 109:355.

Houry D, Abbott JT. Ovarian torsion: a fifteen-year review. Ann Emerg Med 2001; 38:156.

Yen CF, Lin SL, Murk W, et al. Risk analysis of torsion and malignancy for adnexal masses during pregnancy. Fertil Steril 2009; 91:1895.

Huchon C, Fauconnier A. Adnexal torsion: a literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2010; 150:8.

White M, Stella J. Ovarian torsion: 10-year perspective. Emerg Med Australas 2005; 17:231.

Huchon C, Panel P, Kayem G, et al. Does this woman have adnexal torsion? Hum Reprod 2012; 27:2359

.Rousseau V, Massicot R, Darwish AA, et al. Emergency management and conservative surgery of ovarian torsion in children: a report of 40 cases. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2008; 21:201.

Rossi BV, Ference EH, Zurakowski D, et al. The clinical presentation and surgical management of adnexal torsion in the pediatric and adolescent population. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2012; 25:109.

Pour, TR and Tibbles CD. (2018). Selected Gynecologic Disorders In R.M. Walls (Ed.), Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, 9th edition (pp. 1232-1239). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

Wilkinson C, Sanderson A. Adnexal torsion -- a multimodality imaging review. Clin Radiol 2012; 67:476.

Lee EJ, Kwon HC, Joo HJ, et al. Diagnosis of ovarian torsion with color Doppler sonography: depiction of twisted vascular pedicle. J Ultrasound Med 1998; 17:83.

Nizar K, Deutsch M, Filmer S, et al. Doppler studies of the ovarian venous blood flow in the diagnosis of adnexal torsion. J Clin Ultrasound 2009; 37:436.

Bar-On S, Mashiach R, Stockheim D, et al. Emergency laparoscopy for suspected ovarian torsion: are we too hasty to operate? Fertil Steril 2010; 93:2012.

Valsky DV, Esh-Broder E, Cohen SM, et al. Added value of the gray-scale whirlpool sign in the diagnosis of adnexal torsion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010; 36:630.

Vijayaraghavan SB, Senthil S. Isolated torsion of the fallopian tube: the sonographic whirlpool sign. J Ultrasound Med 2009; 28:657.

Mashiach R, Melamed N, Gilad N, et al. Sonographic diagnosis of ovarian torsion: accuracy and predictive factors. J Ultrasound Med 2011; 30:1205.

Yancey L. Ovarian torsion. https://www.saem.org/cdem/education/online-education/m4-curriculum/group-m4-genitourinary/ovarian-torsion. Accessed 12/28, 2019.